By Drs David Wyndham Lawrence, MD, MPH (@davidwlawrence1) and Robin Carhart-Harris, PhD (@RCarhartHarris)

Sports medicine as a discipline is uniquely situated to safely explore, research, adopt, and implement novel and innovative strategies to meet the mental and physical demands of athletes and physically active populations. Significant advances have been made in sports science; including nutrition, training, injury management and prevention, sleep optimization, and health technologies. However, the stigma surrounding mental health and wellbeing in athletes remains pervasive.1

Athletes encounter hundreds of distinct stressors2 making this population vulnerable to a spectrum of mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, substance misuse, burnout, and interpersonal-relationship issues.2,3 The stressors encountered by athletic populations include: (1) performance and personal issues (i.e. injuries, finances, career transitions, etc.); (2) leadership and personnel issues (i.e. spectators, media, governing bodies, coaches, support staff, etc.); (3) logistic and environmental issues (i.e. travel, selection, accommodation, physical safety, etc.); and (4) cultural and team issues (i.e. teammates behaviour, goals, cultural norms, team support, etc.).2 A recent meta-analysis and systematic review identified that mental health symptoms and disorders are widely prevalent in athletes and maybe be higher in elite athletes compared to the general population.3

The juxtaposition of sports medicine as a discipline, being uniquely innovative and committed to servicing the comprehensive needs of a vulnerable population with high demands, optimally situates it to critically explore and understand potential novel therapeutic interventions, particularly in regards to mental health and well-being. Moreover, sports medicine practitioners should be aware of advances and early research as it pertains to mental health, in order to conduct informed evidence-based discussions and recommendations with an increasingly knowledgeable patient population.

Psychoactive agents, defined as a ‘chemical substances that alter brain function resulting in alterations in mood, cognition, perception, behaviour, or consciousness’,4 are ubiquitous in the field of sports medicine. Stimulants, anxiolytic agents, and depressants are commonly used by athletes and prescribers to manage a multitude of conditions. A resurgence of attention is being placed on ‘psychedelics’ or ‘hallucinogens’, with early research suggesting a protective effect for the role of psychedelics in the management of a broad range of mental health disorders.4-9 Psychedelic agents are defined as substances that induce perceptual alterations, in addition to changes in mood, cognition, sense of self, and consciousness.4-8 Psychedelics can be categorized based on their (1) pharmacodynamics; (2) the subjective perceptual, psychological, and/or spiritual effect; and (3) the derived source material (see table 1).

| Table 1. Classification systems for psychedelics with select examples. | |||

| Classification | Terminology/Source | Definition | Active ingredient |

| 1. Pharmacodynamics | Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists or ‘serotonergic psychedelics’ or ‘tryptamine-based psychedelics’ or ‘classical psychedelics’ | Substances that enact on the serotonergic neurotransmitter pathway and resemble the monoamine alkaloid tryptamine.8 | Psilocybin, psilocin, LSD, DMT, 5-MeO-DMT, bufotenine (5-HO-DMT) |

| NMDA receptor antagonists or ‘dissociatives’ | Substances that distort perceptions of sight and sound and produce feelings of detachment – dissociation – from the environment and self.4 | Ketamine | |

| Amphetamine-derivative | MDMA | ||

| Psychoactive alkaloid | Ibogaine, mescaline | ||

| 2. Perceptual, Psychological, and/or Spiritual Effect | Entheogen | Substances that produce a nonordinary state of consciousness for religious or spiritual purposes and can induce an experience of “god within.”10 | Psilocybin, psilocyin, LSD, N,N-DMT, 5-MeO-DMT, 5-HO-DMT, mescaline |

| Empathogen or enactogen | A substance that produces “touching within” or emotional communion.7 | MDMA | |

| 3. Source material | |||

| Plant | Psilocybin mushrooms or ‘magic mushrooms’ | A polyphyletic category of mushrooms that contain psilocybin and psilocin. | Psilocybin, psilocin |

| Ayahuasca | Brew made from plants containing DMT and a monoamine-oxidase-like substance to permit gastrointestinal absorption of the DMT. | N,N-DMT | |

| Changa | DMT-infused smoke blend | N,N-DMT | |

| Vilca | Snuff made from the seeds of the Vilca (Anadenanthera colubrine) tree | Bufotenine (5-HO-DMT), N,N-DMT, 5-MeO-DMT | |

| ‘Peyote’ or Lophophora williamsii | Small spineless cactus native to Mexico and Texas. | Mescaline | |

| Wachuma or ‘San Pedro’ or Echinopsis pachanoi | Cactus native to the Andes Mountains | Mescaline | |

| Apocynaceae shrubs (e.g. Tabernanthe iboga) | Flowering plant native to the tropics and subtropics of Africa, Europe, Australia, and the Americas. | Ibogaine | |

| Seeds from Anadenanthera peregrina | Perennial tree native to the Caribbean and South America. | 5-MeO-DMT | |

| Animal | Parotoid secretion from Incilius Alvarius or ‘Sonoran Desert Toad’ | A toad native to northern Mexico and the Southwestern United States. | 5-MeO-DMT |

| Synthetic | Synthetically derived | MDMA, LSD, psilocybin | |

| N,N-DMT, N, N-dimethyltryptamine; 5-MeO-DMT, 5-methoxy-DMT;5-HO-DMT, 5-hydroxy-DMT; LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide; MDMA, 3,4-ethylenedioxymethamphetamine; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate | |||

Emerging research has documented a protective role of psychedelics in the management of major depressive disorder, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, cancer-related existential crisis, and substance (i.e. nicotine, alcohol, and narcotic) use disorders, particularly as an adjuvant to psychotherapy.4-9 These early studies have consistently called for further investigation; however, uniformly conclude that psychedelics appear to be effective in managing these conditions and are generally well tolerated in research settings.5-7,9

Moreover, early studies have examined the impact of psychedelics on life-satisfaction and their ability to induce ‘mystical-type’ experiences in healthy populations and suggest that psychedelics have the ability to enhance life-satisfaction, subjective well-being, and induce mystical-type or so-called “quantum change/psychologically transformative” experiences.11,12 With the resurgence of interest in psychedelics, ongoing risk profiling of these substances must continue in both research and real-world settings.

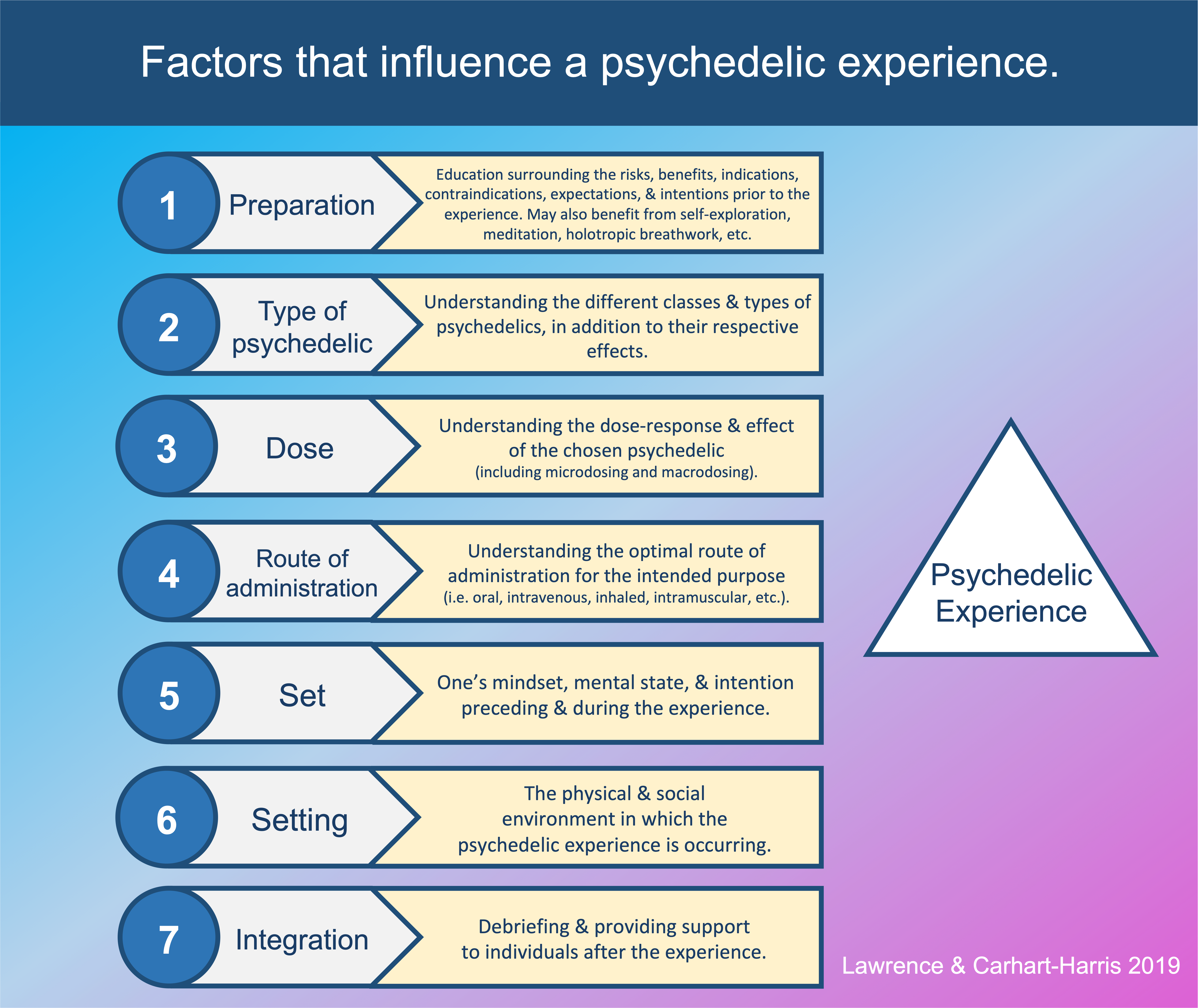

The pharmacological, perceptual, and therapeutic effects that psychedelics induce depend upon: (1) preparation; (2) the type of psychedelic; (3) route of administration; (4) the dose (including macro- versus microdosing13); (5) the set and (6) setting in which the drug is administered; and (7) integration following the experience (see infographic). The ‘set’ (referring to one’s mindset, mental state, and intention preceding and during the experience) and the ‘setting’ (referring to the physical and social environment in which the psychedelic experience is occurring) greatly influence the trajectory of the experience. 8

The majority of psychedelics enact their properties via serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonism (i.e. ‘serotonergic psychedelics’ or ‘classical psychedelics’)8 and include: psilocybin and psilocin (the active ingredients in psilocybin or “magic” mushrooms); N, N-dimethyltryptamine or ‘DMT’ (the active ingredient in Ayahuasca and Changa); 5-methoxy-DMT or ‘5-MeO-DMT’ (secreted from the parotoid glands of the Incilius Alvarius toad and certain plant-species); bufotenin or ‘5-HO-DMT’; and lysergic acid diethylamide or ‘LSD.’ Additional psychoactive agents can induce psychedelic experiences including NMDA receptor antagonists (i.e. ‘dissociatives’), amphetamine-derivates, and psychoactive-alkaloids.7

Psychedelics are receiving increased research and media attention and have demonstrated early therapeutic benefit in managing a multitude of mental health conditions. 4-8 Evidence suggests these tools should not be used or studied in isolation, but as an adjuvant to psychotherapeutic practices to support mental resilience, in additional emotional and experiential acceptance.8 Sports medicine practitioners should become aware of psychedelic agents and the developing field of research examining their role in the management of mental health and wellbeing. In the future, psychedelics may be an additional avenue to explore to manage not only mental health conditions in the athletic population, but also sport-specific stressors including burnout, retirement and life transitions, and sporting failure.2

***

Dr. David Lawrence (@davidwlawrence1) is an academic sports medicine physician in Toronto, Canada with privileges at the David L. MacIntosh Sport Medicine Clinic (Faculty of Kinesiology & Physical Education, University of Toronto), Mount Sinai Hospital (Sinai Health Systems), and the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute (University Health Network). Email: dw.lawrence@mail.utoronto.ca

Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris (@RCarhartHarris) is the Head of the Centre for Psychedelic Research, Division of Brain Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- Bauman NJ. The stigma of mental health in athletes: are mental toughness and mental health seen as contradictory in elite sport? British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016;50(3):135-136.

- Arnold R, Fletcher D. A research synthesis and taxonomic classification of the organizational stressors encountered by sport performers. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology. 2012;34(3):397-429.

- Gouttebarge V, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Gorczynski P, et al. Occurrence of mental health symptoms and disorders in current and former elite athletes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine. 2019;53(11):700-706.

- Tracy DK, Wood DM, Baumeister D. Novel psychoactive substances: types, mechanisms of action, and effects. Bmj. 2017;356:i6848.

- Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Rucker J, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(7):619-627.

- Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181-1197.

- Mithoefer MC, Grob CS, Brewerton TD. Novel psychopharmacological therapies for psychiatric disorders: psilocybin and MDMA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(5):481-488.

- Johnson MW, Hendricks PS, Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Classic psychedelics: An integrative review of epidemiology, therapeutics, mystical experience, and brain network function. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;197:83-102.

- Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(2):399-408.

- Godlaski T. The god within. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46:1217-1222.

- Griffiths RR, Richards WA, McCann U, Jesse R. Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2006;187(3):268-283; discussion 284-292.

- Uthaug MV, Lancelotta R, van Oorsouw K, et al. A single inhalation of vapor from dried toad secretion containing 5-methoxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine (5-MeO-DMT) in a naturalistic setting is related to sustained enhancement of satisfaction with life, mindfulness-related capacities, and a decrement of psychopathological symptoms. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2019;236(9):2653-2666.

- Polito V, Stevenson RJ. A systematic study of microdosing psychedelics. PloS one. 2019;14(2):e0211023.