Part of the BJSM’s #KnowledgeTranslation blog series

Two days ago, we published the first ‘big picture’ scientific overview detailing the relationships between rugby union, and health and wellbeing. Some of the main findings from the scoping review are summarised in the animation, and in the thread below. However, you might want some more detail around the findings, and you might want some context in which to apply these.

Halo! please find the unroll here: @SteffanGriffin: Out today in @BJSM_BMJ #HotOffThePress The relationships between rugby union, and health and… https://t.co/0F3vuBXuT1 See you soon. 🤖

— Thread Reader Unroll Helper (@UnrollHelper) October 29, 2020

To help you, we thought we’d start first of all, with what doesn’t this research show?

- That there are no ‘negatives’ to participating in rugby union

We should make it clear that this review doesn’t blindly advocate that there are only benefits to rugby participation, and that there are no potential adverse health outcomes. What this review does, is provide groups (such as players, parents, teachers, and policymakers) with an objective overview of the data so that they can make an informed choice about participating in rugby, where previously the only scientific information available was around the risks involved.

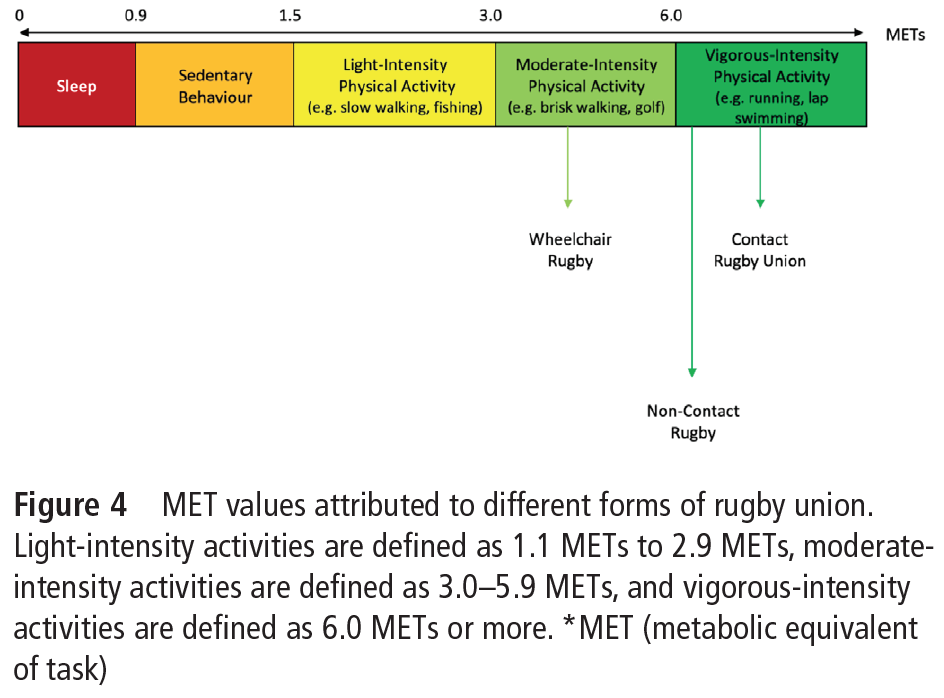

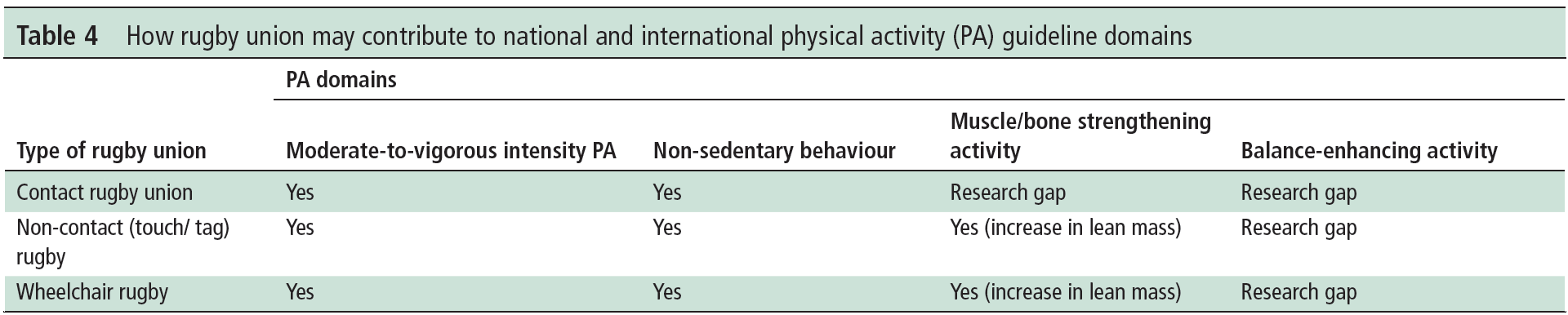

The scoping review has been able to show that rugby union (be that contact, non-contact, or wheelchair forms of the game) is able to provide health-enhancing moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity and counts as non-sedentary behaviour. We also know that many national population surveys (such as Health Survey England etc) ‘count’ rugby union as an activity that can provide muscle-strengthening/balance improvement when accrued for period of over 10-minutes.

There is also evidence that ‘ball sports’ can improve muscle function, bone health and balance, which this scoping review reinforces. Whilst this may sound intuitive to some, this is the first review of its kind to provide an evidence-informed ‘big picture’ overview of the literature, and is the first to show how rugby union ‘fits in’ to international guidelines around Physical Activity (such as those in the graphic below), which we know is a hugely important public health priority.

- That non-contact rugby is ‘better’ than contact forms of rugby

The scoping review separates the results by contact, non-contact and wheelchair forms of the game. By separating the results into not only different forms of rugby, but by different outcome measures (such as cardiovascular health, mental health etc), we hope readers can now clearly relate the scientific evidence to the form of rugby it relates to.

Although we have categorised the results by ‘forms’ of rugby however, we warn readers against using the study to purely compare contact to non-contact forms of the game for example, as the study was not designed to perform this task in a scientific manner. There are different types of study for each form of rugby, as well as a huge variety in the quality of studies (and in some sections there are no studies to even allow a comparison), so we would warn against a ‘like-for-like’ comparison . Whilst this review might stimulate a conversation around the type of rugby one might want to participate in, or what a school/club might want to offer children etc, it is outside the scope of this review to claim that there are ‘more benefits’ to participating in non-contact rugby union (such as touch/tag).

How we might suggest you use this scoping review? Using cycling as an example:

Steffan, the first author of the scoping review, works at an Accident & Emergency Department in London, and he usually cycles to work. During his shifts, he will sometimes see patients who have sustained (sometimes life-changing) injuries whilst cycling. Whilst each injury is a stark reminder of the potential dangers of cycling, Steffan values the fact that by cycling he can incorporate some physical activity into his working day, and he enjoys the fresh air. Whilst he is aware of the injury data concerning cycling in London, he is also aware of large population-based studies that have shown that cycling as a mode of transport is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all-cause mortality. Steffan is able to balance the benefits (both anecdotal and scientific) with the risks, and makes an informed decision that he will continue to cycle to work, but will continue to maximise the chances of keeping safe by wearing a helmet, high-visibility clothing, and adhering to the Highway Code.

Prior to this scoping review, the only scientific evidence available to make an informed decision was around the risks of rugby participation. This would be akin to Steffan basing his decision purely on the experiences of seeing cycling related injuries, and from papers describing the risks of cycling in London, and as a result deciding not to cycle, potentially missing out on the benefits. Whilst further research within rugby is needed in many domains (which the PhD will try to address), this is the first piece of work that allows people to make a more informed decision around participation.

We hope this blog has provided some clarity and some context, get in touch with us via social media if you have any questions or comments! For more content, please do visit our website

Authors and Affiliations:

Dr Steffan Arthur Griffin

Junior Doctor | PhD Student: Rugby Union, and Health & Wellbeing | RFU Sports Medicine Training Fellow

References: