By Drs Anne Benjaminse @AnneBenjaminse and Alli Gokeler @AlliGokeler

Owoeye and colleagues correctly addressed the concern of adherence to injury prevention programmes as key to achieve a societal health impact: ‘it takes more than just a prescription and education to get patients to take their drugs’.1 In order to be effective in the real world, uptake of the programme must be guaranteed.1-4 Currently, coaches and athletes use injury prevention programmes designed by researchers, however, uptake has been low to date seen by the continuous rise of ACL injuries per 1000 athlete-exposures.5 But, why is uptake low? Often times, we see that trainers and coaches hesitate to implement prevention exercises or even stop the proposed program,6-10due to a lack of 1) facilities/resources, 2) leadership/knowledge, 3) player enjoyment/engagement, or 4) training time/link to training goals.10 Some athletes find that prevention exercises ‘take too long’, are ‘boring’, ‘have no performance benefits’ or ‘are too difficult’. As a follow up on previous work by Owoeye et al., we would like to contribute innovative ideas on how to optimize adherence to injury prevention programmes.

Advancing adherence by co-creation

First, we propose that when designing injury prevention programs, the end-users (trainers, coaches, athletes, club board, parents) are involved from the beginning.3, 11By recognizing the end-users and their beneficiary needs through co-creation, the intervention can be tailor-made to suit their needs. For long-term implementation, co-creation and a ‘train-the-trainer’ approach should be used to have the end-users consider the program as their own,12 which is also supported by the culture of the club.

One solution is to develop an athletic skill program that entails elements to improve athlete’s performance (eg, shot accuracy or changing direction as quickly as possible) as well as reduce some intrinsic risk factors for injury (eg, how athlete lands after shot or how athlete conducts the cutting movement). In other words, enhancing athletic skills of athletes in a challenging, fun, interactive, motivational and sport specific context.

Optimal motor learning – triple play

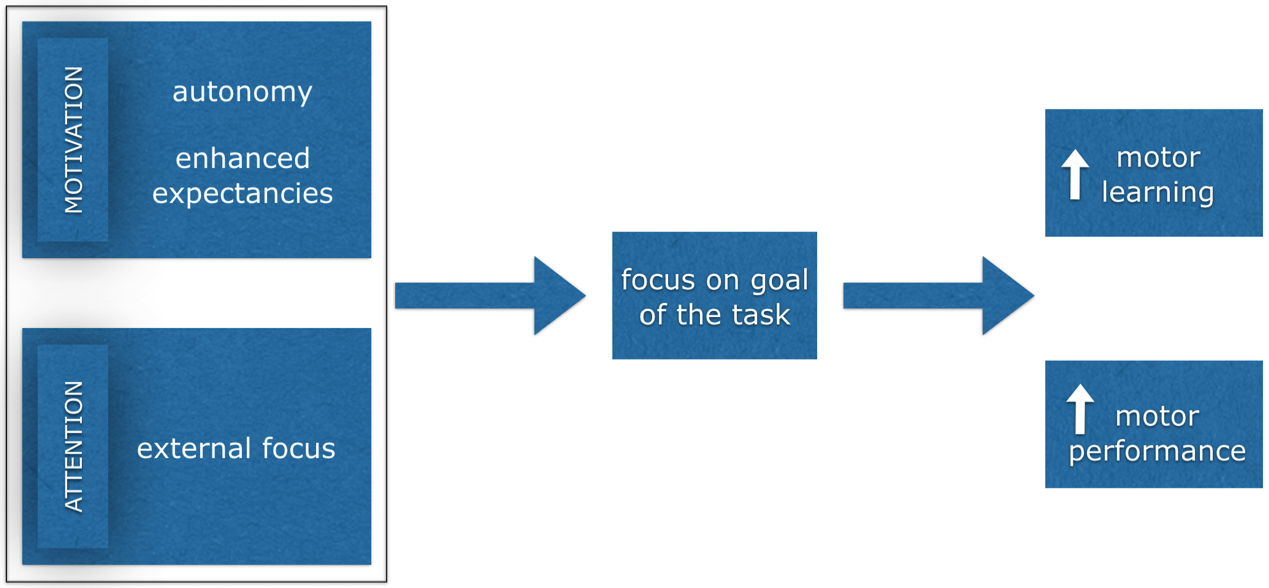

Second, an athlete’s ability to create stable motor output in a complex athletic environment and avoid an injurious situation during sport specific activities is key in injury prevention. To optimise the potential of motor learning, Wulf et al. propose the following model (Figure 1),13where (1) applying an external focus of attention and promoting intrinsic motivation by (2) autonomy and by (3) creating enhanced expectancies, will increase goal action coupling.

Advancing adherence by increasing retention

External focus of attention

With even relatively short training sessions, applying an external focus of attention (bottom part of the model, Figure 1) enhances learning movement patterns efficiently with high retention (ie, sustained effects over time).13-15 These findings show that a barrier such as ‘it takes too long’ could be countered when implementing a visual or verbal external focus of attention. The high retention means that the athletes may only need periodic maintenance (ie, is less time consuming) on a certain skill as a result of effective stimulation used to learn skills.

Advancing adherence by paying attention to basic psychological needs

Third, to increase adherence, we propose that attention is given to basic psychological needs of the athletes. This includes: 1) autonomy and 2) creating enhanced expectancies (ie, increasing feeling of competence) when implementing the injury prevention programme enhances intrinsic motivation (top part of the model, Figure 1).

Autonomy

Allowing athletes a certain extent of self-control over a practice condition can facilitate feelings of autonomy and competence, thereby fulfilling some fundamental psychological needs.16This in turn will enhance intrinsic motivation and internalisation,16 which is crucial for advancing adherence in injury prevention. When exercising, autonomy should be supported by providing the athletes with simple, but crucial, choices.13,17,18For example, this can be 1) task difficulty, 2) the practice material to exercise with, 3) when to receive feedback and 4) what type of feedback to receive (eg, verbal or visual or a combination, self-model or expert-model). At all times, the expert’s view and expertise is necessary. As an expert, always pay attention to safety and difficulty. That is, take care of the fact that an athlete picks an exercise that is challenging (learning effect), but not too difficult (safety). In addition, consider how many choices you will provide during a practice session.

For each aspect of choice, an example is given below:

Ad. 1:To improve the capacity of an athlete to change direction quickly, an athlete can choose from three practice conditions:

- In a square with a buddy, touching one of the four cones, where the athletes has to follow the buddy (social interaction and decision making included, but relatively small movements).

- Sidestep cutting situation can be practiced with a 5m sprint, changing direction, followed by 5m sprint (more pressure on performance, greater on-field movement, but anticipated).

- The same a sidestep cutting situation can be practiced with a 5m sprint, catching a ball which is thrown by a buddy at the turning point, changing direction, followed by 5m sprint (pressure on performance, greater on-field movement, unanticipated and attention has to be payed to the environment).

Ad. 2: When an athlete has chosen the third option of Ad 1. The choice can be given on what type of ball to practice with (ie, tennis ball, handball, basketball).

Ad. 3: Let the athlete choose when to receive feedback from the expert (trainer, coach, sport physical therapist) and/or what type of feedback to receive. This helps the athlete to stay in the flow of practicing and not being potentially interrupted.

Ad. 4:When the athlete indicates he/she wants to receive feedback, it is good to have several options available the athlete can choose from, picking an option that the athlete thinks is most valuable for the learning process at that time. For example, verbal external focus feedback or watching a self- or expert video of a given task.15, 19

Enhanced expectancies

Circumstances that enhance learners’ expectations and increase confidence, increase movement automaticity. The athlete will no longer have to worry about task execution, but can focus on the goal of the task. Providing positive feedback or reducing experienced task difficulty can alleviate learners’ concerns and increase perceptions of competence and self-efficacy.13,20,21In this context, it is of importance to note that athletes tend to request feedback after good trials. Coaches are encouraged to provide positive feedback to confirm competence, self-efficacy and enhancing intrinsic motivation.22

***

Competing interests

AB and AG report no conflicts of interest.

Anne Benjaminse is a post doctoral researcher at the Center for Human Movement Sciences, University Medical Center Groningen, University of Groningenand School of Sport Studies, Hanze University Groningen, Groningen, The Netherlands. Email: a.benjaminse@umcg.nl

Alli Gokeler is an ESSKA and GOTS board member. He is currently postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Neuroscience in Sports and Exercise, Institute of Sports Medicine, University of Paderborn, Germany. In addition, he is head clinical knowledge transfer at the Luxembourg Institute of Research in Orthopeadics, Sports Medicine and Science, Luxembourg, Luxembourg

References

- Owoeye OBA, McKay CD, Verhagen EALM, et al. Advancing adherence research in sport injury prevention. Br J Sports Med2018;52:1078-79.

- McKay C, Steffen K, Romiti M, et al. The effect of coach and player injury knowledge, attitudes and beliefs on adherence to the FIFA 11+ programme in female youth soccer. Br J Sports Med2014;48:1281-86.

- Donaldson A, Lloyd DG, Gabbe BJ, et al. We have the programme, what next? Planning the implementation of an injury prevention programme. Injury prevention : journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention

- McKay CD, Verhagen E. ‘Compliance’ versus ‘adherence’ in sport injury prevention: why definition matters. Br J Sports Med2016;50:382-3.

- Agel J, Rockwood T, Klossner D. Collegiate ACL Injury Rates Across 15 Sports: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System Data Update (2004-2005 Through 2012-2013). Clin J Sport Med2016;26:518-23.

- Myklebust G, Bahr R. Alarming increase in ACL injuries among female team handball players after the end of successful intervention study: a 2 year follow up. Br J Sports Med2005;39:382–83.

- Steffen K, Myklebust G, Olsen OE, et al. Preventing injuries in female youth football–a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports2008;18:605-14.

- Bahr R, Thorborg K, Ekstrand J. Evidence-based hamstring injury pre- vention is not adopted by the majority of champions league or norwegian pre- mier league football teams: the nordic hamstring survey. Br J Sports Med2015;49:1466–71.

- O’Brien J, Young W, Finch CF. The delivery of injury prevention exercise programmes in professional youth soccer: Comparison to the FIFA 11. J Sci Med Sport2017;20:26-31.

- Donaldson A, Callaghan A, Bizzini M, et al. A concept mapping approach to identifying the barriers to implementing an evidence-based sports injury prevention programme. Injury prevention : journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention

- O’Brien J, Finch CF. Injury Prevention Exercise Programs for Professional Soccer: Understanding the Perceptions of the End-Users. Clin J Sport Med2017;27:1-9.

- Padua DA, Frank B, Donaldson A, et al. Seven steps for developing and implementing a preventive training program: lessons learned from JUMP-ACL and beyond. Clin Sports Med2014;33:615-32.

- Wulf G, Lewthwaite R. Optimizing performance through intrinsic motivation and attention for learning: The OPTIMAL theory of motor learning. Psychon Bull Rev2016;23:1382-414.

- Benjaminse A, Otten E. ACL injury prevention, more effective with a different way of motor learning? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc2011;19:622-7.

- Benjaminse A, Otten B, Gokeler A, et al. Motor Learning Strategies in Basketball Players and its Implications for ACL Injury Prevention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc2017;25:2365-76.

- Sanli EA, Patterson JT, Bray SR, et al. Understanding Self-Controlled Motor Learning Protocols through the Self-Determination Theory.Front Psychol2013;3.

- Lewthwaite R, Chiviacowsky S, Drews R, et al. Choose to move: The motivational impact of autonomy support on motor learning. Psychon Bull Rev2015;22:1383-8.

- Wulf G, Lewthwaite R, Cardozo P, et al. Triple play: Additive contributions of enhanced expectancies, autonomy support, and external attentional focus to motor learning. Q J Exp Psychol (Hove)2017:1-9.

- Benjaminse A, Gokeler A, Dowling AV, et al. Optimization of the anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention paradigm: novel feedback techniques to enhance motor learning and reduce injury risk. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther2015;45:170-82.

- Badami R, VaezMousavi M, Wulf G, et al. Feedback after good trials enhances intrinsic motivation. Res Q Exerc Sport2011;82:360–64.

- Badami R, VaezMousavi M, Wulf G, et al. Feedback about more accurate versus less accurate trials: Differential effects on self-confidence and activation. Res Q Exerc Sport2012;83:196–203.

- Saemi E, Porter JM, Ghotbi-Varzaneh A, et al. Knowledge of results after relatively good trials enhances self-efficacy and motor learning. Psychol Sport Ex2012;13:378-82.