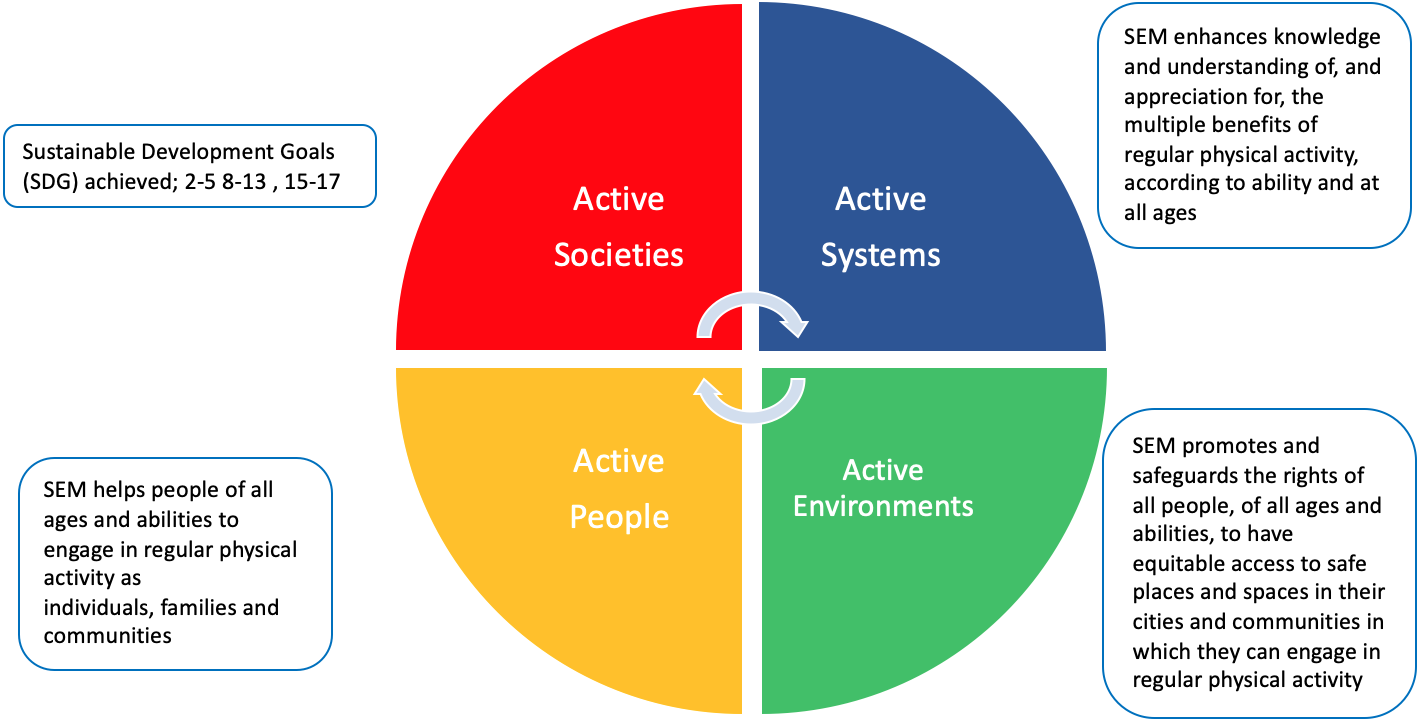

The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged and changed global society with profound health implications. The lockdown and travel restrictions have provided an unique opportunity for populations and individuals to engage in physical activity. Some nations, such as the UK, have embedded exercise as an essential exception to leave the home in the strictest phase of the lockdown guidance. During the crisis, sports and exercise medicine (SEM) clinicians have been redeployed to clinical roles on the frontlines and working in unfamiliar roles. The lockdown has provided space to reimagine the role of SEM as a speciality in a post COVID-19 world. In the immediate term, SEM is uniquely placed to assist in many areas to “build back better” (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Highlights the strategic links to the WHO #GAPPA guidance, 13 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals and the opportunities for the global SEM community and individuals to reimagine their contributions to health systems post Covid-19

Physical inactivity is one of the leading causes of non-communicable disease (NCDs) related premature death worldwide. Forces that include rapid unplanned urbanization, globalization of unhealthy lifestyles and population ageing add to this complex nature of NCDs and ill health. Many of these issues can be addressed through the Sustainable Development Goals and it is timely to explore how SEM can contribute to these wide ranging ambitions for #HealthForAll.1 Now more than ever, we have the opportunity to reimagine models of care in our communities, to reinvestigate our evidence base, to fine tune our change agency and to reflect on resource allocations.

Time for a whole system change?

The growth of SEM in the UK was born out of the Olympic legacy. These current MDT based- systems highlight the growth of sports medicine practice and provide a framework to reimagine and manage the complexities of post COVID care and global priorities. Now the time is to look at the gaps and strengths with a broader, international strategic review of the profession and it’s systems giving priorities to improving equity and multi-skilled working.

We need future SEM professionals to –

- Reduce the risk of deconditioning in both Covid-19 patients with post viral fatigue and also in people who are somehow isolated like those in care homes and care at home services

- Work collaboratively with other healthcare professionals (HCPs) to provide holistic care and manage the complex disease burden of NCDs, inequities and influence the social determinants of health such as poverty

- Work with undergraduate healthcare students to tackle the burden of an inactive society. One example would be to build awareness around campaigns such as “End PJ Paralysis” (a global multi-disciplinary approach to reducing inactivity, frailty and deconditioning in health and social care systems)2

- Inform policy on the interrelatedness of physical activity and health, active transport, urban design, climate change and outdoor activity, and model more home-based activities

The unique value of SEM clinicians is their skillset within the multidisciplinary team to diagnose, treat and manage delivery of care for active and inactive individuals at all levels of society. A key capacity is the use of exercise for rehabilitation and indeed for health promotion. Healthcare systems globally have reacted responsively to the pandemic, transforming care provision. This impetus should be focussed to transform the way we deliver SEM care to patients with comorbidities within societal challenges. Integration of these services, where patients receive skilled support from a range of healthcare professionals are in use by various organisations and are highly valued by patients and the communities they serve.

Refocusing our implementation model

Whilst the exercise medicine and physical activity evidence base has grown significantly over past decades; a focus should prioritise implementing best practice. There is strong, unequivocal data on the importance of physical activity in the primary and secondary prevention of chronic disease.3 We do not have the same level of evidence on which interventions are the most effective and we must source translational studies on multifaceted physical activity interventions.4 More emphasis needs to be driven towards implementing international policies such as the World Health Organisations’ Global Action Plan of Physical Activity (GAPPA).1 SEM can also play a key part in supporting the achievement of many of the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations.1 This opportunity was highlighted recently through the ‘Healthy Together” campaign, an International Olympic Committee (IOC) & World Health Organisation (WHO) partnership designed to spotlight the collective effort and global collaboration needed to promote health and reduce the negative impact of COVID-19.2

Strengthening the frontlines; supporting practitioners

A key component of future proofing the SEM strategy is to support incoming trainees and junior clinicians to provide care to a society with increased risks of inactivity and comorbidities.5 Key policies for example which guide action in the UK such as Health Education England Future Doctors document and the General Medical Council’s ‘Outcomes for Graduates’ framework highlight the need for graduates and future clinicians to be skilled in leadership, and drive forward complexity within multi-professional teams.6 These will be used to inform national and international professional bodies, as well as medical and health schools themselves, of the necessary change agency needed to ensure that the future health practitioner has the skills, competencies and adaptive mindset needed to deliver the very best care to patients and improve health and social care systems. As a specialty, SEM should reform the way we develop interest in the speciality at an early stage amongst undergraduates. This can be done via established schemes such as the NHS Leadership Academy School for Change Agents approach and harnessing successful leadership models such as the UK Council of Deans of Health student leadership programme (150 Leaders) and Universitas 21 initiatives. Is it time we had a well-supported global SEM leadership program?

The Post COVID-19 world and implications for SEM action

Now is the opportunity to reimagine the level of impact and influence SEM as a speciality can deliver. To realise these ambitions, as nations seek to rebuild health systems fit for future system challenges, requires strategic SEM action now!

SEM must initiate collaborative influence on how society invests, transitions and places itself moving into a different new normal where sustainability, active travel and healthier systems are embedded. As we act and foster multidisciplinary networks within SEM for a post-Covid future, ask yourself this- what actions can you take, who will you create opportunities for, where will SEM fit in the build back better, and what will success for SEM’s contribution look and feel like?

Authors and Affiliations

Pandya Ta*, Elliott Jb*, Arora A c,d, Thornton J e,f, Gates AB g

*- denotes joint first authorship

a- Royal Preston Hospital, Sharoe Green Lane, Preston, PR2 9HT

b- Ulster Hospital, Upper Newtownards Road, Dundonald, Belfast, BT16 1RH

c- University Hospital of North Midlands, Newcastle Road, Stoke on Trent, ST4 6QG

d- Keele University, Keele, Newcastle, ST5 5BG

e- Department of Family Medicine, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada

f-Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada

g – Division of Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Nottingham, Clinical Sciences Building, Hucknall Road, Nottingham, NG5 1PB

References

- UNOSDP, 2018. Sport And The Sustainable Development Goals. [online] Available at: <https://www.un.org/sport/sites/www.un.org.sport/files/ckfiles/files/Sport_for_SDGs_finalversion9.pdf> [Accessed 30 May 2020].

- International Olympic Committee. (2020). Sport and physical activity should be part of post-COVID-19 recovery plans, say governments – Olympic News. [online] Available at: https://www.olympic.org/news/sport-and-physical-activity-should-be-part-of-post-covid-19-recovery-plans-say-governments [Accessed 31 Jul. 2020].

- End PJ Paralysis. 2020. End PJ Paralysis. [online] Available at: <https://endpjparalysis.org> [Accessed 30 May 2020].

- Thornton, J.S., Frémont, P., Khan, K., Poirier, P., Fowles, J., Wells, G.D. and Frankovich, R.J., 2016. Physical activity prescription: a critical opportunity to address a modifiable risk factor for the prevention and management of chronic disease: a position statement by the Canadian Academy of Sport and Exercise Medicine. Br J Sports Med, 50(18), pp.1109-1114.

- American College of Cardiology, 2016. Exercise Prescription: The Devil Is In The Details. [online]Available at:<https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2016/02/11/08/15/exercise-prescription> [Accessed 30 May 2020].

- International Federation of Medical Student Associations, 2018. Global Priorities Of Medical Education. [online] Available at: <https://issuu.com/ifmsa/docs/global_priorities_in_medical_educat> [Accessed 30 May 2020].

- GMC, 2018. Outcomes For Graduates. [online] Available at: <https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/dc11326-outcomes-for-graduates-2018_pdf-75040796.pdf> [Accessed 29 May 2020].

- Health Education England. 2020. Future Doctor. [online] Available at: <https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/future-doctor> [Accessed 31 May 2020].

Contributorship Statement: TP and JE conceived the idea. ABG, JT, AA substantially edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript

Funding: None

Competing Interests: There are no competing interests for any author

Acknowledgements : None