The drive for distance

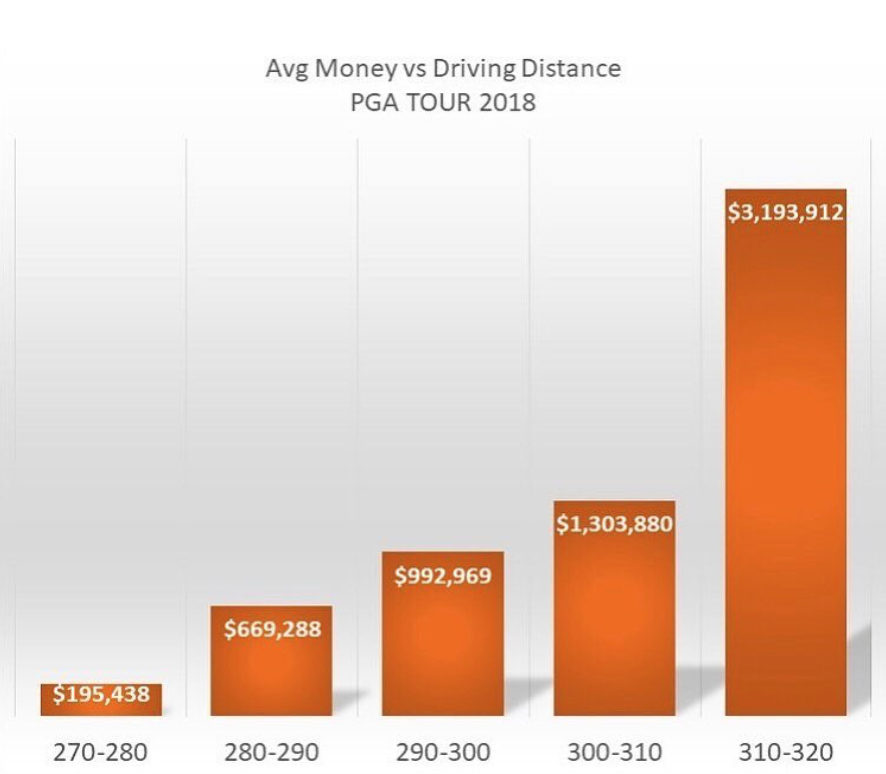

The recent body transformation of Bryson DeChambeau has taken a large amount of media focus in recent months. Is there a benefit to increasing your size and muscle mass? Will it help my golf game? Will I hit it further? Will it lead to injury? Will it prevent injury? These are some of the common questions often asked when people talk about Bryson or other strong proponents of Strength & Conditioning (S&C) such as Tiger Woods, Rory Mcllroy, Brooks Koepka and Lexi Thompson. However, it is the rapid change in body shape and associated increase in driving distance that has propelled Bryson to the forefront of the discussion, bringing the topic back into the media limelight once again. Clubhead speed (CHS) has become a key determinant of performance in the modern game. The current top 50 of the world rankings is dominated by those that simply hit the ball the furthest. Indeed, the figure below highlights the huge jump in prize money associated with consistently exceeding a 310 yard drive in men’s game. A variety of factors enable the world’s best to hit the ball as far as they do. These are both technical and physical in nature and are therefore both coachable (skills) and trainable (physicality/athleticism). This article will focus on the trainable factors underpinning CHS and in particular those commonly pursued in the gym i.e. strength and power qualities. These can be (somewhat crudely) further sub-divided into qualities which aid the generation of propulsive force (angular momentum) and those which enable the player to dissipate and control those forces. At the European Tour Performance institute (ETPI) we use the analogy of upgrading the engine size (propulsive force) and ensuring a robust chassis (dissipative force).

Figure 1. Average money vs Driving Distance: PGA Tour 2018 Statistics

Upgrading the Engine Size: Propulsive Force Generation

Research has shown that low-handicap golfers regulate ground reaction forces to control shot distance,1 and that the downswing is initiated from the ground up, transferring energy upstream through the kinetic chain to the club head.2 Not only is there substantial evidence showing positive relationships between various strength and power measures and clubhead speed3,4,5, but significant clubhead speed gains have been observed (in elite players) in parallel with improvements in such measures.6 Importantly, on occasion these increases in CHS have been attributed to increases in body mass, since both strength and power levels and technique have remained relatively unchanged.7 This provides insights into the mechanisms by which increased body mass facilitates longer drives, which clearly go beyond the notion that a larger muscle can produce more force. Indeed, being heavier has the added benefit of creating a greater anchoring effect, allowing the player to retain more stability at higher swing speeds. Many golfers are concerned with their relative strength and power; often tracking progress with measures such as vertical jump height but their sport doesn’t require them to project their body like a sprinter or a basketballer, it is their absolute strength and power that matters. By way of example, due to his increases in body mass, Bryson DeChambeau’s vertical jump height may well be lower (or similar) than when he first began his training programme, but his momentum at take-off will almost certainly be higher (he is more powerful, but not relative to body mass) and it is this which relates more strongly to CHS.3 It is therefore the concomitant increase in force generation capacity and body mass that has likely led to the impressive driving statistics we are witnessing from him this year. An increased ability to generate angular momentum from the ground up, together with an ability to resist the centrifugal force he has generated, (partly) secondary to his increased body mass. Both isometric and eccentric strength through the hip and trunk will also facilitate the latter which leads us onto a discussion around the importance of creating a robust chassis.

Creating a Robust Chassis: Force Dissipation

All other factors equal, whenever we increase CHS we will inherently increase injury risk – swinging the club faster is associated with higher torques and more stress on the body. It is therefore essential that whenever we upgrade the ‘engine size’ we also ensure we develop a ‘robust chassis’ and effective brakes. “You can’t speed up what you can’t slow down” and “you can’t shoot a cannon from a canoe” are two common sayings to describe this concept. Regardless of how much Bryson raised his ability to express propulsive ground reaction force, this couldn’t be realised in his swing without an ability to control and decelerate effectively. As discussed, an increased body mass will reduce the burden on the chassis (by making it easier to reduce the centrifugal force), but inter-segmental strength is vital to control torques and prevent stress from concentrating on certain anatomical structures – commonly the lower back, neck and wrist.9 Indeed, the injuries we see on tour are overwhelmingly overuse presentations9 associated with issues like spikes in volume of balls being hit, or at times of swing/club changes (which often are linked to hitting more balls/volume than the bodies tissues are used too). In addition to appropriate education around load management to help avoid these spikes, there are essentially two approaches we can take to reduce the chances of a structure becoming overloaded: 1) reduce the stress going through the structure and 2) increase the load the structure can tolerate. Together with input from the golf coach (changes in technique) increasing inter-segmental strength and control can help address the former but a degree of stress/strain is inevitable. Therefore, it is also advisable to raise the work capacity of the relevant musculature (& body tissues) to enable the player to control and dissipate torques repeatedly at a lower maximum voluntary contraction – essentially creating a ‘force buffer’; helping the body withstand load and resist fatigue.

All other factors equal, whenever we increase CHS we will inherently increase injury risk – swinging the club faster is associated with higher torques and more stress on the body. It is therefore essential that whenever we upgrade the ‘engine size’ we also ensure we develop a ‘robust chassis’ and effective brakes. “You can’t speed up what you can’t slow down” and “you can’t shoot a cannon from a canoe” are two common sayings to describe this concept. Regardless of how much Bryson raised his ability to express propulsive ground reaction force, this couldn’t be realised in his swing without an ability to control and decelerate effectively. As discussed, an increased body mass will reduce the burden on the chassis (by making it easier to reduce the centrifugal force), but inter-segmental strength is vital to control torques and prevent stress from concentrating on certain anatomical structures – commonly the lower back, neck and wrist.9 Indeed, the injuries we see on tour are overwhelmingly overuse presentations9 associated with issues like spikes in volume of balls being hit, or at times of swing/club changes (which often are linked to hitting more balls/volume than the bodies tissues are used too). In addition to appropriate education around load management to help avoid these spikes, there are essentially two approaches we can take to reduce the chances of a structure becoming overloaded: 1) reduce the stress going through the structure and 2) increase the load the structure can tolerate. Together with input from the golf coach (changes in technique) increasing inter-segmental strength and control can help address the former but a degree of stress/strain is inevitable. Therefore, it is also advisable to raise the work capacity of the relevant musculature (& body tissues) to enable the player to control and dissipate torques repeatedly at a lower maximum voluntary contraction – essentially creating a ‘force buffer’; helping the body withstand load and resist fatigue.

Conclusion

When carried out under the guidance of suitably qualified professionals (who ensure good technique and a graduated increase in activity) there are very few injuries caused by Strength & Conditioning training itself. With growing evidence to suggest that strength training reduces both acute and overuse sports injuries,9 together with the specific benefits of strength training on golf performance described herein, and general health and wellbeing benefits widely documented, the benefits greatly outweigh the risks and S&C will continue to be a hugely important area for players across all levels of the game.

Authors & Affiliations:

Nigel Tilley – Physiotherapist (ETPI – European Tour)

Simon Brearley – S&C Coach (ETPI – European Tour)

References

- McNitt-Gray, J.L., Munaretto, J., Zaferiou, A., Requejo, P.S. and Flashner, H. (2013) ‘Regulation of reaction forces during the golf swing’, Sports Biomechanics, 12(2), pp. 121–131.

- Nesbit, S.M. and Serrano, M. (2005) ‘Work and power analysis of the golf swing’, Journal of Sports Science and Medicine, 4(4), pp. 520–533.

- Wells JE, Charalambous LH, Mitchell AC, Coughlan D, Brearley SL, Hawkes RA, Murray AD, Hillman RG & Fletcher IM. (2019). Relationships between Challenge Tour golfers’ clubhead velocity and force producing capabilities during a countermovement jump and isometric mid-thigh pull. Journal of Sports Sciences. 37(12):1381-6

- Coughlan D, Taylor M.J, Jackson J, Ward N & Beardsley C. (2020). Physical characteristics of youth elite golfers and their relationship with driver clubhead speed. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 34(1), 212-217

- Read PJ, Lloyd R, De Ste Croix M, Oliver J. Relationships between field-based measures of strength and power and golf club head speed. J Strength Cond Res. 27: 2708–2713, 2013.

- Coughlan, D., Tilley, N. & Brearley, SL. (2019) Training Champions – Andrea Pavan. ETPI Blog.

- Brearley, SL, Coughlan, D. & Tilley, N. (2019) Training the Modern Golfer: Jazz Janewattananond. ETPI Blog.

- Smith, MF and Hillman R. (2012) A retrospective service audit of a mobile physiotherapy unit on the PGA European Golf Tour. Phys Ther Sport; 13:41–4.

- Laurensen, JP, Andersen, TL. & Anderson LB. (2018) Strength training as superior, does-dependent and safe prevention of acute and overuse sports injuries: a systematic review, qualitative analysis and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine; 52:24.