By Sean Carmody1,2, Andrew Murray1,3,4, Mariya Borodina5, Vincent Gouttebarge6,7, Andrew Massey8

The COVID-19 pandemic has had, and will have, profound effects on every person on earth. Measures advocated by the World Health Organisation (WHO), and put in place by National Governments, businesses and individuals will save millions of lives, but current movement restrictions (i.e., various degrees of lockdown) cannot continue indefinitely. The activity restrictions imposed by governments are designed to reduce human-to-human transmission—they buy time and allow international collaboration between governments and internally to build and allocate the resources and systems to:

- TEST – every suspected case where testing is merited and available, while having effective prevention strategies in place

- TRACE – follow-up all confirmed cases of COVID-19 and contact trace every relevant contact to identify and cut off transmission

- TREAT – manage all cases effectively, with adequate Intensive Care Unit (ICU) capacity, ventilators and staff

Rightly, professional sport has been placed on hold during the COVID-19 pandemic. The WHO (#BeActive) and many governments continue to promote certain types of moderate physical activity for the benefits it confers on the immune system, physical and mental health1-4. Sport has health, social and economic benefits for individuals and society, and when the COVID-19 pandemic is better ‘controlled’, it may be appropriate to reintroduce community sport, and professional sport. In this editorial, we opine on what needs to be in place for professional sport to recommence.

Emerging from Lockdown—Public Health

The restrictions placed on activities and businesses are likely to ease up over a gradual period and time-frames will differ across nations and even within nations. The following is expected5:

- Lockdowns will be lifted strategically, and in a stepwise fashion—the effects of easing will be carefully monitored given the two-week latency between actions (e.g., allowing more social engagement) and outcomes (no change in infection rates or an increase in cases)

- Countries and/or regions with lower community transmission of cases will begin easing restrictions before those with higher community transmission

- Physical distancing and enhanced standards of personal hygiene will continue longer term. Some, like regular handwashing, should be part of routine behaviour forever.

- Risk assessment (systematically looking at risk and potential consequence of COVID-19) and control measures designed to eliminate, reduce or minimize the risks will be in place.6,8,9

Risk Assessment of Sporting Events

Mass gatherings such as a large number of participants and particularly crowds attending sporting events likely increase risk of transmission of COVID-19,7. Additionally, there are some sports (for example golf, time trial cycling) where social distancing is possible, and others (e.g., football, rugby) where it is not practical. Travel (use of airports, hotels) can also increase risk, although this may be no different to travel on other business. If professional sport is to return in the near future, event organisers must accept that assessment of risk must be undertaken, and measures put in place to ensure any risks from the event are less than the benefits.

The WHO highlights 5 key factors in determining risk:

- Will the event be held in a country that has documented active local transmission of COVID-19 (community spread)?

- Will the event be held in a single venue or multiple venues/cities/countries?

- Will the event include international participants (athletes and spectators) from countries that have documented active local transmission of COVID-19 (community spread)?

- Will the event include a significant number of participants (athletes or spectators) at higher risk of severe COVID-19 disease (e.g., people over 65 years of age or people with underlying health conditions)?

- Will the event include sports that are considered at higher risk of spread for COVID-19 (eg, contact sports)?

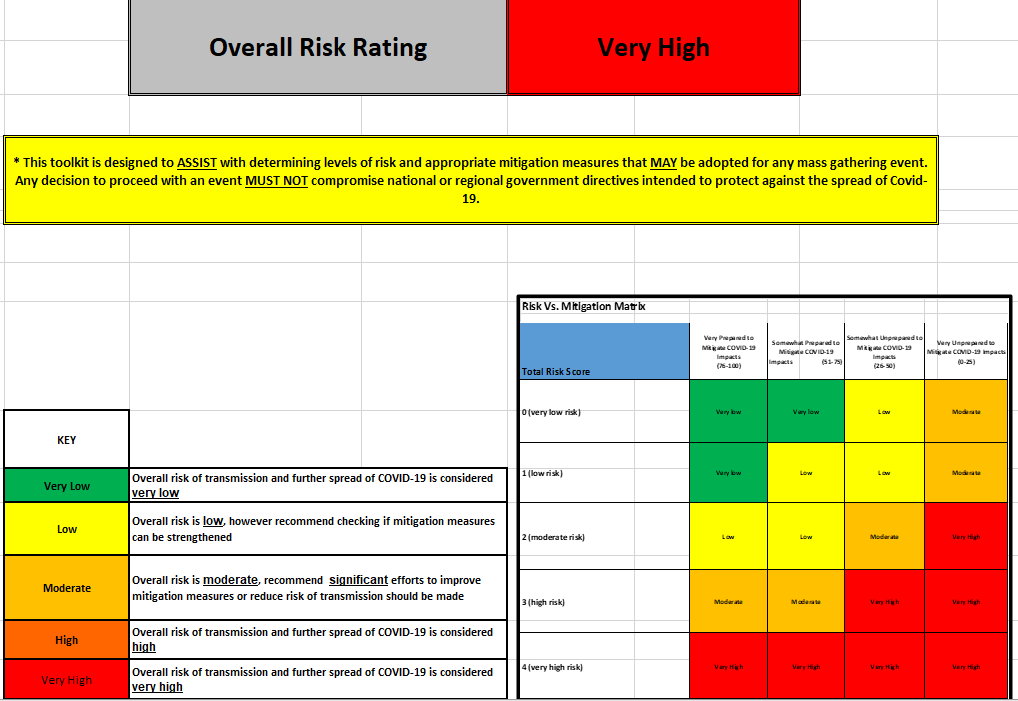

We illustrate below in Figure 1, that for a non-closed doors, English Premier League football match, played in April, the risk is very high, and the match should not proceed regardless of government policies, which at present would also preclude it going ahead.

Figure 1. Risk Analysis for English Premier League football hosted in April.

Once the risk assessment is conducted, event organizers should refer to mitigation measures to see where to incorporate these considerations in the planning of the events, to further decrease the risk of spread of COVID-19.

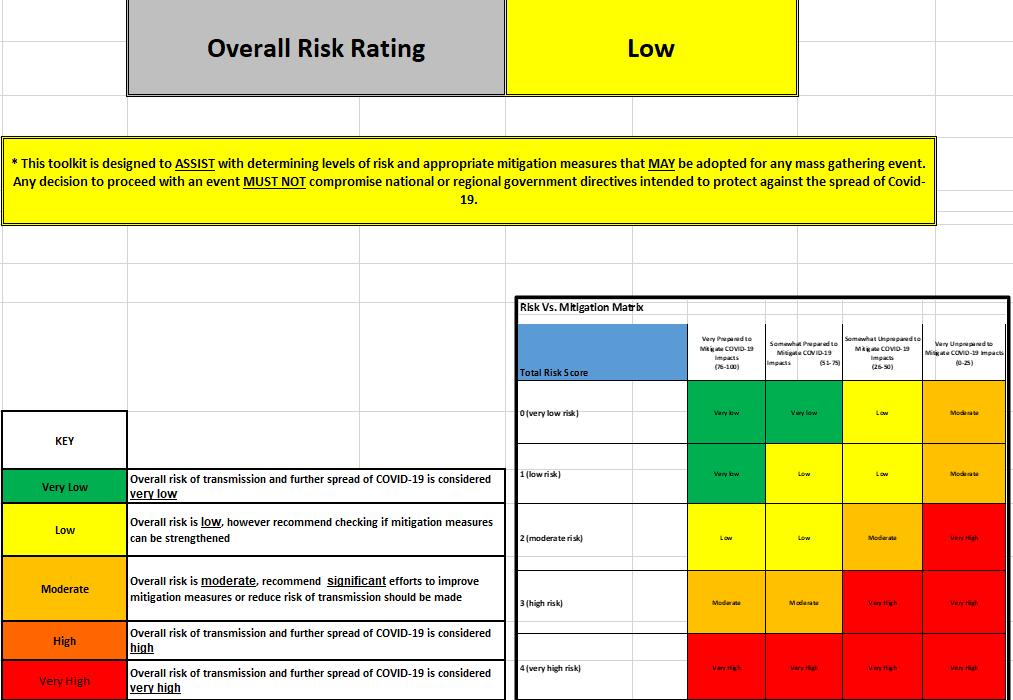

If for example a match was postponed to August and played behind closed doors, with organisers enforcing hygiene measures, social distancing where practical, and also planned for TEST and TRACE measures, and transmission was (for illustration) present, but significantly less in the host country, then the risk can be reduced to low.

Figure 2. Risk assessment for a closed doors English Premier League football match, where local transmission is reduced, and risk mitigation procedures put in place.

Players would need to have time to gain fitness prior to matches resuming. Discussion with government, local health authorities, event organisers and the participants could take place, regarding suitability to proceed and what other controls can further decrease risk.

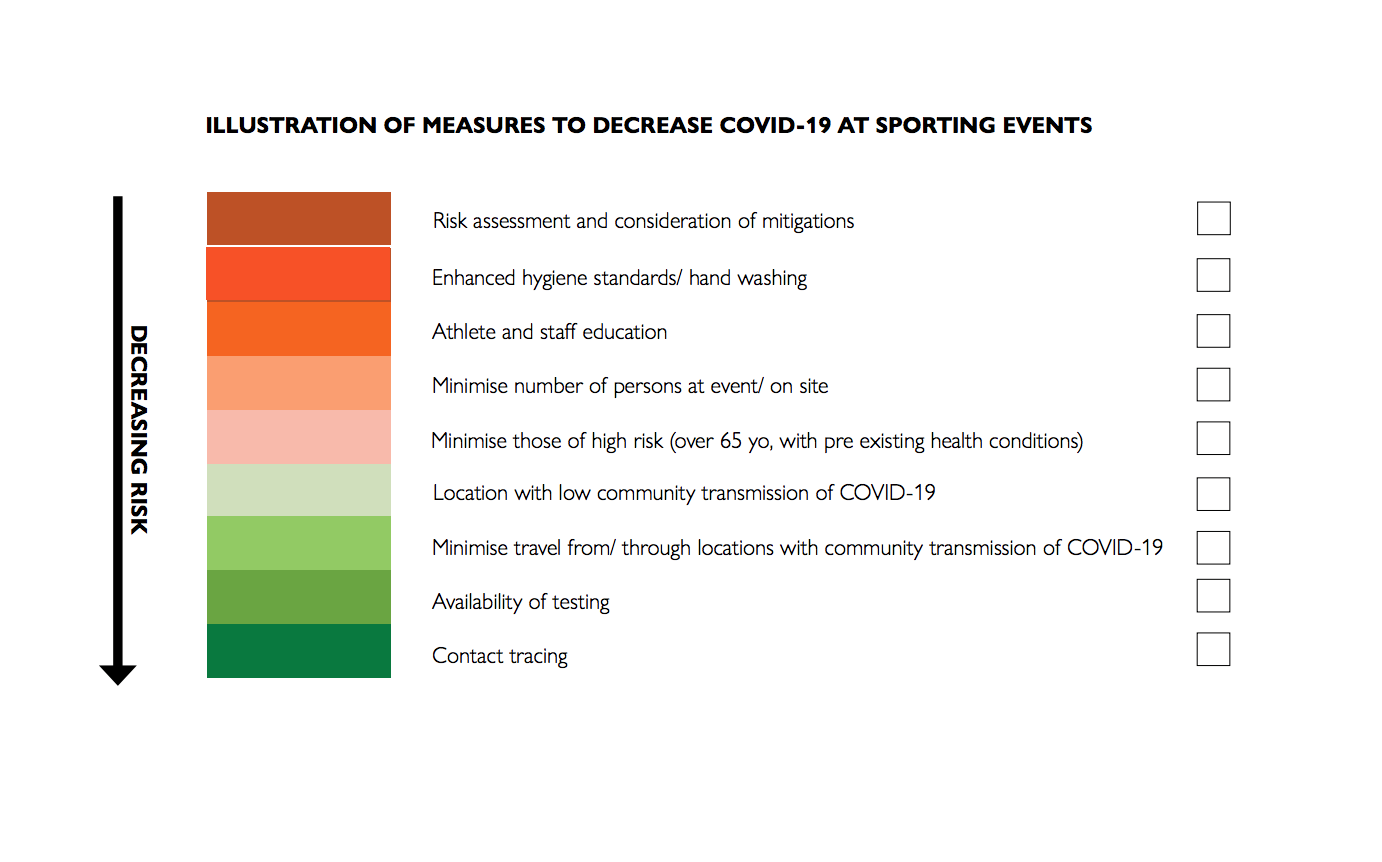

If community transmission is low, and adequate risk mitigation procedures are in place, the overall risk can be very low. This could apply to a local golf competition, where the sport is outdoors, social distancing is possible, participants are <65 years old, fit and well. Key measures to decrease risk of COVID-19 at sporting events are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Illustration of options to decrease risk of sporting events during the COVID-19 pandemic

We suggest the following documents serve as guidance to those undertaking risk assessments for events within their sports:

- WHO Key Planning Recommendations for Mass Gatherings6

- WHO Considerations for sports federations/sports event organizers when planning mass gatherings in the context of COVID-198

- WHO Mass Gathering Sporting Risk Assessment9

If sporting events return, close liaison with the participants, local / national government and public health authorities is necessary. Event organisers must:

- Minimise risk of transmission for all groups of sporting event participants

- Work to ensure readily available accurate testing, while not taking these from health systems that need them most

- Be able to accurately contact trace

Further important steps include individual sporting bodies producing guidance regarding return to training post restrictions, policies and procedures for testing, and management of players diagnosed with COVID-19, recognising that the science is fast evolving.

Conclusion

Professional sport, and its resumption, is a secondary concern in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic globally. However, international collaboration has enabled major sporting events to proceed during WHO declared Public Health Emergencies, including Vancouver 2010 Olympic Games during H1N1 pandemic, and Rio 2016 Olympic Games during Zika outbreak. We should start planning to resume sporting events, given the health, social and economic benefits of professional sport and the substantial planning and work required prior to any resumptions. In this editorial, we build on WHO guidance and tools and discuss the factors and risk assessments which should be in place prior to sport returning.

***

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge input received from Amaia Artazcoz Glaria, Maurizio Barbeschi, Fiona Bull and Albis Francesco Gabrielli – World Health Organisation; Andy Sinclair-Scottish Government and Anna Deignan, UK Government.

Authors

Sean Carmody1,2, Andrew Murray1,3,4, Mariya Borodina5, Vincent Gouttebarge6,7, Andrew Massey8

- Medical and Science Department. PGA European Tour Golf. Various.

- Medical Department, Queens Park Rangers Football and Athletic Club, London, UK

- Sport and Exercise, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

- Medical Department. Scottish Rugby Union. Scotland, UK

- Academy of Postgraduate Education under FSBU FSCC of Federal Medical-Biological Agency of Russia. Russia.

- Football Players Worldwide (FIFPro), Hoofddorp, The Netherlands

- Amsterdam UMC, Univ of Amsterdam, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Amsterdam Movement Sciences, Meibergdreef 9, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

- Medical Department. Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), Zurich, Switzerland

Corresponding author:

Dr Sean Carmody: seanocearmaide@gmail.com

Competing Interests

SC, AMu, VG, AMa, receive remuneration from sporting organisations as per author affiliations.

References

- Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT et al., Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. The Lancet. 2012 Jul 21;380(9838):219-29.

- Brolinson PG, Elliott D. Exercise and the immune system. Clinics in sports medicine. 2007 Jul 1;26(3):311-9.

- World Health Organisation. Be Active During COVID-19- Press Briefing. World Health Organisation, 2020. Accessed 16/4/2020 https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/be-active-during-covid-19

- UK Government, Coronavirus (COVID-19): what you need to do. https://www.gov.uk/coronavirus [Accessed 14th April 2020]

- World Economic Forum. Prepare for a ‘new normal’ as lockdown restrictions ease. Monday’s WHO Covid-19 Briefing. World Economic Forum, 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/13-april-who-briefing-coronavirus-covid19-lockdown-restrictions-guidance/

- Key planning recommendations for Mass Gatherings in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance. Mar 19, 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/key-planning-recommendations-for-mass-gatherings-in-the-context-of-the-current-covid-19-outbreak

- Rashid H, Haworth E, Shafi S, Memish ZA, Booy R. Pandemic influenza: mass gatherings and mass infection. The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 2008 Sep;8(9):526.

- Considerations for sports federations/sports eventorganizers when planning mass gatherings in the context of COVID-19. April 14, 2020 https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331764/WHO-2019-nCoV-Mass_Gatherings_Sports-2020.1-eng.pdf

- Mass Gathering Sporting Risk Assessment. April 14, 2020 https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/points-of-entry-and-mass-gatherings

- McCloskey B, Zumla A, Ippolito G, Blumberg L, Arbon P, Cicero A, Endericks T, Lim PL, Borodina M, Group MG. Mass gathering events and reducing further global spread of COVID-19: a political and public health dilemma. Lancet (London, England). 2020 Apr 4;395(10230):1096.