Written by Gráinne Donnelly with input from Emma Brockwell and Tom Goom

More people than ever run today, and it’s likely because of the increasing number of girls and women that now run too (Lynch and Hoch 2010). For many women, whether training for leisure or competition, running has the benefits of efficient physical fitness, a leaner body composition, and a chance to get some well-earned headspace or socialize.

Running after pregnancy

There are important factors to consider before returning to running after having a baby. Are you aware of the potential risk factors for pelvic floor dysfunction? This happens if a mother does not rehabilitate adequately before she returns to high impact exercise. It’s a topic that is still underestimated and misunderstood in today’s health and fitness world. We are all familiar with the importance of injury recovery and rehabilitation, including optimal loading at optimal time frames. We wouldn’t consider returning a footballer to play following a grade 2 ligament sprain or an ACL injury until they had made appropriate progression through rehabilitation, satisfied specific ‘return to play criteria’ and were assessed to be ‘match ready’, and consensus statements help to guide this (Adern et al.2016). Why then, do we not consider the huge physical and mental implications that pregnancy and childbirth impart on a woman prior to giving the thumbs up to exercise?

Postnatal women returning to running: a guideline

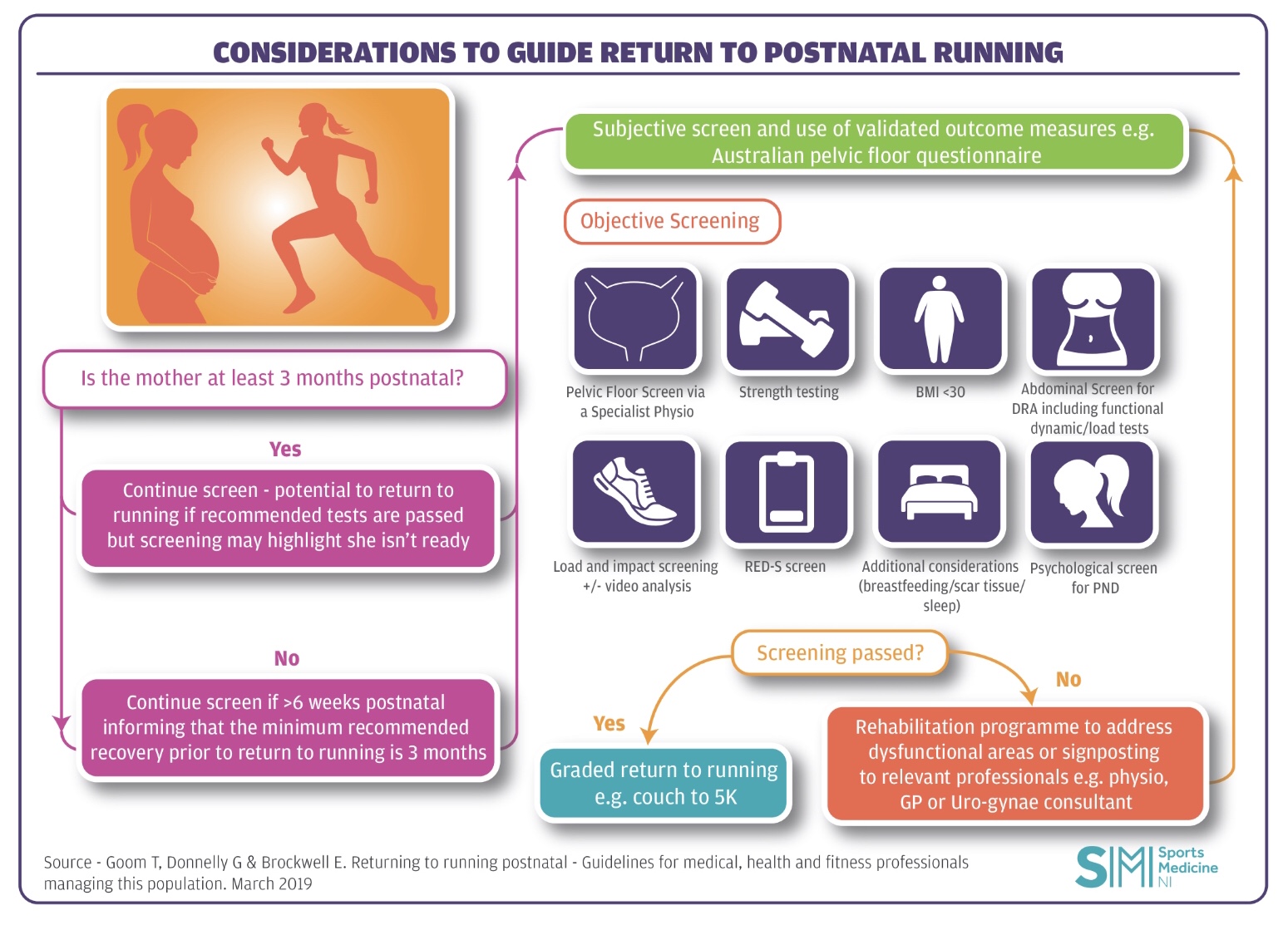

March 2019 saw the release of the first ever UK guideline to specifically offer evidence based recommendations for postnatal women returning to running – “Returning to running postnatal – guidelines for medical, health and fitness professionals managing this population”(Goom, Donnelly & Brockwell 2019). You can check out the full guideline here.

About pelvic health

Many reading this may not be familiar with pelvic health and all the terminology that goes alongside it. To provide a brief background, pelvic health is an important to consider for all health and fitness professionals managing women and refers to the function and wellbeing of the muscles, organs, nerves and connective tissue in the pelvic region. It involves much more than just advising Kegel’s.

Between 15-30% of first time mums will experience urinary incontinence (Milsomet al.2014) and a startling 1 in 5 first time mums complain of faecal incontinence at 1 year postnatal, especially if they demonstrated symptoms during pregnancy (Johannessen et al. 2014). At 3-6 months postnatal up to 56% of new mothers demonstrate grade 2 or more pelvic organ prolapse (Bø et al. 2017). This means that one or more of the pelvic organs (bladder, bowel or uterus) have descended downwards into the vagina to at least the vaginal opening.

What changes happen to the pelvic region during and after pregnancy?

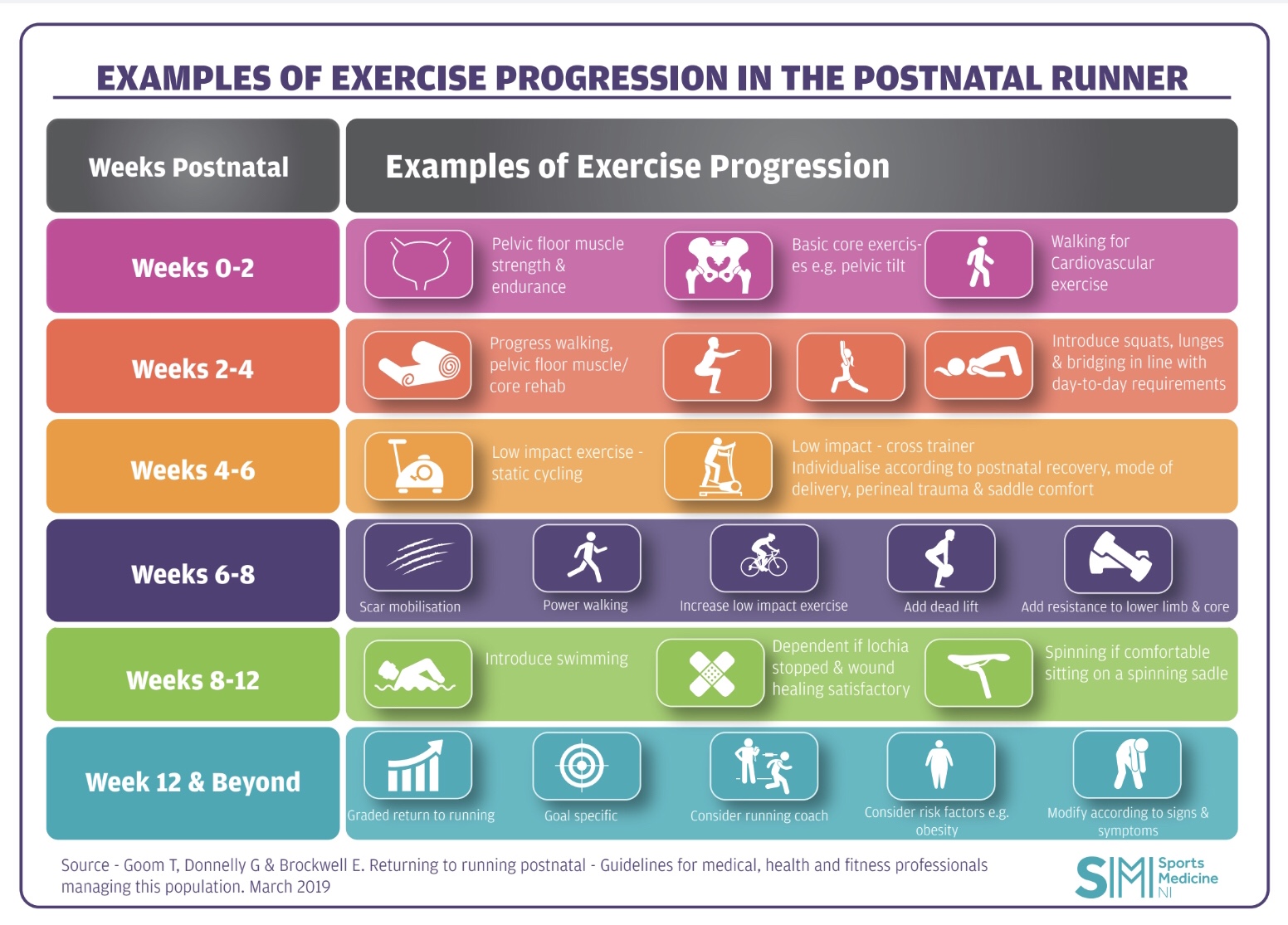

To give further insight into the impact pregnancy and delivery have on a woman’s body it’s important to understand the changes that occur in the pelvic region. The levator hiatus widens during pregnancy and increases significantly during vaginal birth. Recovery time for the tissues is understood to be between 4-6 months (Shek et al.2010, Stær-Jensen et al. 2015), well beyond the traditional concept of full recovery by the 6-week postnatal check. To reinforce this, if we consider caesarean section deliveries, we understand that abdominal fascia has only regained just over 50% of original tensile strength by 6-weeks post abdominal surgery and 73%-93% of original tensile strength by 6-7 months (Ceydeli et al.2005). Pelvic health physiotherapists around the world are passionate about raising awareness of the extended recovery period that is actually needed. Often for litigation purposes, the 6-week milestone is one that serves as a tick box confirming readiness and suitability to return to an exercise class, sporting activity or elite training. The healing process, however, extends well beyond this, and it is essential that the narrative on this subject changes and adapts to better serve our sporting women. Let’s change the focus from one that limits the parous, sporting generation (treating issues after they present) to one that understands, empowers and safeguards women to protect their pelvic health (preventing/limiting common but not normal issues occurring in the first place). This in turn is likely to have a positive impact on their ability to sustain sporting activities in the long-term. We need to start giving pregnancy and childbirth the same level of consideration for recovery that we do for ligament, tendon, nerve and muscle injuries around the body. The guideline recommends that postnatal women wait until at least 12 weeks prior to planning a return to running. This timescale is advised as a guide rather than prescriptive cut off.

Mothers can also develop Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S)

Of course, like any injury or recovery approach, healing after childbirth is not simply about timescales. There are a multitude of factors that play an important role in a woman’s recovery including sleep, nutrition, breastfeeding, weight and psychological status. The risk of a postnatal mother developing Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) should not be overlooked. RED-S, formerly known as the Female Athlete Triad, refers to an energy deficiency relative to the balance between dietary energy intake and the energy expenditure required to support homeostasis, health and the activities of daily living, growth and sport (Mountjoy et al.2014). It affects many aspects of physiological function including metabolic rate, menstrual function, bone health, immunity, protein synthesis, cardiovascular and psychological health. With the lifestyle change that a new mother faces (including sleep deprivation, lack of routine, demands of breastfeeding and the potential to alter eating habits), it isn’t hard to foresee how an energy deficiency may occur. On top of that, many sporting athletes feel pressured to get back into training and return to their prenatal physique which may further influence choices predisposing risk factors to RED-S. For more information on RED-S check out this recent blog (Dudgeon 2019).

The key message from the new guideline: all postnatal women, regardless of delivery mode, should be assessed by a pelvic health physiotherapist prior to returning to high impact sport. Any signs or symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction indicates further or ongoing assessment and management prior to continuing and progressing training. Key load and impact management testing is outlined in the guideline to expose a postnatal woman to high impact exercise and monitor for signs and symptoms of musculoskeletal and/or pelvic floor dysfunction. Common signs and symptoms include leaking urine or faeces, heaviness/dragging in the pelvic area, pain with intercourse, obstructive defecation, abdominal separation compromising abdominal function or lumbopelvic pain that exists before, during or after running.

The guide encourages health and fitness professionals to work together across the traditional boundaries of specialism to give a more holistic approach to postnatal recovery. It applies across many roles from sports and exercise medicine physicians and musculoskeletal physiotherapists to coaches and trainers working together with pelvic health physiotherapists to evaluate overall readiness for return to running.

***

Grainne Donnelly @ABSPhysio is the Advanced Physiotherapist and Team lead for Pelvic Health in Western Health and Social Care Trust Website in Northern Ireland and works in private practice.

Infographics with thanks to @SportsMedNI

ACPSEM Blog Co-Ordinator: @helenmcelroy

References

Ardern, C., Glasgow, P., Schneiders, A., Witvrouw, E., Clarsen, B., Cools, A., Gojanovic, B., Griffin, S., Khan, K., Moksnes, H., Mutch, S., Phillips, N., Reurink, G., Sadler, R., Grävare Silbernagel, K., Thorborg, K., Wangensteen, A., Wilk, K. and Bizzini, M. (2016). 2016 Consensus statement on return to sport from the First World Congress in Sports Physical Therapy, Bern. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(14), pp.853-864.

Bø, K. Artal, R., Barakat, R., Brown, W. J., Davies, G. A. L., Dooley, M., Evenson, K. R., Haakstad, L. A. H., Kayser, B., Kinnunen, T. I., Larsénm K., Mottola, M. F., Nygaard, I., van Poppel, M., Stuge, B., Khan, K. M. (2017) Exercise and pregnancy in recreational and elite athletes: 2016/17 evidence summary from the IOC Expert Group Meeting, Lausanne. Part 3-exercise in the postpartum period. Br J Sports Med 51(21), pp.1516-1525.

Ceydeli, A., Rucinski, J. and Wise, L. (2005) Finding the best abdominal closure: an evidence-based review of the literature. Curr Surg 62, pp.220–5.

Dudgeon, E. (2019). Relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): recognition and next steps. [Blog] BJSM. Available at: https://blogs.bmj.com/bjsm/2019/04/22/relative-energy-deficiency-in-sport-red-s-recognition-and-next-steps/ [Accessed 25 Apr. 2019].

Goom, T., Donnelly, G. and Brockwell, E. (2019) Returning to running postnatal – guideline for medical, health and fitness professionals managing this population. [https://mailchi.mp/38feb9423b2d/returning-to-running-postnatal-guideline]

Lynch, S. and Hoch, A. (2010). The Female Runner: Gender Specifics. Clinics in Sports Medicine, 29(3), pp.477-498.

Milsom, I., Coyne, K., Nicholson, S., Kvasz, M., Chen, C. and Wein, A. (2014). Global Prevalence and Economic Burden of Urgency Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review. European Urology, 65(1), pp.79-95.

Mountjoy, M., Sundgot-Borgen,, J., Burke,, L., Carter, S., Constantini, N., Lebrun, C., Meyer, N., Sherman, R., Steffen, K., Budgett, R., Ljungqvist, A. (2014) The IOC consensus statement: beyond the Female Athlete Triad—Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S) Br J Sports Med 48, pp.491–497. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-093502.

Shek, K. and Dietz, H. (2010). Intrapartum risk factors for levator trauma. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 117(12), pp.1485-1492.

Stær-Jensen, J., Siafarikas, F., Hilde, G., Benth, J.Š., Bø, K. and Engh, M.E. (2015) Postpartum recovery of levator hiatus and bladder neck mobility in relation to pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 125, pp.531–539.