Part of the BJSM’s #KnowledgeTranslation blog series

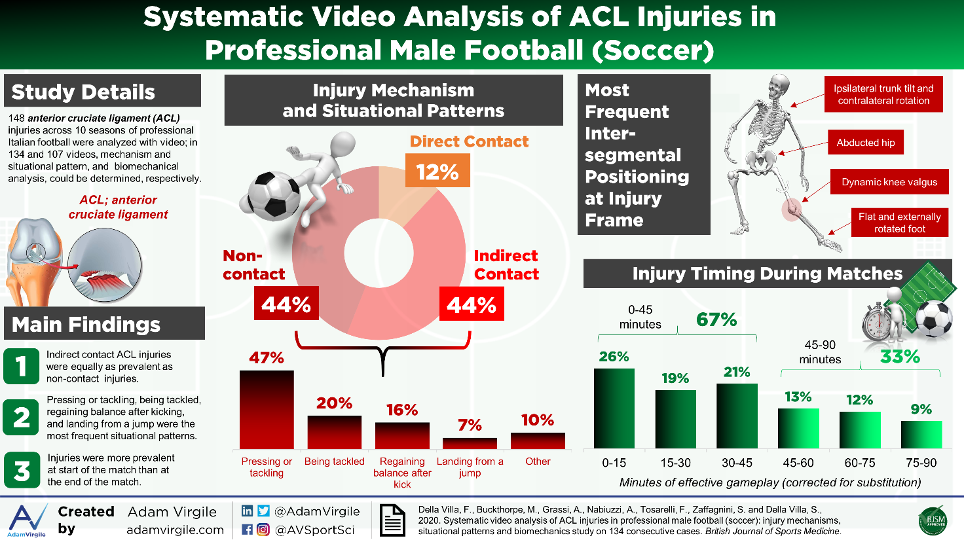

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries are a serious concern for the football player. While there is an increasing trend for these injuries [1], the media dimension of ACL injuries is continuing to grow. 50% of these concerning injuries can be prevented [2], but conclusive data are lacking for male athletes. The first step in injury prevention is understanding how a certain injury happens, therefore the aim of our study was to describe ACL injury mechanism across 10 seasons of Serie A and Serie B.

We studied over 134 ACL injuries, describing how, where and when they do happen [3]. Here are the full infographics of the paper for a quick look.

How ACL injuries happen

Describing ACL injury causation was the core of our study, splitting into three main levels, the first level was (1) injury mechanism, we found that:

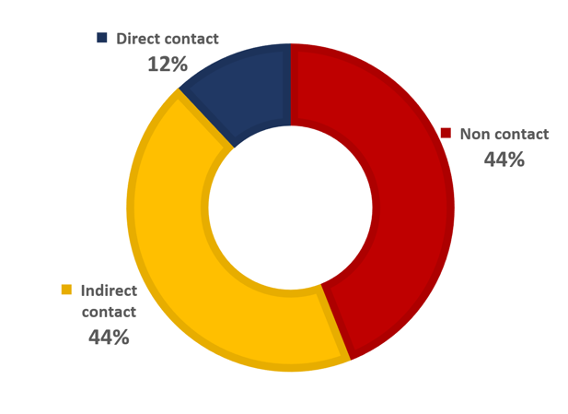

- 88% of injuries were indirect (IC) or non-contact (NC) (thus potentially preventable)

- IC injuries are as prevalent as NC injuries

- Only 12% of ACL injuries involved a direct contact to the knee

- In IC injuries (44%) we found a crucial role of mechanical perturbation (mostly, but not limited to the upper body) that triggered the ACL injury

- In NC injuries (44%) we found a crucial role of neurocognitive perturbation, a deceiving action from the opponent or a distraction (200-250 ms before the IC) that triggered high risk knee positioning.

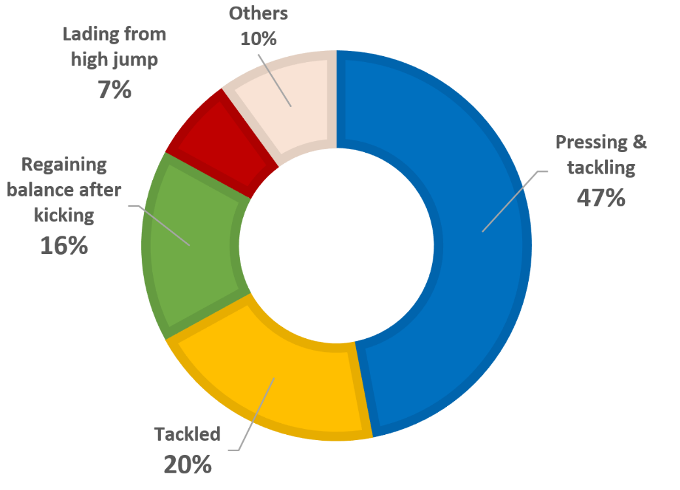

The second level of description entails the (2) situational patterns of NC and IC ACL injuries.

- 68% of ACL injuries were defensive;

- 4 main situational patterns were identified;

Examples of defensive “pressing/tackling” injuries:

Examples of offensive or duel “tackled” injuries:

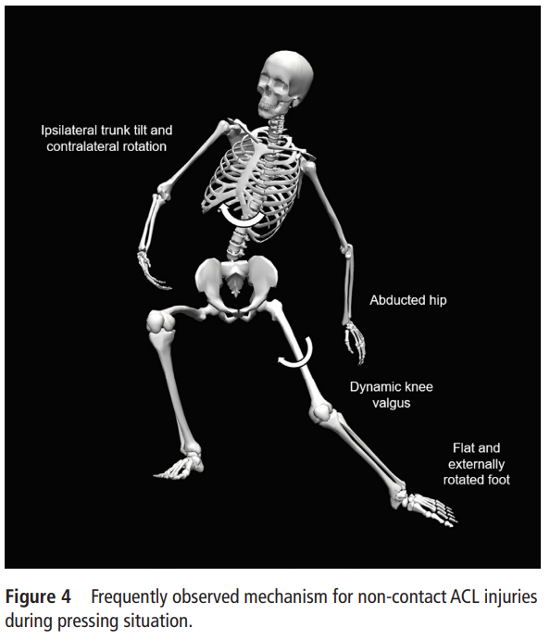

The third and last level of the how is (3) biomechanics, with the most frequent mechanism being a dynamic knee valgus (81%) on an early flexed knee and hip.

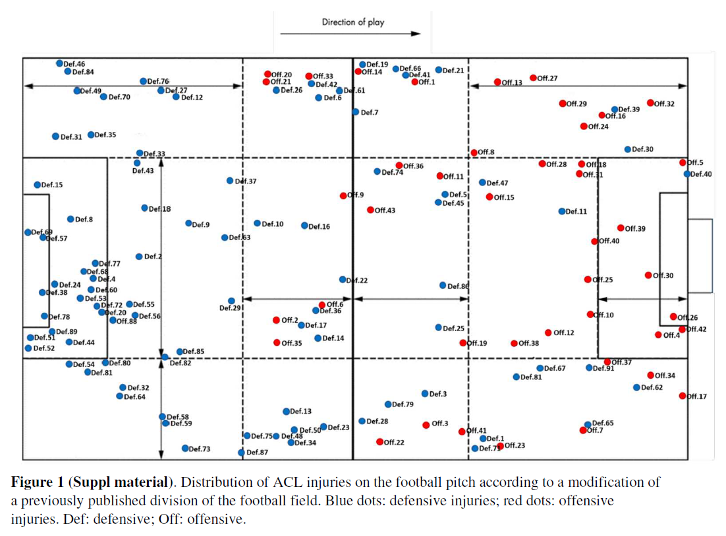

Where ACL injuries happen

- More injuries happen in the defensive third

- Defensive box and lateral corridors are the higher risk areas

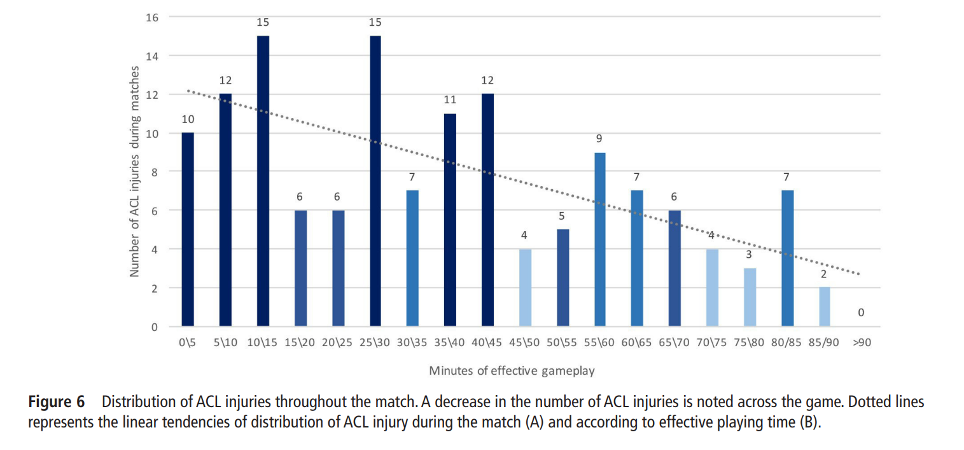

When ACL injuries happen

- Contrary to the general belief, ACL injuries are more frequent in the first half (62%) and particularly in the first 45 minutes of gameplay (68%)

- 25% of all ACL injuries happened in the first 15 minutes of the match.

- In term of seasonal distribution, the highest peak is at the beginning (September-October)

What are the take home points?

- Almost 9 out of 10 football ACL injuries happen with non-contact (44%) or indirect contact (44%) injury mechanism and thus a part of these injuries can be prevented.

- Four main situational patterns were identified with “pressing/tackling” (47%) and “tackled” (20%) injuries accounting for 67% of all NC or IC injuries.

- Regarding non-contact injuries, a key aspect we identified was a neurocognitive perturbation immediately before the initial contact to the ground, often seen in pressing situational patterns. It can be useful to train pressing technique also considering the neurocognitive aspect of the movement alongside biomechanics, including decision making. Very aggressive pressing style is a risky behavior for ACL injury.

- Regarding indirect contact injuries, the key point was a mechanical perturbation, generally involving the upper body, common in tackling and moreover tackled Advanced perturbation training, training for optimal stability at landing can be a useful addition to 1st and 2nd ACL injury reduction programs.

- Biomechanically dynamic knee valgus on a knee dominant movement pattern is the predominant mechanism of ACL injuries even in male footballers.

- Player to player engagements, especially in the defensive third and on the lateral corridors are the inciting events of many ACL injuries.

- A high proportion of ACL injuries happen in the first minutes of game play. This suggests a key role of inadequate neuromuscular readiness during intense engagements at the beginning of the match, rather than accumulated fatigue over the course of the match.

Authors and Affiliations:

Francesco Della Villa 1 MD, Matthew Buckthorpe 1 PhD, Alberto Grassi 2 MD, Alberto Nabiuzzi 1, Filippo Tosarelli 1, Stefano Zaffagnini MD, Stefano Della Villa 1 MD

1 Education and Research Department, Isokinetic Medical Group, FIFA Medical Centre of Excellence, Bologna, Italy

2 IIa Clinica Ortopedica e Traumatologica, Istituto Ortopedico Rizzoli, Bologna, Italy

References:

- Waldén M, Hägglund M, Magnusson H. ACL injuries in men’s professional football: a 15-year prospective study on time trends and return-to-play rates reveals only 65% of players still play at the top level 3 years after ACL rupture. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:744-50.

- Webster KE, Hewett TE. Meta-analysis of meta-analyses of anterior cruciate ligament injury reduction training programs. J Orthop Res 2018;36:2696-2708.

- Della Villa F, Buckthorpe M, Grassi A, et al. Systematic video analysis of ACL injuries in professional male football (soccer): injury mechanisms, situational patterns and biomechanics study on 134 consecutive cases. Published 2020 Jun 19. Br J Sports Med. 2020. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101247.

The authors declare no competing interests in this field