By Paul Blazey @blazey85

To coincide with the start of today’s Ryder Cup, this week BJSM published the 2018 consensus statement on golf and health (1). In the paper, golf is portrayed as a means to address current public health concerns over a lack of physical activity, and as a sport with health benefits as well as risks.

Risks? In golf? Yes, they exist. Primarily due to increased sun exposure associated with playing golf.

The consensus brings together leading experts to advise and the message is not just relevant to golf but can be more broadly applied to the physical activity benefits of participation in any sport of moderate intensity. The lack of physical activity in westernised society often goes under-reported as people tend over-estimate their levels of physical activity. This is why WHO produced the Global Action Plan on Physical Activity (GAPPA) (2).

In a multi-country study – the IPEN study – walkability was portrayed as a major determinant in people’s physical activity within their home area (3). Golf and the natural settings within which it takes place can provide an excellent option in any clinician’s toolkit to encourage greater activity for patients across their lifespan. This is especially true of those who see sports as either a ‘younger person’s activity’ or have existing co-morbidities that may affect their capacity for higher levels of physical exertion.

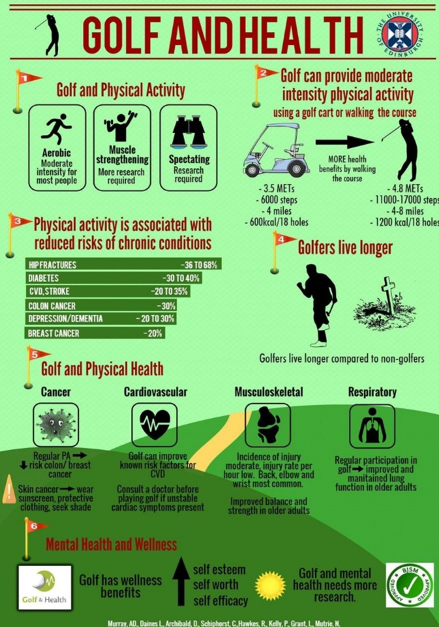

The 2017 scoping review carried out by Murray et al (4) is available FREE to access here. It set out some of the key benefits of participation in golf that clinicians can use to educate patients. These are neatly summarised by the infographic included below.

Key challenges to implementation do exist, including societal perceptions of golf as a sport for the middle-class. There is a healthy population of active golfers numbering 60 million (defined as 2 separate golfing participations within the past 12 months) according to the report. However, an over-representation of those with a white European ethnic background still exists, in spite of the enduring ‘Tiger Woods effect’. There is also a pre-dominance of males compared with females (5-7). Neither of these factors are insurmountable with clubs becoming more welcoming to participants across the spectrum. Clinicians who foster connections with local clubs may be able to better support their patients to find accessible routes in to the sport.

These challenges will not be addressed overnight. Changing the societal impressions of golf may be a generational target. It will involve the policy makers using levers to increase the appeal and access to short forms of the game (e.g. ‘pitch and putt’ or adventure golf) courses that provide physical activity within a reduced time commitment, often cited as a potential barrier to participation. Clinicians can use this release to support discussion within their own spheres of influence to help speed up the implementation process.

Some of the key actions for policy/decision makers are highlighted in the infographic produced to support the release of the consensus statement included here.

Green spaces and mental health

The statement also outlines how golf can improve mental health, and foster cognitive, social and functional benefits. Golf can be seen as a ‘green exercise’ that increases a connection with nature and support mental wellbeing. The direct causation of benefits from being in nature have yet to be proven but the evidence linking access to green space with increased physical activity is growing (8). The reduction in public greenspaces, especially around urban areas, means golf courses may provide the best kept access to greenery within urban environments. The consensus statement quite rightly points out that courses could include multi-purpose facilities. Options may include opening up better walking routes for the general public to gain access to some of the course areas and increasing both their exposure to a naturalistic setting as well as the game itself by association.

A recent edition of the BJSM published several new reviews, original research and editorials that focused on walking as a ‘Man’s best medicine’, and a key determinant in long term health and wellbeing (9). Walking benefits associated with golf can be added to research focused on the elderly, showing golf specifically improved balance outcomes that reduce the risk of falls (10-12). Given the long-term health risks associated with falls, this is a particularly important finding for clinicians to consider when supporting healthy lifestyles into older age.

High quality research is still needed to consolidate the relationships between golf and mental health and well-being, the contribution of golf to muscle strength and balance, benefits to particular populations, and to explore the cause and effect nature of associations between golf and health.

The lessons learned from this consensus are not just for those who work within and play golf. They are an opportunity for all health professionals to encourage greater physical activity for their patients. Golf can improve patient education and offers another potential source of physical activity to add to the toolkit of options that encourage lifelong healthy behaviours.

References

- Murray AD, Archibald D, Murray IR, et al. International Consensus Statement on Golf and Health to guide action by people, policymakers and the golf industry. Br J Sports Med. (2018) Published Online First: 23 September 2018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099509

- World Health Organisation. More active people for a healthier world. The global action plan on physical activity 2018-2030. World Health Organisation. 2018.

- Adams MA, Frank LD, Schipperijn J, et al; International variation in neighborhood walkability, transit, and recreation environments using geographic information systems: the IPEN adult study. International Journal of Health Geographics. (2014) 13:43. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-072X-13-43

- Murray AD, Daines L, Archibald D, et al. The relationships between golf and health: a scoping review. Br J Sports Med (2017) 51, 12-19.

- The R&A. Annual review 2016. The R&A Online. 2017.

- KPMG Golf Advisory Practice. Golf Participation in Europe 2017. KPMG report. 2017.

- National Golf Foundation. Golf participation in the US summary. National Golf Foundation Summary Reports. 2017.

- Rosella Saulle, Giuseppe La Torre; Good quality and available urban green spaces as good quality, health and wellness for human life, Journal of Public Health (2012) 34:1, 161–162. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdr090

- Stamatakis E, Hamer M, Murphy MH. What Hippocrates called ‘Man’s best medicine’: walking is humanity’s path to a better world. British Journal of Sports Med (2018) 52, 753-754. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099371

- Tsang WW, Hui-Chan CW. Static and dynamic balance control in older golfers. J Aging Phys Act. (2010) 18, 1–13.

- Tsang WW, Hui-Chan CW. Effects of exercise on joint sense and balance in elderly men: Tai Chi versus golf. Med Sci Sports Exerc (2004) 36, 658–67.

- Gao K, Hui-Chan C, Tsang W. Golfers have better balance control and confidence than healthy controls. European Journal of Applied Physiology. (2011) 111:11. 2805-12.