COVID-19 public health restrictions continue to ease and sport is back. Resumption of sporting activity may not be linear and there is no room for complacency as small numbers of cases can quickly become big clusters. Many sporting bodies are grappling with the best way to protecting players, staff, officials and fans from COVID-19. The AIS Framework provides a safe and considered roadmap out of the COVID-19 restrictions that recognise the unique concerns and context associated with professional and high performance sport.(1) In this blog we discuss the complex and logistically challenging process of rebooting professional and high performance sport from an Australian perspective. The principles discussed below are applicable to other settings.

The first step of preparation for sport resumption include includes education of the athletes and other personnel, to promote and set expectations for the required behaviours prior to recommencing activities. It should not be presumed that athletes and other personnel have an accurate appreciation of the health risks. Therefore, a structured process to improve health literacy around COVID-19 is imperative. We recommend mandatory completion of Australian Government COVID-19 infection control training module for all medical and allied health staff.

Assessment of the sport environment and agreement on training scheduling to accommodate social distancing, protocols in place for illness management. The approach to training should focus on ‘get in, train, get out’, minimising unnecessary contact in change rooms, bathrooms and communal areas. Special consideration should be made for para-athletes and others with medical conditions as they may be more vulnerable to COVID-19 infection.

The second step of proposed criteria for resumption of sporting activity include three levels (Levels A, B, C) of sporting activities. Click here for detailed descriptions of recommended sport specific activities. A graded return to sport is recommended to mitigate injury risk from sudden increase in training loads. It should be noted that, evidence of transmission issues within the sporting cohort or local community may influence the timing of progression between levels. It is important to reiterate that all sport resumption decisions must be based on State and Territory COVID-19 public health advice.

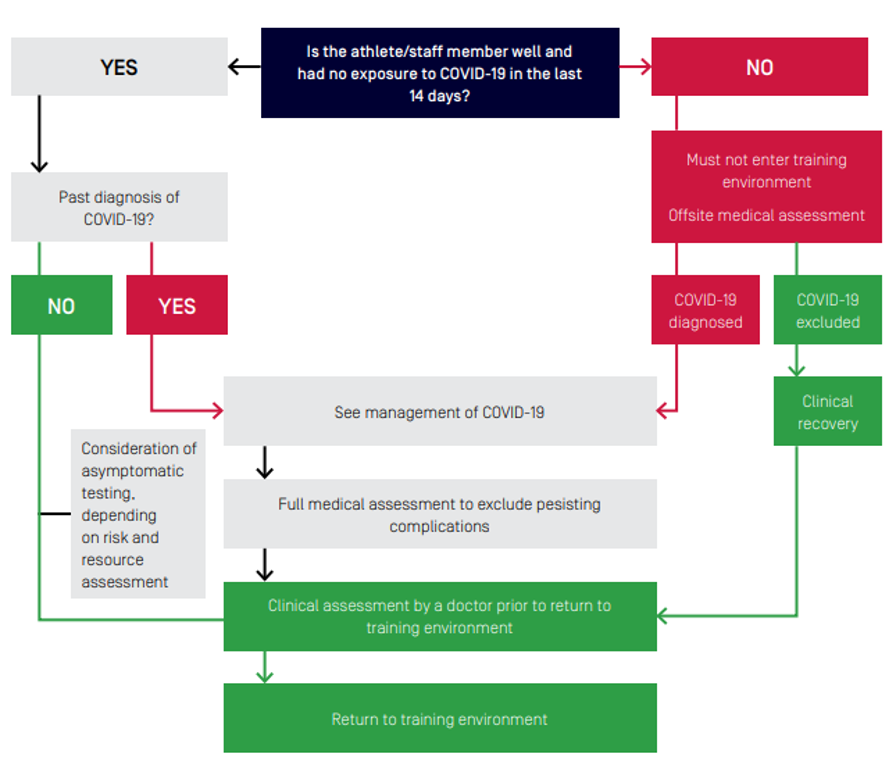

The below figure illustrates the recommended assessment of athletes/staff prior to resumption of formal training activities.

If an athlete or staff have been unwell or had contact with a known or suspected case of COVID-19 in the past 14 days, they must not join the training environment until cleared to do so by a medical doctor. Athletes returning to sport after COVID-19 infection require full medical assessment to resumption of high intensity physical activity to minimise risk of complications. Organ systems affected by COVID-19 in the acute phase and recommended assessment considerations for athlete and other personnel returning to sport environment are summarised in the table below.

| Organ system | Acute complications associated with COVID-19 | Potential implications for returning athletes/other personnel | Assessment and investigation considerations |

| Respiratory | Pneumonia- Lung abnormalities have been seen on CT chest of symptomatic and asymptomatic cases(2-4)

ARDS(5) |

Reduced aerobic capacity and increased respiratory distress.

Potential persisting restrictive lung patterns and reduced diffusion capacity. These long-term respiratory complications been reported follow previous coronavirus epidemics (SARS, MERS) in non-athlete populations.(6) |

Clinical assessment

Graded exercise testing, VO2 max testing FBE, CRP, spirometry, lung ultrasound, chest x-ray, CT chest Respiratory review |

| Cardiovascular | Cardiomyopathy(7)

Myocarditis(8) Pericardial effusion(9) Arrythmias(8, 10) Autoimmune mimicry of vasculitis and thrombosis(11, 12) |

A return to exercise with underlying cardiac complications could be contraindicated for some.(13)

Return to contact sports / trauma could be contraindicated for some. Persisting inflammatory states. |

Clinical assessment

12-lead ECG, troponins, coagulation profile, CRP, echocardiogram, cardiac MRI D-dimer, ferritin, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentary rate Cardiology review |

| Neurological | Multiple symptoms and signs have been described.(14)

Guillain–Barré syndrome(15) Elevated D-dimer (16, 17) Stroke(18) Encephalopathy(19) |

Currently unclear as the neurological sequalae from mild to moderate cases is yet to be elucidated.

Post intensive care syndrome |

Clinical assessment

FBE, D-dimer, MRI brain Neurology review |

| Gastrointestinal / hepatic | Deranged liver function tests (LFTs)(20)

Some acute COVID-19 cases present with gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms. |

Consider COVID-19 in patients presenting with combined respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms.(20)

Increased risk from hepatically excreted medications. |

Clinical assessment

LFTs Gastroenterology review |

| Renal | Acute renal impairment(21) | Persistent subclinical renal impairment could be a risk on returning to high intensity training. | Clinical assessment.

UECs, urine dipstick/specific gravity Renal review |

| Fatigue | Commonly associated with viremia | Post-viral fatigue is known to occur following other viral infections(22) and may occur with COVID-19. | Monitoring of self-report measures, fatigue symptoms and training loads. |

| Mental health | Symptoms of depression and anxiety(23)

Both were more common in patients with less social support(24) |

Potential increased risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety.(13)

Persistent depression and anxiety have been reported following previous coronavirus epidemics in non-athletic populations. |

Clinical assessment

Screening questionnaires Psychology review and psychiatrist review

|

While there is increasing research on the multi-organ nature of COVID-19 in the acute phase, there is currently limited evidence on medium to long-term complications. Long-term decreased exercise capacity has been noted following previous related coronavirus infections (SARS and MERS).

A structured ongoing management process is in place to ensure early detection of illness within the training group is imperative. Monitoring of athletes and staff could include adding a respiratory symptoms checklist to daily wellness monitoring, with automated follow up of reported symptoms, regular screening (brief symptom check, resting heart rate and temperature) of athletes (if medical resources are available). Any individual with respiratory symptoms (even if mild) should be considered a potential case and must immediately self-isolate, have COVID-19 excluded and be medically cleared by a doctor to return to the training environment. Isolation of close contacts will be a decision for medical staff, based on case specific details

In the event of a positive COVID-19 case, staff should work closely with the Local Public Health Authorities who will direct further action that needs to be taken. Training facilities may be closed on the instruction of the Local Public Health Authority or the CMO. Re-opening of the training facility should only occur after close consultation with the Local Public Health Authority.

Medical servicing (physiotherapy and manual therapy) specific to Level A, B, C sporting activities can be found here.

The AIS Framework is a timely tool for ‘how’ reintroduction of sport activity occurs based on the best available evidence to optimise athlete and community safety. The overriding priority for sport is to ensure that any return to sport activity does not endanger public health.

For more details listen to the Sport rebooting in the #COVID-19 environment podcast

Authors and Affiliations:

Nirmala Perera1, Richard Saw1, David Hughes1 – Australian Institute of Sport

@Nim_Perera @_RichardSaw @DrDavid_Hughes @theAIS

References

- Hughes D, Saw R, Perera N, et al. The Australian Institute of Sport framework for rebooting sport in a COVID-19 environment. J Sci Med Sport. 2020;23(7):639-63.

- Hu Z, Song C, Xu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 24 asymptomatic infections with COVID-19 screened among close contacts in Nanjing, China. Sci China Life Sci. 2020.

- Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Resp Med. 2020.

- Buonsenso D, Pata D, Chiaretti A. COVID-19 outbreak: less stethoscope, more ultrasound. Lancet Respir Med. 2020.

- Peng Q-Y, Wang X-T, Zhang L-N, et al. Findings of lung ultrasonography of novel corona virus pneumonia during the 2019–2020 epidemic. Intensive Care Medicine. 2020.

- Ahmed H, Patel K, Greenwood D, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes in survivors of coronavirus outbreaks after hospitalisation or icu admission: A systematic review and meta-analysis of follow-up studies. medRxiv. 2020:2020.04.16.20067975.

- Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020.

- Driggin E, Madhavan MV, Bikdeli B, et al. Cardiovascular considerations for patients, health care workers, and health systems during the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020.

- Bao C, Liu X, Zhang H, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) CT findings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020.

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061-9.

- Zhang Y, Xiao M, Zhang S, et al. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020.

- Zhang W, Zhao Y, Zhang F, et al. The use of anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of people with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): the perspectives of clinical immunologists from China. Clin Immunol. 2020;214:108393-.

- Hull J, Loosemore M, Schwellnus M. Respiratory health in athletes: facing the COVID-19 challenge. Lancet Respir Med. 2020.

- Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, et al. Neurologic Features in Severe SARS-CoV-2 Infection. N Engl J Med. 2020.

- Toscano G, Palmerini F, Ravaglia S, et al. Guillain–Barré Syndrome Associated with SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020.

- Wang Y, Wang Y, Chen Y, et al. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures. J Med Virol. 2020.

- Wu Y, Xu X, Chen Z, et al. Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav Immun. 2020.

- Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, et al. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of Covid-19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020:e60.

- Poyiadji N, Shahin G, Noujaim D, et al. COVID-19–associated Acute Hemorrhagic Necrotizing Encephalopathy: CT and MRI Features. Radiology. 2020;0(0):201187.

- Tay S, Teh KKJ, Wang L, et al. Impact of COVID 19: perspectives from gastroenterology. Singapore Med J. 2020.

- Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, et al. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97(5):829-38.

- Wessley S, David A, Butler S, et al. Management of chronic (post-viral) fatigue syndrome. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1989;39(321):171-3.

- Kong X, Zheng K, Tang M, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with depression and anxiety of hospitalized patients with COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020:2020.03.24.20043075.

- Zhang J, Lu H, Zeng H, et al. The differential psychological distress of populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Brain Behav Immun. 2020.