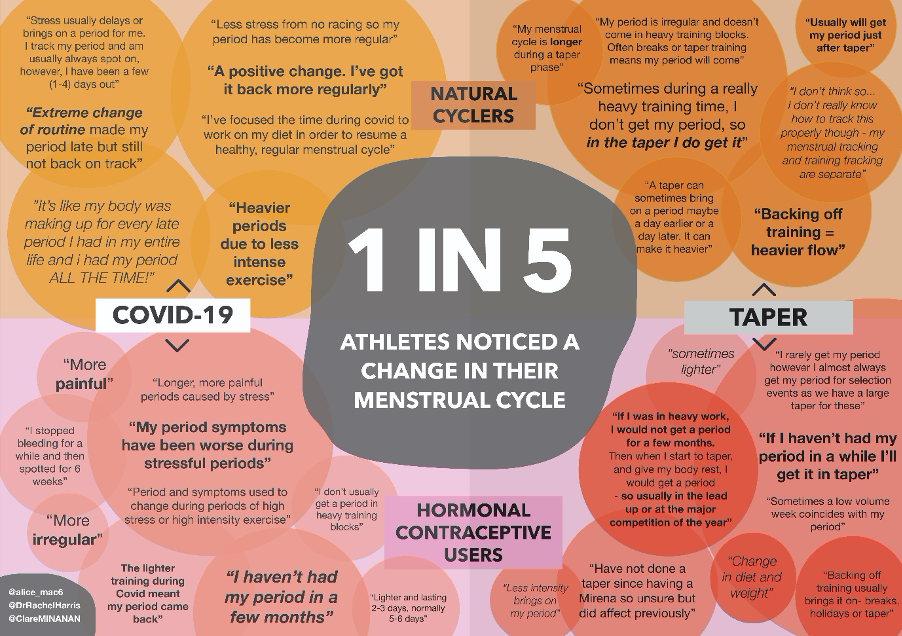

One in five elite female Australian athletes in Olympic and Paralympic sports preparing for Tokyo 2021, have experienced a change in their menstrual cycle during COVID-19.

The Australian Institute of Sport Female Performance & Health Initiative initiated research surrounding elite athlete perceptions and experience of the menstrual cycle on performance. This research surveyed Australian Tokyo-potential athletes from April 2020, regarding their menstrual cycle symptomatology, hormonal contraceptive use, cycle tracking, management, and the perceived effect of the menstrual cycle on performance. Respondents were divided into streams; those taking hormonal contraception, and those who are naturally cycling. Overall survey results will be published later, however with the relevancy of COVID-19 on athlete management in 2020, we wished to discuss some early results.

The global pandemic of COVID-19 has rocked the sports world, causing the cancellation of events, postponement of the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic games, and disruption of athlete schedules. Our hypothesis is that a global pandemic will have both physiological and psychological impacts on our athletes and their experience of their individual menstrual cycle.

The menstrual cycle is controlled by the hypothalamic–pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis by positive and negative feedback mechanisms between hypothalamus, anterior pituitary, and the ovaries. The HPO is well known to be affected by common stressors including inadequate fuelling strategies, psychological stressors, or significant alterations to physical stress, travel, and insufficient sleep1,2,7.

Current evidence supports that energy availability is crucial to GnRH pulsatility at the hypothalamus, altering LH and FSH release from the pituitary and decreased estrogen and progesterone levels2. Athletes, with high training volumes can experience a relative energy deficiency at different times of their preparation2. In a taper, it is usual to see a reduction in training volume with similar or unchanged energy intake that can alter or correct an energy deficit2. The magnitude of an energy deficit can cause disturbance in menstrual function (including luteal phase defects, anovulation and oligomenorrhoea), and equally a correction can restore it2.

We also hypothesised there was likely to be a psychological impact of the global pandemic and postponement of major competition. For athletes, change may mean uncertainty about sporting and career goals, identity as an athlete and like everyone, fear and anxiety about the disease and loneliness due to social isolation3 The relationship between stress and menstrual cycle characteristics may vary from individual to individual. Several studies4,5 have found that self-reported measures of stress correlate with longer menstrual cycles. In contrast, other studies have found women who reported that their employment was characterized by high stress, but had low control over their work environment, had a higher risk of short cycles6. This lack of control may affect athletes intermittently throughout COVID-19.

We asked survey respondents, “Has your menstrual cycle been affected by a change in routine or stress during COVID-19?” and, “Does a taper phase normally change your menstrual cycle?”

We found that 19.6% of hormonal contraceptive users and 24.7% of natural cyclers, or one in five athletes, experienced a change in their menstrual cycle during COVID-19 lockdowns.

For comparison, 12.5% of hormonal contraceptive users and 18.5% of natural cyclers noticed menstrual cycle change during a normal taper phase.

One fifth of female athletes have experienced a change in their menstrual cycle during COVID-19. We hypothesize there may be several reasons behind these observations, both physiological and psychological. There may be a physiological change as a result of load reduction and relative taper, But, the study did not quantify training load throughout COVID-19 period, and therefore we cannot be sure that athletes were or were not tapering unless they commented so. We know that for some sports, like cycling, training volumes could continue, on online platforms. We hypothesize that a psychological component is also relevant. When we work with athletes in these unprecedented times, promoting awareness of their individual menstrual cycle and changes, energy levels and symptoms may provide useful performance and wellbeing information.

Authors and Affiliations:

Dr Alice McNamara OLY BComm BSCi MD EMCert (ACEM)

ACSEP Sports Medicine Registrar – MP Sports Physicians Melbourne

Pathways Medical Officer Rowing Australia

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3046-4223

Dr Rachel Harris OLY MBBS FACSEP IOCDipSpPhy

Sport and Exercise Medicine Physician

Australian Institute of Sport, Female Performance Initiative – Project Lead

Chief Medical Officer Paralympics Australia; Chief Medical Officer Water Polo Australia

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1955-894X

A/Prof Clare Minahan, PhD Associate Professor, AES ASpS2 ASCA2 Griffith Sports Science, Griffith University, Australia

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1955-894X

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References:

- Mujika I Padilla S, Pyne D, Busso T (2004) Physiological Changes Associated with the Pre-Event Taper in Athletes; Sports Med 2004; 34 (13): 891-927.

- Mountjoy M, Sundgot-Borgen JK, Burke LM et al; IOC consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update, International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism; doi: 10.1123/IJSNEM.2018-0136

- Edwards C and Thornton, J (2020); Athlete mental health and mental illness in the era of COVID-19: shifting focus with a new reality BJSM Blog https://blogs.bmj.com/bjsm/2020/03/25/athlete-mental-health-and-mental-illness-in-the-era-of-COVID-19-shifting-focus-a-new-reality/ March 25, 2020

- Matteo S. The effect of job stress and job interdependency on menstrual cycle length, regularity and synchrony. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1987;12(6):467–476

- Harlow SD, Matanoski GM. The association between weight, physical activity, and stress and variation in the length of the menstrual cycle. Am J Epidemiol 1991;133(1):38–49.

- Fenster L, Waller K, Chen J, Hubbard AE, Windham GC, Elkin E, et al. Psychological stress in the workplace and menstrual function. Am J Epidemiol 1999;149(2):127–134.

- Bruinvels G, Lewis N, Blagrove R, Scott D, Simpson R, Baggish AL, Rogers JP, Ackerman K, Pedlar CR, COVID-19 – Considerations for the female athlete (in press)