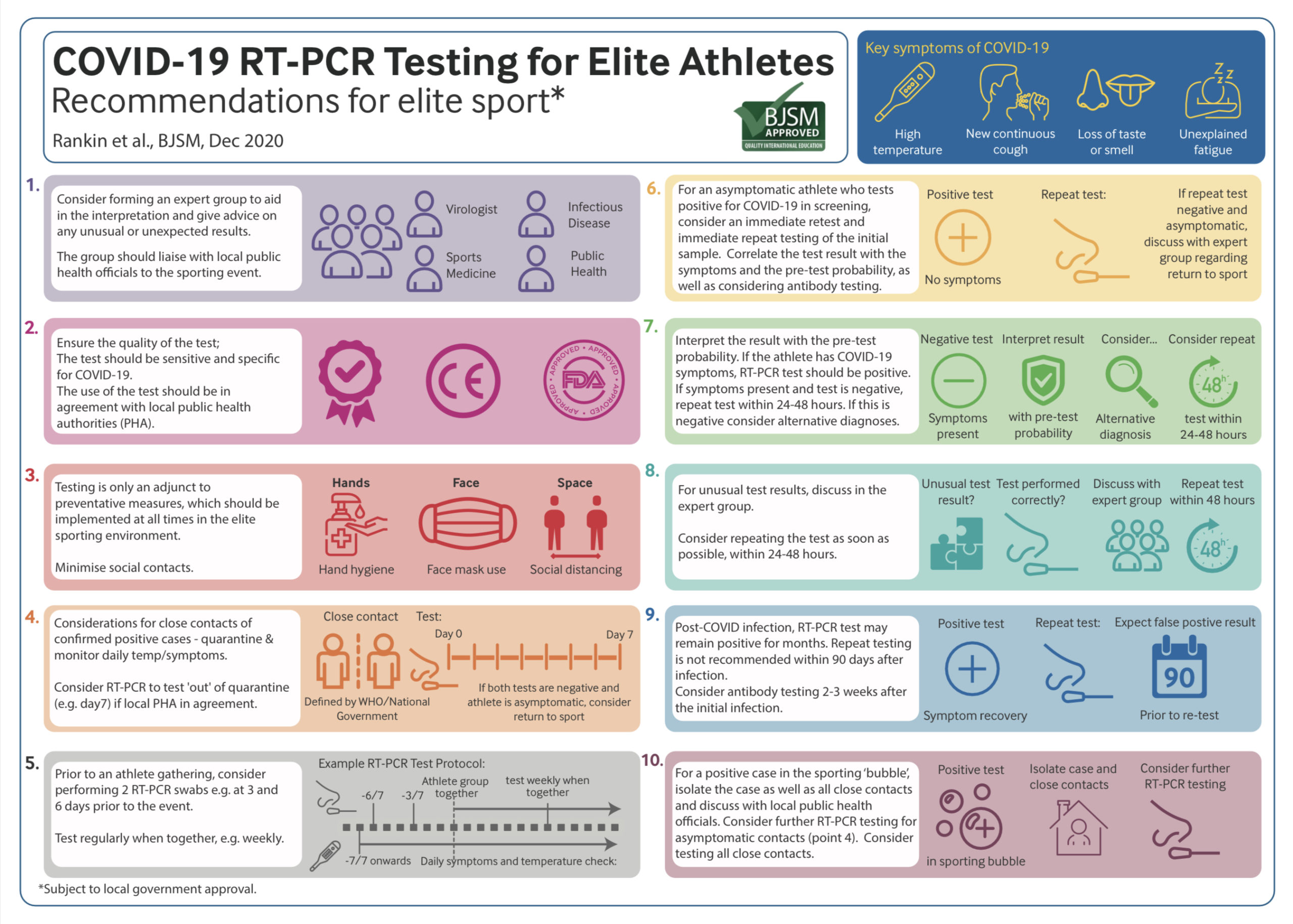

This infographic outlines evidence-based recommendations on COVID-19 reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing in elite sport settings, aiming to protect personal and population health, and acknowledging resources and expertise that are often available in elite sport. Public health recommendations vary by country and region and protocol decisions should be made in consultation with relevant public health authorities.

Form an expert group

An expert, multidisciplinary group with input from clinical virology, microbiology, public health, infectious diseases and sports medicine provides optimal implementation and interpretation of testing

Prevention is best

Interventions to prevent COVID-19 transmission should be implemented consistently (1,2) and include:

- Effective hand hygiene.

- Physical distancing: athletes should minimise discretionary social contacts and maintain a distance of at least one metre from others.

- Wearing a mask at all times when around others, especially indoors.

- Prioritising outdoor over indoor activity where possible.

COVID-19 and RT-PCR testing

The current gold standard of testing is RT-PCR testing (4-6). The test is highly sensitive and specific to SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA in laboratory conditions (2). Test results should be interpretated on the basis of the pre-test probability, previous test results and clinical history. Test sensitivity and specificity will rely on the: i) quality and location of swabbing; ii) testing equipment and reagents; and, iii) laboratory expertise.

Close contacts (7) to a positive-testing athlete should be isolated and proceed with daily monitoring for symptoms and temperature, and where available testing. If the contact is asymptomatic and COVID-19 RT-PCR tests are negative at 7 day follow-up, the close contact could be considered for a return to sport, depending on discussions with local public health authorities.

Testing and Elite Athlete Gatherings

Prior to a gathering of elite athletes, for example at a training camp or competition, all athletes should have regular symptom checks and undergo RT-PCR or other screening for the virus. For the first gathering, testing 6 and 3 days prior to the event is recommended, as well as testing as close to the event as logistically possible. Interval (for example weekly) PCR testing for the duration of the gathering should be considered.

Managing a Positive Test

Positive tests should be managed according to national and local public health guidance, but elite sport can often provide additional medical and testing support. The positive case, as well as all close contacts, should be isolated as soon as possible, and contact tracing undertaken.

If an asymptomatic athlete tests positive in screening, they should be isolated but retested to ascertain whether the result represents a true or false positive. False positives are less likely when the prevalence of COVID-19 is high. In a symptomatic individual, a positive result is considered a true positive. Careful attention should be paid to the PCR cycle threshold (Ct) and the gene expression of the result, as this correlates strongly with cultivable virus.(4) A test with a high Ct (>30, and especially >35) may not indicate current infectivity (4, 5), although the viral load may rise in subsequent days.

Interpreting a Negative Test in an Athlete

If an athlete has symptoms indicative of coronavirus (e.g., loss of taste/smell, dry cough, pyrexia) but test results are negative, repeat testing is recommended to exclude a false negative, especially if there is a high prevalence of COVID-19 activity. An alternative diagnosis with testing for other viral aetiologies should also be considered. Unusual test results should be discussed within the expert group.

Re-testing Post-COVID infection

Viral RNA can persist in individuals beyond infectivity for several months (4-6). For this reason, repeat PCR screening in asymptomatic athletes is not routinely recommended for 90 days post-infection. Repeat testing can stratify whether viral load is decreasing and may inform decisions to isolate a patient beyond 10 days in some cases. In the event an athlete has been retested within 90 days, consider their Ct value. When Ct>35 and the patient’s symptoms have resolved, infectivity is unlikely (6).

Return to sport for a COVID-19 confirmed case

Following infection, there should be a graduated return to sport, guided by professional advice which may vary based on the severity of the illness, the demands of the sport and logistical factors (8)(9)(10).

Authors & Affiliations:

Rankin, A1; Massey, A2; Falvey, E3; Ellenbecker, T4; Harcourt, P 5,6; Murray, A 7,8; Kinane, D9; Niesters H10; Jones, N11; Martin, R12; Roshon, M13; McLarnon, M14; Calder, J15; Izquierdo, D7; Pluim, BM 16,17,18; Elliot, N19; Heron, N 1,14,20.

- Sports Institute Northern Ireland, Sports Medicine;

- Medical Department, FIFA (Federation Internationale de Football Association).

- Medical Department, World Rugby.

- Medical department. Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) Tour. Ponta Vedra Beach. Florida. USA.

- Medical and Scientific department. International Cricket Council.

- Medical and Scientific department. Australian Football League.

- Medical and Scientific Department. European Tour Golf. Various. Virginia Water. UK. GU25 4 LX.

- Centre for Sport and Exercise. University of Edinburgh. 46 Pleasance. Edinburgh. UK. EH8 9TJ.

- Immunology Department. University of Berne. Switzerland.

- The University of Groningen, University Medical Center Groningen, Department of Medical Microbiology, Division of Clinical Virology, Groningen, The Netherlands.

- Medical Department, British Cycling, Manchester.

- Welsh Institute of Sport, Sport Wales, Cardiff.

- Medical Department, USA Cycling.

- Centre for Public Health, Queen’s University Belfast.

- Fortius Clinic, London, UK.

- Section Sports Medicine, University of Pretoria, Faculty of Health Sciences, Pretoria, South Africa

- Amsterdam Collaboration on Health and Safety in Sports (ACHSS), AMC/VUmc, IOC Research Center of Excellence, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Medical Dept., Royal Netherlands Lawn Tennis Association (KNLTB), Amstelveen, The Netherlands

- Medical Department, Scottish Institute of Sport, Scotland.

- School of Medicine, Keele University, Staffordshire, England.

References:

- Toresdahl BG, Asif IM. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Considerations for the Competitive Athlete. Sports Health. 2020;12(3):221-4.

- Watson J, Whiting PF, Brush JE. Interpreting a covid-19 test result. BMJ. 2020;369:m1808.

- Eikenberry SE, Mancuso M, Iboi E, Phan T, Eikenberry K, Kuang Y, Kostelich E, Gumel AB. To mask or not to mask: Modeling the potential for face mask use by the general public to curtail the COVID-19 pandemic. Infectious Disease Modelling. 2020 Apr 21.

- Singanayagam A, Patel M, Charlett A, Lopez Bernal J, Saliba V, Ellis J, et al. Duration of infectiousness and correlation with RT-PCR cycle threshold values in cases of COVID-19, England, January to May 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(32):2001483.

- Group SRA. Interpretation of PCR Results and Infectivity2020 30/06/2020. Available from: https://covid-19.sciensano.be/sites/default/files/Covid19/30300630_Advice_RAG_interpretation%20PCR.pdf.

- Bullard J, Dust K, Funk D, Strong JE, Alexander D, Garnett L, et al. Predicting Infectious Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 From Diagnostic Samples. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020.

- United Kingdom government. Website: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-for-contacts-of-people-with-possible-or-confirmed-coronavirus-covid-19-infection-who-do-not-live-with-the-person/guidance-for-contacts-of-people-with-possible-or-confirmed-coronavirus-covid-19-infection-who-do-not-live-with-the-person. Accessed on 30/10/2020.

- Elliott N, Martin R, Heron N, Elliott J, Grimstead D, Biswas A. Infographic. Graduated return to play guidance following COVID-19 infection. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2020;54(19):1174-5.

- Carmody S, Murray A, Borodina M, Gouttebarge V, Massey A. When can professional sport recommence safely during the COVID-19 pandemic? Risk assessment and factors to consider. British Journal of Sport and Exercise Medicine (BJSM). 2020 Aug;54(16):946-948. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-102539.

- Löllgen H, Bachl N, Papadopoulou T, et al. Recommendations for return to sport during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine 2020;6:e000858. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000858

- Baggish, A; Drezner, JA; Kim, J;Martinez, M; Prutkin, JM. Resurgence of sport in the wake of COVID-19: cardiac considerations in competitive athletes. British Journal of Sport and Exercise Medicine. 2020;54:1130-1131.