Part of a new MSK-focused blog series

Lateral hip pain is a common complaint in our active patient population. It has certainly become more prevalent during and after ‘lockdown’ as patients shift towards different exercise modalities or cease being physically active, leading to ‘stress shielding’ of tendons.

Gluteal tendinopathy is the most prevalent pathology at the lateral hip (often incorrectly attributed to trochanteric bursitis)1. It is the typical culprit in an older female walking, hiking and jogging demographic, but it is important to be aware of other causes of pain in this region, especially where symptoms localise more superiorly at the iliac crest. If a runner develops functionally disabling impact related pain at this level then tensor fascia lata (TFL) origin enthesopathy2 (or ‘proximal iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome3) should be suspected.

Anatomy and pathobiomechanics

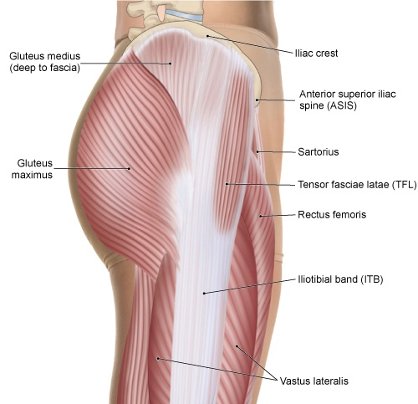

The TFL originates from the anterior portion of the iliac crest (tubercle), just posterior to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). Proximally around the lateral hip, the ITB (a specialised portion of the lateral thigh fascia), blends in a complex fashion with the TFL and the gluteal myoaponeurotic tissues4.

Together, the TFL and ITB have important functional roles5 including facilitating active hip movement (abduction, flexion and rotation). In a sporting context, they assist in stabilising the lumbopelvis and trunk via complex insertions inferiorly in the thigh and at the knee level, providing postural support during one legged stance and running, as well as reducing femoral torsion.

The TFL works harder and is prone to injury when there is a global strength and control deficit around the hip, or simply with over-training. With repetitive tractional overload, chronic microtrauma occurs at the TFL and ITB origin bone-fascia interface leading to enthesopathy.

LATERAL VIEW OF THE PELVIS AND THIGH. PERMISSION JOSEPH E. MUSCOLINO. THE MUSCULAR SYSTEM MANUAL – THE SKELETAL MUSCLES OF THE HUMAN BODY, 4ED, ELSEVIER, 2017.

Examination

The patient is typically point tender over a distance of 1-2cm along the iliac tubercle (see picture). This is the epicentre, but the pain can be perceived radiating more diffusely over the lateral gluteal area towards the greater trochanter.

Without careful systematic palpation, the focal area of pain can be missed; patients can find it hard to localise the pain as well, often being surprised when the clinician finally hits the sore spot.

Symptoms can be provoked on resisted hip testing on the bed, but often pain is more reliably reproduced on higher impact functional testing eg hopping drills or on the treadmill.

Imaging

MRI scanning can delineate the injury if florid with bone marrow oedema, increased soft tissue signal intensity on T2 (fluid sensitive) sequences and thickening of the proximal attachment2; but MRI may miss the injury given the small area it affects.

We feel ultrasound is the modality of choice not least because the patient can localise the pain and it can be evaluated with precision at the point of care.

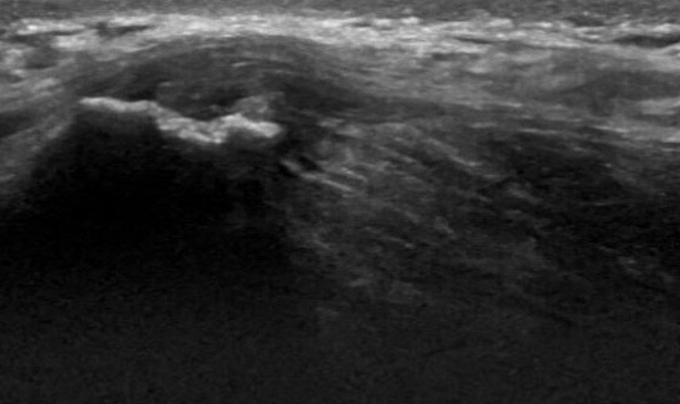

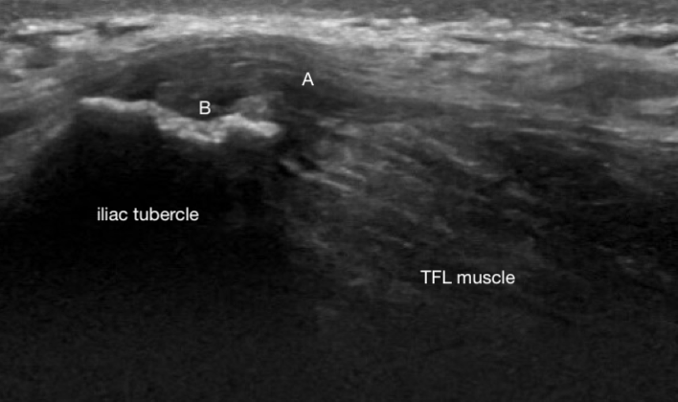

Typical sonographic features6 include a thickened, heterogenous hypoechoic enthesis (Fig 1 – A); cortical irregularity at the origin insertion (Fig 2 – B); enthesophytes (spurs) and calcific foci of variable size. US also permits concurrent assessment of the gluteal tendon and potential bursal inflammation.

Ultrasound – longitudinal scan of TFL origin at iliac crest (Noake)

Differential diagnoses

- History of trauma or acute onset? Consider a tear of the TFL muscle or ITB fascial origin

- In adolescents

- Apophyseal avulsion fracture

- Traction apophysitis if an ‘overuse’ picture in a younger teen

- Iliac tumour

- Iliohypogastric nerve irritation

- In the absence of palpable tenderness, consider referred pain from the lumbar spine, sacroiliac joint or hip joint.

Treatment

TFL enthesopathy can be a challenging condition to manage in terms of restoring pain free running function; recovery times are comparable to and management principles mirror those of gluteal tendinopathy.

Treatment is non-surgical and focused on load management and lumbopelvic rehabilitation, addressing key strength and neuromuscular control deficits, building tolerance in the irritable structures.

It is important to be realistic about return-to-running timescales (6-12 months plus in stubborn cases) with patients so that they remain motivated and keep faith in the rehabilitation process.

Safe pain modulating options include shockwave therapy or GTN patches. In recalcitrant cases, an ultrasound-guided cortisone injection may be considered although risks including fat atrophy and skin hypopigmentation should be discussed with the patient.

Conclusion

- Fascial overuse injuries are frequently misdiagnosed and patients can end up being inappropriately treated for hip joint or gluteal tendon related conditions

- Careful palpation of the iliac crest and POCUS are key in diagnosis

Authors and Affiliations:

Dr James Noake. Consultant in Sport and Exercise Medicine. Pure Sports Medicine. Consultant to London Irish RFC

Dr Lorenzo Masci. Consultant in Sport and Exercise Medicine. Consultant in Sports and Exercise Medicine with an interest in tendons, diagnostic ultrasound and ultrasound-guided interventions

Dr Carles Pedret. Sports Medicine and Sports Orthopedics MD, PhD.

References:

- Gluteal Tendinopathy: A review of mechanisms, assessment and management Grimaldi, Alison. , Mellor, Rebecca. , Hodges, Paul. , Bennell, Kim, Wajswelner, Henry. Vicenzino, Bill.

- Huang BK, Campos JC, Michael Peschka PG, Pretterklieber ML, Skaf AY, Chung CB, et al. Injury of the gluteal aponeurotic fascia and proximal iliotibial band: anatomy, pathologic conditions, and MR imaging. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2013;33(5):1437-52. m

- Sher I, Umans H, Downie SA, Tobin K, Arora R, Olson TR. Proximal iliotibial band syndrome: what is it and where is it? Skeletal radiology. 2011;40(12):1553-6.

- A review of the anatomy of the hip abductor muscles, gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fascia lata, Flack et al. Clin Anat 2012 Sep;25(6):697-708.

- Which Exercises Target the Gluteal Muscles While Minimizing Activation of the Tensor Fascia Lata? Electromyographic Assessment Using Fine-Wire Electrodes. David M. Selkowitz et al. Journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2013. 43(2); 54-65

- Bass CJ, Connell DA. Sonographic findings of tensor fascia lata tendinopathy: another cause of anterior groin pain. Skeletal radiology. 2002;31(3):143-8.