Start with Part 1 of this blog here.

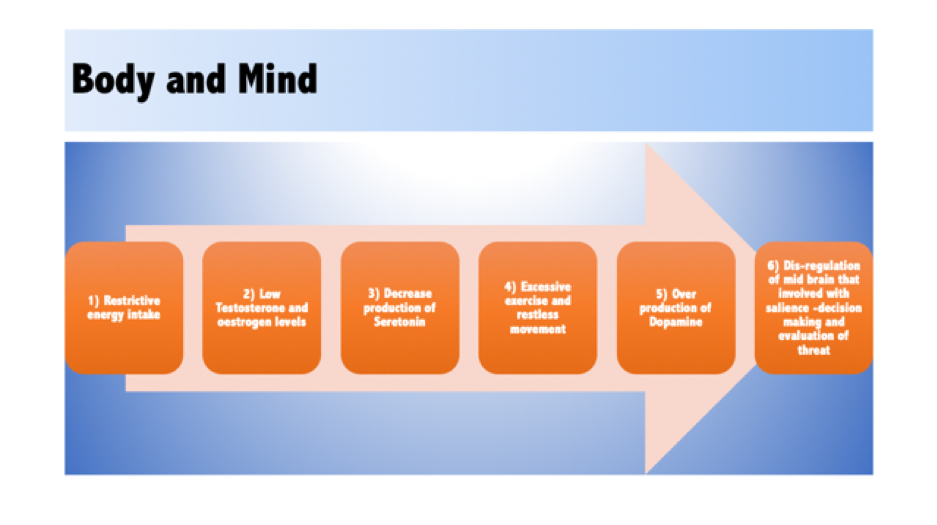

Physically, when the body is under “stress” levels of cortisol rise. When this is chronic, it prevents the pituitary gland from working effectively, leading to hormonal disturbances that have serious negative consequences.(1-3) The more obsessive and restrictive an athlete becomes, the more the workings of neurotransmitters are affected, which in turn structurally affects the brain. In addition to this, there is a heightened sense of anxiety, which leaves an individual feeling physically and mentally uncomfortable. In an attempt to control and contain these emotions, the individual’s behaviours become even more rigid and controlled.(4)

The importance of self acceptance and how to achieve it

Emotional problems need to be dealt with. A lack of self worth and ability to believe you are good enough develops through a number of different means –your experiences, your interpretations of situations and your personality type. In order to be able to navigate through life, you have to learn accept yourself and I would highly recommend working with a clinical psychologist trained in this field. So many of us allow our circumstances to define who we are and yet just because you didn’t achieve a podium finish, does that really make you a failure or a bad person? Of course not, you are still you, the same you, you were a few days earlier, and the person that may have been flying in a training session last week.

So what’s involved in the road to “recovery”. Well first let’s look at the term “recovery”. An eating disorder is a part of you– it is that perfectionist side of you that has gone into overdrive and never lets you rest or believe you are enough. Awareness of this is the first step, because understanding this helps you to then appreciate that it is something you need to learn to challenge. After this, “recovery” is possible because its about managing your expectations, however, it is also highly possible that at time of high stress and anxiety, when life “feels” chaotic, your default coping mechanism will be to once again restrict and “contain”.(5)

The multi-disciplinary team approach

To get the best chance of “recovery” for the athlete, I choose to work in a multi-disciplinary team. The team should comprise of medic, a clinical psychologist, a specialist dietitian and I also like to work with an endocrinologist so we can test and monitor biomarkers that give us information on physical status. It’s important to highlight the importance of clinical practitioners here in both psychology and nutrition. Dietitians are the only nutritional practitioners regulated and trained to work in clinical areas such as Eating Disorders and RED-s.(6)

One of the key aspects of recovery is to restore weight (if the athlete is underweight) but also regulate their hormones. This can be achieved through a process of mechanical eating where the athlete needs to eat at regular intervals regardless of how they might “feel”. While many athletes will want to learn how to “eat intuitively” this will not be possible until hormones and biochemistry return to and remain consistently in a normal range. At this stage hunger cues may finally return.

My practise involves working through a number of tasks, both nutritional and behavioural. I help the athlete challenge their behaviours but also create a tool kit that they can continue to use so that they return back to their sports as a more resilient robust athlete both physically and mentally.

Building physically and mentally robust athletes

“The key to our wellbeing is not low expectations. It is the ability to interpret unexpected negative outcomes in a positive way. We should look at failure as an opportunity to learn and do better, and bask in our high expectations”.(7)

References

- Keay et al. Bone mineral density in professional female dancer, BJSM, 2016

- Keay et al.Low energy availability assessed by a sport-specific questionnaire and clinical interview indicative of bone health, endocrine profile and cycling performance in competitive male cyclists, BJSM, 2018

- Burke et al. Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport in Male Athletes: A Commentary on Its Presentation Among Selected Groups of Male Athletes. IJSNEM, 2018.

- McGregor, R. Why Do Athletes use Food and training as a Means of Coping. Presentation to Sport Wales, 2019.

- Flett and Hewitt. The Perils of Perfectionism in Sports and Exercise, CURRENT DIRECTIONS IN PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE, 2005.

- Joy, EB et al. Update On Eating Disorders In Athletes. A comprehensive narrative review with a focus on clinical assessment and management. BJSM, 2016: https://edinstitute.org/paper/2012/11/23/phases-of-recovery-from-an-eating-disorder)

- Should You Manage Your Expectations? A lesson about optimism from the 2012 London Olympics. Posted Jul 29, 2012 – original quote, George Loewenstein (1987)

**

Renee @mcgregor_renee is a Sports and Eating disorder specialist Dietitian who works with a number of NGBs, Coaches, professional athletes and sports science teams to provide nutritional strategies to enhance sport performance and manage eating disorders. She has an undergraduate in Biochemistry, a post graduate in Dietetics, a further postgraduate in Applied Sports Nutrition and is currently working towards a post graduate in mental health and neuroscience psychology. Email: rm@reneemcgregor.com

Renee works collaboratively with Nicky Keay, Consultant Sports Endocrinologist and they are excited to announce the opening of the EN:SPIRE clinic in Bath 10thApril. EN:SPIRE is the UK’s first Sport and Dance RED-s, Overtraining and Eating Disorder Specific recovery clinic.