A proposal to guide in “terra incognita”

How can elite athletes and para-athletes (hereafter referred as “athletes”) manage the return to performance by minimizing injury risk after this lockdown period due to Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic? We assume that, beyond the health-related clinical consequences of COVID-19 and/or lockdown – including COVID-19-related risk of cardiopulmonary decompensation – and despite efforts to maintain overall fitness (e.g., training initiatives, nutritional and sleep) without compromising their immune system and mental health,1 athletes may be at higher risk of injury when they will return to normal training and sport performance. We therefore aim to propose practical tips to help athletes in this challenging come back.

Athletes constitute a unique cohort of individuals facing this specific challenge such as potential infection susceptibility due to training, difficulty to execute highly-skilled movements, reduced interactions with coaches and access to training facilities, or competition rescheduling, in addition to adherence to universal guidelines for social distancing and personal hygiene.1 Given the absence of historical and scientific references to guide athletes’ return to performance following COVID-19 lockdown, stakeholders should rely on “indirect” detraining,2 space/bedrest-3 and injury-related knowledge,4 by taking into account each athlete’s status and lockdown situation.

A window of opportunity?

While the first 3-4 weeks of the lockdown elicit detraining (e.g., muscle mass and power loss, decline in sprint- and endurance-related physiological and performance outcomes), it provides a “window of opportunity”.5 While likely resembling an inter-season transition period,5 it adds a stress due to uncertainty (e.g., COVID-19 and season reprogramming). But how much down time is too long? With lockdown extended up to a minimum of 8 weeks in many countries, the “minimum effective dose” to maintain/attenuate the decay of endurance- and neuromuscular-related performance factors is unlikely to meet the specific exercise recommendations aiming to decrease respiratory tract infection risk (i.e., 30-60 min at 60-80% of maximum capacity, 3-5 days per week).1 More importantly, the “home-work” fitness regimes are probably poorly effective for athletes, in particular if they did not reach their sport-specific requirements (e.g., maximal musculoskeletal tension during specific movement such as sprinting or throwing). Such condition will place athletes at higher injury risk when restarting “real-world” sport. Interestingly, some medical recommendations in elite soccer only focused on strength and endurance maintenance (with submaximal stimulus level) and ignore speed-related explosive movements.6 Due to the different time course of both muscle and tendon adaptations during detraining and that 8 weeks of sub-maximal resistance training are not sufficient to increase tendon stiffness,7 adding maximal mechanical loading appears paramount during the lockdown in order to reduce the injury risk when returning to sport and performance. In addition to the decrease in relative training time, possible lower mechanical loading during lockdown-induced daily life could not be excluded, likely altering postural muscles and joint dynamic stability. As such, ensuring that muscle-tendon units spend a sufficient time under tension (e.g., daily displacements, walking, low-to-moderate velocity running) is also a preventive prerequisite, in addition to the required sport-specific maximal mechanical loading.

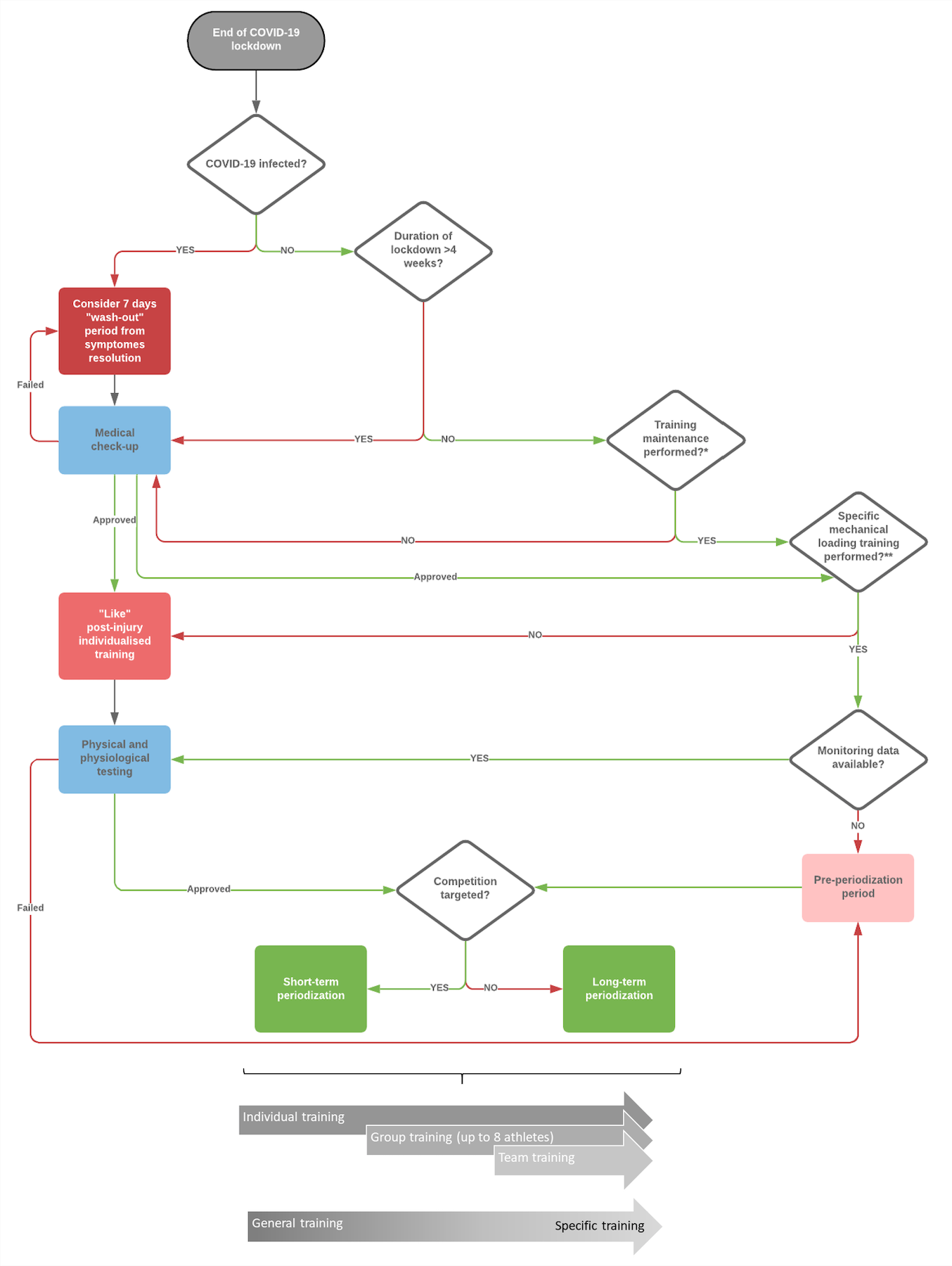

Depending on lockdown conditions (e.g., material availability, training monitoring, staffs’ follow-up), athletes will resume to training with different fitness level in reference to their sports-specific requirements. To date, only Godfrey et al.8 reported the effect of an 8-week detraining period in an elite rower: rapid fitness improvements were observed after 8 weeks of retraining but 20 weeks of training were necessary to return to the athlete’s previous fitness level. If training maintenance helps reducing the detraining effect in “normal” situation, the magnitude of detraining during the present COVID-19 lockdown remains unknown. Caution is thus warranted during the retraining period, bearing in mind the need for a personalised approach based on the athletes’ individual status on the various physical and psychophysiological determinants of performance within their specific sport. Furthermore, any COVID-19 infection and/or related clinical sequelae, as well as lockdown duration must be carefully considered.6 Therefore, post-COVID-19 retraining must be tailored according to various steps and individual considerations (Figure 1) and taking into account COVID-19-prevention measures (e.g., social distancing, regular hand washing). The first stage must include a medical check-up (including COVID-19 testing) before initiating the screening of lockdown and training maintenance condition that will serve to build an appropriate periodization. If inadequate training is detected, intermediate stages must be implemented with a personalised progression including sport-specific movements reintroduction. Once entering return to performance stage (last step), training must respect an evolution from general-to-specific training, and from individual-to-group or team training. In all steps, rigorous COVID-19-related safety practices remain of primary importance to avoid any COVID-19 transmission.

Figure 1. A proposal to guide in “terra incognita”: Flow chart of key steps and consideration to tailor a personalised sport-specific post COVID-19 healthy return to performance in elite athletes and para-athletes.

* All training type (i.e., endurance, strength, power, agility, sprint and flexibility) must be considered; ** Including sufficient daily mechanical loading.

To conclude, within the public health general COVID-19 recommendations, a healthy athletes’ return to performance process should follow key steps related to each individual’s status, and follow a progressive and appropriate retraining periodization while minimising (de)training musculoskeletal and COVID-19-related cardiorespiratory risks. Accordingly, sport governing stakeholders should allow appropriate time to the athletes before resuming to competition.

Authors & Affiliations

Franck Brocherie1*, Gaël Guilhem1, Pascal Edouard2,3, Sébastien Le Garrec4, Grégoire Millet5, Jean-Benoit Morin6

1 Laboratory Sport, Expertise and Performance (EA 7370), French Institute of Sport (INSEP), Paris, France.

2 Inter‐university Laboratory of Human Movement Science (LIBM EA 7424), University of Lyon, University Jean Monnet, F-42023, Saint Etienne, France.

3Department of Clinical and Exercise Physiology, Sports Medicine Unit, University Hospital of Saint-Etienne, Faculty of Medicine, Saint-Etienne, France.

4 Medical Department, French Institute of Sport, Paris, France.

5 Institute of Sport Sciences, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland.

6 Université Côte d’Azur, LAMHESS, Nice, France.

The authors declare no competing interests

References

- Hull JH, Loosemore M, Schwellnus M. Respiratory health in athletes: facing the COVID-19 challenge. Lancet Respir Med 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30175-2 [published Online First: 2020/04/12]

- Mujika I, Padilla S. Detraining: loss of training-induced physiological and performance adaptations. Part II: Long term insufficient training stimulus. Sports Med 2000;30(3):145-54. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200030030-00001 [published Online First: 2000/09/22]

- Steele J, Androulakis-Korakakis P, Perrin C, et al. Comparisons of Resistance Training and “Cardio” Exercise Modalities as Countermeasures to Microgravity-Induced Physical Deconditioning: New Perspectives and Lessons Learned From Terrestrial Studies. Front Physiol 2019;10:1150. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01150 [published Online First: 2019/09/26]

- Soligard T, Schwellnus M, Alonso JM, et al. How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury. Br J Sports Med 2016;50(17):1030-41. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096581 [published Online First: 2016/08/19]

- Silva JR, Brito J, Akenhead R, et al. The Transition Period in Soccer: A Window of Opportunity. Sports Med 2016;46(3):305-13. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0419-3 [published Online First: 2015/11/05]

- Eirale C, Bisciotti G, Corsini A, et al. Medical recommendations for home-confined footballers’ training during the COVID-19 pandemic: from evidence to practical application. Biol Sport 2020;37(2):203-07. doi: 10.5114/biolsport.2020.94348

- Kubo K, Ikebukuro T, Yata H, et al. Time course of changes in muscle and tendon properties during strength training and detraining. J Strength Cond Res 2010;24(2):322-31. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181c865e2 [published Online First: 2009/12/10]

- Godfrey RJ, Ingham SA, Pedlar CR, et al. The detraining and retraining of an elite rower: a case study. J Sci Med Sport 2005;8(3):314-20. doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(05)80042-8 [published Online First: 2005/10/27]