By Coral L Hanson @HansonCoral, Paul Kelly @narrowboat_paul, Alice Pearsons @AlicePearsons, Chloe Williamson @Chlobobs_, Sheona McHale @SheonaMchale, Steven Hanson @SteveFloatBoat and Lis Neubeck @lisneubeck

The COVID-19 global pandemic is rapidly changing the way that we live. Suddenly, large numbers of people are working from home, leisure facilities are closed, and we’re social distancing from our family and friends. The benefits of physical activity for health are well known and emphasised in the 2019 UK physical activity guidelines.[1] Understanding how to build some physical activity into your new stay-at-home reality can help keep you healthy, calm, and connected.

Every time you are active, your mental health improves

We gain short-term mental health benefits from each bout of activity, so doing even small amounts is worthwhile. Physical activity of any intensity is good for your mood.[2,3] It does not matter what type of activity you choose. Different forms of exercise; walking,[4] cycling,[5] yoga,[6] dance aerobics,[3] tai chi[7] and running[8] all trigger similar positive mental health benefits. If you are unable to go out, changing your normal activities to something that you can do indoors will help your mental health. For example, replacing your normal cycling activity with an online dance aerobics class will also help maintain your aerobic fitness, while replacing it with yoga will help with strength, balance and mental health. Anything is good, but more is better. This means that whatever your starting point, doing a bit more activity will help to combat social isolation and anxiety.[9]

Breaking up sitting time

A major change to physical activity levels for those now working at home is the loss of active commuting to work or other journeys, and the incidental activity of moving around the office. In normal times, office workers spend approximately 70% of an eight-hour workday sitting.[10] The move to home working could potentially increase this. Workplace studies have examined how to increase incidental physical activity while at work- and these same principles apply to working at home. Evidence indicates that using three different strategies can help; standing up (if you are able) at least every 30 minutes; sitting less by aiming for approximately equal amounts of sitting and standing time, and moving more by increasing the type of physical activity you do just from one activity to another.[11] Some practical tips are that you can set reminders (use your online diary or phone) to stand up every 30 minutes, walk to get water regularly, or stand when you feel uncomfortable and need to change position. If you have an adjustable desk at home, try to spend equal amounts of time standing and sitting. If not, you can sit less by standing during online meetings and telephone calls. Be creative and use other things in your home to make a standing desk. We found that cardboard boxes on top of our desks work well. If you are chairing an online meeting, initiate a standing culture at the beginning. Move more by combining every other 30-minute stand up with walking laps around your house. If you have stairs, make sure that you include them in your lap. If you have more than one toilet in your house, use the one furthest from where you are working.

Moving for 1-2 minutes every half an hour is enough to break up your sitting.[12] You can perform body weight exercises in small spaces and with little equipment. For example, calf-raises, knee to elbow and standing wall press-ups target strength, flexibility, coordination and balance. More advanced exercise such as lunges, squats and sit-ups are alternatives for those who are already active. If you do not have any fitness equipment, look around your home and see what you can use instead. For example, you can use tins of food as hand weights for upper body strength exercises.

Physical distancing, social connectedness and the use of technology

The new guidelines about social distancing mean that it may be impossible to be active with friends. Technology offers those who are self-isolating a way to connect with friends, family and colleagues. Studies using mobile apps have shown that texting has a positive effect on increasing physical activity.[13] You can encourage your friends and family to be more active via telephone, text or social media. If you want to know how much activity you are doing, mobile apps that count steps and press-ups are almost limitlessly available. Regardless of starting levels, there are a range of beginner to advanced online resources such as yoga workouts or entertainment dance apps that you can use at home. If you normally use a leisure facility, check whether they are offering online classes or look for established commercial virtual classes. Creating a definite schedule for activity by signing up to join a timetabled session will help to establish a routine.

Take the opportunity to engage with those self-isolating with you (your family and pets). Play fetch with the dog in the garden if you have one, have a quick game of hide and seek with your children or grab a paintbrush with your partner to repaint that bathroom ceiling. It does not matter what you do, how much you do or how you do it, any increase in physical activity accompanied by increased connection to those around you will benefit your physical and mental health. Keep up to date with government guidelines about being active outside. If regulations allow, walk solo/with those you live with responsibly. Remember to keep a distance of two metres from anyone that you do not live with.

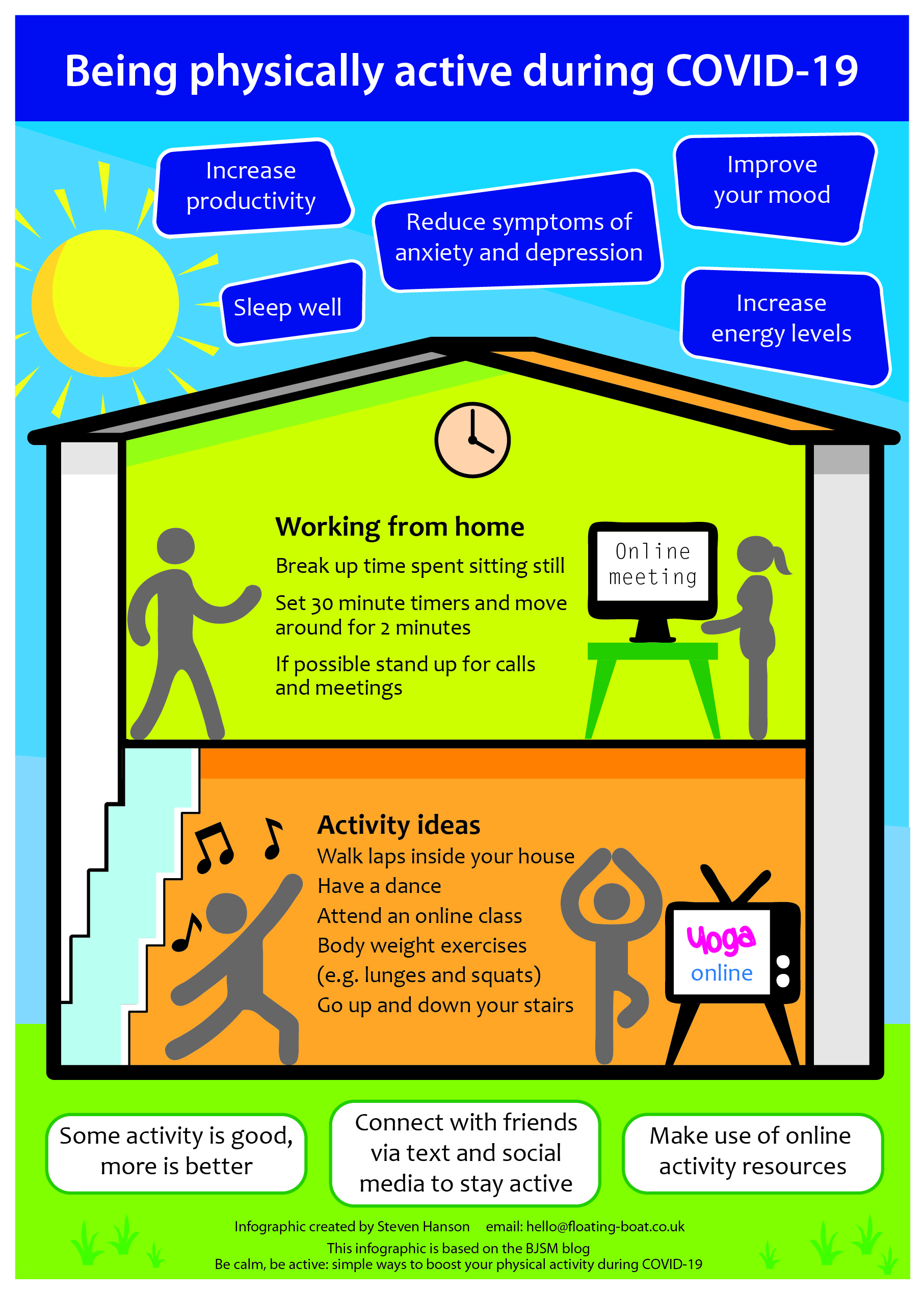

Being physically active during COVID-19: an infographic for the public

To make sure that the general public becomes or remains active during this global pandemic, we created this infographic using evidence-based principles on how to construct and deliver messages to promote physical activity.[14] We encourage you to share it with your channels.

Who is this infographic for? The infographic is for all adults aged 18-69 years who are working from, or staying at home. This population may have recently lost access to active travel, gyms etc. Some of these individuals may also be facing being at home with their children, and have the added challenge of keeping their children active.

What is the aim of the infographic? The aim of the infographic is to give people some ideas about how to remain active safely during the COVID-19 outbreak and to motivate them to do so. We hope this can encourage and improve one’s confidence to be active during this pandemic.

What is the content of the infographic? Evidence supports the use of gain-framed messages (information on the benefits of physical activity) with particular focus on the short-term social and mental health benefits. We have positively framed messages on links between physical activity and productivity, mood, stress, energy levels/fatigue, depressive symptoms, and anxiety. We have given practical examples or “how to” remain active during COVID19.

Our call to action! We encourage you to share this infographic with your friends and family using your social channels (Twitter, Facebook, WhatsApp etc.). You could also print it out and stick it on a wall at home to remind you to remain active!

***

Coral L Hanson 1, Paul Kelly 2, Alice Pearsons 1, Chloe Williamson 2 ,Sheona McHale 1, Steven Hanson 4, Lis Neubeck 1,3

1 School of Health and Social Care, Edinburgh Napier University, Sighthill Campus, Edinburgh, EH11 4DN, UK. Email: c.hanson@napier.ac.uk Tel: +44 7908861666

2 Physical Activity for Health Research Centre, Institute for Sport, Physical Education and Health Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

3 Sydney Nursing School, Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney, Australia

4 Floating Boat Design Solutions, Stocksfield, UK

Corresponding author:

Coral L Hanson: C.Hanson@napier.ac.uk

Other helpful links:

- Home-based strength and cardio workouts for adults: https://www.nhs.uk/oneyou/for-your-body/move-more/home-workout-videos/

- Seated strength and flexibility exercises for adults with mobility issues: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/sitting-exercises/

- Five-week strength and flex programme: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise/strength-and-flex-exercise-plan/

- Sport England have also produced a useful page: https://www.sportengland.org/news/how-stay-active-while-youre-home

References:

- UK chief medical officers, UK Chief Medical Officers’ Physical Activity Guidelines. [Date accessed 25/03/2020] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832868/uk-chief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf. 2019

- Woo M, Kim S, Kim J, Petruzzello SJ, Hatfield BD. The Influence of Exercise Intensity on Frontal Electroencephalographic Asymmetry and Self-Reported Affect. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2010;81(3):349-59. dio:10.1080/02701367.2010.10599683

- Rokka S, Mavridis G, Kouli O. The impact of exercise intensity on mood state of participants in dance aerobics programs. Studies in Physical Culture & Tourism. 2010;17(3):241-5.

- Kelly P, Williamson C, Niven AG, Hunter R, Mutrie N, Richards J. Walking on sunshine: scoping review of the evidence for walking and mental health. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(12):800. dio:10.1136/bjsports-2017-098827

- Petruzzello SJ, Snook EM, Gliottoni RC, Motl RW. Anxiety and mood changes associated with acute cycling in persons with multiple sclerosis. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2009;22(3):297-307. doi:10.1080/10615800802441245

- Vancampfort D, De Hert M, Knapen J, Wampers M, Demunter H, Deckx S, et al. State anxiety, psychological stress and positive well-being responses to yoga and aerobic exercise in people with schizophrenia: a pilot study. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33(8):684-9. doi:10.3109/09638288.2010.509458

- Wang C, Bannuru R, Ramel J, Kupelnick B, Scott T, Schmid C. Tai Chi on psychological well-being: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2010;10(1). doi:10.1186/1472-6882-10-23

- Nabetani T, Tokunaga M. The effect of short-term (10-and 15-min) running at self-selected intensity on mood alteration. J Physiol Anthropol Appl Human Sci. 2001;20(4):233-9. doi:10.2114/jpa.20.233

- Department of Health and Social Care. UKChief Medical Officers’ Physical Activity Guidelines [date accessed March 2020] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832868/uk-chief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf; 2019.

- Thorp AA, Healy GN, Winkler E, Clark BK, Gardiner PA, Owen N, et al. Prolonged sedentary time and physical activity in workplace and non-work contexts: a cross-sectional study of office, customer service and call centre employees. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:128-. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-9-128

- Healy G, Eakin E, Lamontagne AD, Owen N, Winkler E, Wiesner G, et al. Reducing sitting time in office workers: Short-term efficacy of a multicomponent intervention. Prev Med. 2013;57(1):43-8. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.04.004

- Carter SE, Jones M, Gladwell VF. Energy expenditure and heart rate response to breaking up sedentary time with three different physical activity interventions. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25(5):503-9. doi:10.1016/j.numecd.2015.02.00

- Mollee JS, Middelweerd A, Kurvers RL, Klein MCA. What technological features are used in smartphone apps that promote physical activity? A review and content analysis. Pers Ubiquitous Comput. 2017;21(4):633-43. doi:10.1007/s00779-017-1023-3

- Williamson C, Baker G, Mutrie N, Niven N, Kelly P. Get the message? A scoping review of physical activity messaging. 2020 Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. (2020;in press).