Swiss Junior Doctors and Undergraduate Perspective on Sport and Exercise Medicine Blog Series

By Giulia Marzano and Justin Carrard, @MarzanoGiuli, @Carrard.Justin

“I am very sorry to tell you that you suffer have bowel cancer (…). But we are able to treat this kind of cancer with pretty good results. Treatment consists of surgery as well as chemotherapy and regular physical activity (…). The best training program includes 5 times 30 minutes of moderate intensity activity and twice weekly strength training. I can direct you to a specialist in adapted physical activity who will support you to meet these targets.”

This might seem like science fiction to a lot of health practitioners. However, it is now widely accepted that physical activity has positive effects on preventing a lot of cancers. Growing evidence shows that exercise can also be helpful during and after cancer treatment (2).

This is the first of 3 blogs about exercise oncology. In this first one, we review current evidence on prevention and treatment of oncological diseases.

Exercise… to prevent cancer

Sedentary behaviour increases cancer risk (1,2). According to a British study, about 1% of all cancer in the UK are attributable to low physical activity level. This corresponds to 34 000 cases per year (3). The three most studied cancer types related to physical activity are breast, colon and endometrial cancers.

In a meta-analysis of 31 studies, most active women had a 12% lower risk of developing breast cancer that the least active women (4). Concerning colon cancer, meta-analyses suggest a 25% lower risk for the most active groups (5,6). Lastly, active women have apparently a 30% decreased risk to suffer from endometrial cancer (7).

A meta-analysis of 36 cohort-studies found a 17% reduced cancer mortality in the general population (i.e. people who did not have cancer at the time of the study). From those 36 studies, 5 look exclusively for colorectal cancer, 4 for pancreatic cancer, 3 for breast cancer and 22 for various cancers (8). Although there is not enough data to confirm this (1, 2, 8), other cancers (lung, pancreatic, prostate) seem to be prevented by physical activity.

Interestingly, someone who sits all day at work and exercises in the evening can be seen as sedentary. Sedentary refers to a state of muscle inactivity (like sitting or lying, with the exception of sleeping) regardless of engagement in physical activity (9). To our best knowledge there are currently no recommendations regarding the ideal daily sitting time. However, it is important to regularly break-up a sitting pattern. As studies have shown, sedentary behaviour increases risk of colon, endometrial and lung cancer (10, 11, 12).

Exercise … to help treating cancer

A recent meta-analysis of 35 studies (19 on breast cancer and 16 on colorectal cancer) concluded that the most active cancer survivors reduced their cancer mortality up to 22% regardless if they were previously active or not. Moreover, if they separated physical activity measured in the pre-diagnostic period from physical activity measured in the post-diagnostic one, the mortality reduction was greater in the post-diagnostic period (HR 0.60 vs HR 0.86). Thus, it seems that being active benefits to everyone (8).

Additionally, being active induces other somatic positive effects: preventing muscle wasting, decreasing osteoporosis risk, increase cardiovascular fitness, and seems to reduce some chemotherapy side effects (nausea and fatigue) (13).

Last but not least, exercise positively influences patients’ mood and social life by giving them greater independence based on Activities of Daily Living (ADL): improving their self-esteem, lowering anxiety and depression risk (13).

With their review, Browall et al. show physical activity as an adjuvant treatment for women affected by breast cancer. After the improvement of physical fitness, women feel content and empowered. They have the impression to have control over the disease. Given that they are not treated as patients, taking part in exercise programs also is a helpful tool for patients to gain a sense of normality, away from the medical sphere. Furthermore, it is also a chance for an opportunity to meet other people who suffer from the same disease and talk openly about it (13).

How does it work?

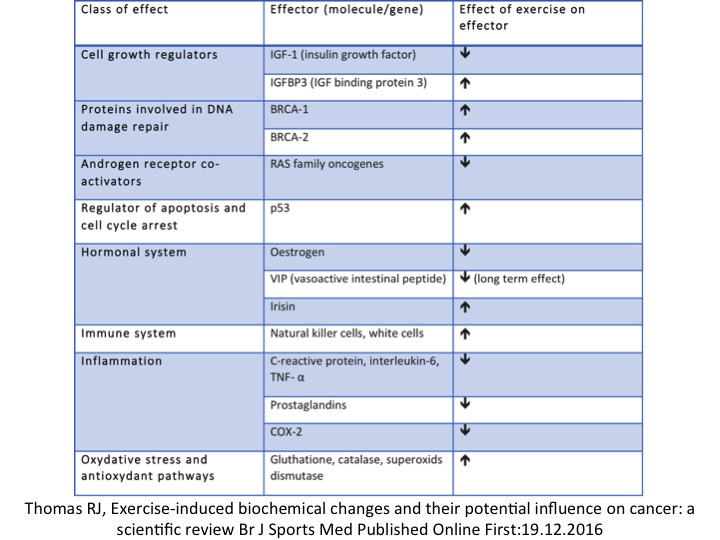

- Several mechanisms are described in the literature. They are listed in Table 1, which is reproduced from Thomas et. Al’s BJSM publication: Exercise-induced biochemical changes and their potential influence on cancer: a scientific review (14).

- Exercise has 4 mains effects:

- 1) Reducing hormones which promote cell growth and increasing mechanisms which protect the cell

- 2) Boosting the immune system

- 3) Reducing inflammation

- 4) Boosting antioxidants’ pathways

Others mechanisms include:

Increasing bowel movements

Exercise accelerates bowl transit and thus oncogenic substances pass through the bowel more quickly.

Preventing obesity

If obesity is a well-known cancer risk factor, exercise is much more than a weight control tool (1,2). To date, being obese and active is healthier than being normal weight and inactive; this is why fitness is more important than fatness (15).

Preventing metastasis

Regmi et al. studied the effect of physical activity on circulating tumour cells, which cause distal metastasis. By means of a microfluidic circulatory system, they simulated the high levels of shear stress that can be produced during exercise in the femoral artery. Hemodydamic shear stress can destroy circulating tumour cells in the blood stream. The researchers observed that the higher the stress, the larger the number of destroyed cells. Interestingly, this mechanism affects way more tumour cells (breast, lung, ovarian) than blood cells.They also observed the efficacy of shear stress on drug resistant breast cancer cells (16).

In the next blog we will speak about exercise oncology with an oncologist specialized in breast cancer.

******************

Giulia Marzano is a second year medical student at the University of Basel (Switzerland) with a great passion for sport. She is a member of Students & Junior Doctors SGSM/SSMS, she practices athletics and is specialized in middle-distance.

Email: giulia.marzano@bluewin.ch

Twitter: @MarzanoGiuli

Justin Carrard is a first year internal medicine resident based in Biel/Bienne (Switzerland). He coordinates the BJSM Swiss Junior Doctors and Undergraduate Perspective Blog Series and leads the Students & Junior Doctors SGSM/SSMS movement. Justin aims to raise SEM awareness among medical students and modern solutions it provides to big public health issues like non-communicable diseases. As an ex-competitive swimmer, he has a keen interest for endurance sports and regularly practices them with passion.

Email: justin.carrard@gmail.com

Twitter: @Carrard.Justin

If you would like to contribute to the “Swiss Junior Doctors and Undergraduate Perspective on Sport and Exercice Medicine” Blog Series please email justin.carrard@gmail.com for further information.

References

- IARC, Weight Control and Physical Activity. IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention, ed. H. Vainio and F. Bianchini. Vol. 6. 2002, Lyon: IARC.

- WCRF and AICR. Food, nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of cancer: A global perspective. 2007, Washington: American Institute for Cancer Research.

- Parkin, M., et al, The fraction of cancer attributable to lifestyle and environmental factors in the UK in 2010. BJC 2011. 105(Supp 2): S38-S41.

- Wu, Y., et al. Physical activity and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Breast Cancer Res, 2013. 137(3): p. 869-82.

- Wolin, K., et al. Physical activity and colon cancer prevention: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer, 2009. 100(4): p. 611-6.

- Robsahm, T.E., et al. Body mass index, physical activity, and colorectal cancer by anatomical subsites: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Eur J Cancer Prev, 2013.

- Moore, S.C, et al. Physical activity, sedentary behaviours, and the prevention of endometrial cancer. Br J Cancer 2010. 103 (7): 933-8.

- Li T, Wei S, Shi Y, et al. The dose–response effect of physical activity on cancer mortality: findings from 71 prospective cohort studies. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:339–345.

- Hamilton MT, Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Zderic TW, Owen N. Too Little Exercise and Too Much Sitting: Inactivity Physiology and the Need for New Recommendations on Sedentary Behavior. Current cardiovascular risk reports. 2008;2(4):292-298.

- Cong, Y. J. et al. Association of sedentary behaviour with colon and rectal cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. British Journal of Cancer, 2014. 110, p. 817–26.

- Schmid, D. & Leitzmann, M. F. Television viewing and time spent sedentary in relation to cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 2014. 106, p. 1–19.

- Shen, D. et al. Sedentary behavior and incident cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. PloS ONE 9, 2014.

- Browall M, Mijwel S, Rundqvist H, Wengström Y. Physical Activity During and After Adjuvant Treatment for Breast Cancer: An Integrative Review of Women’s Experiences. Integrative cancer therapies 2016; DOI: 10.1177/1534735416683807

- Thomas RJ, Kenfield SA, Jimenez A. Exercise-induced biochemical changes and their potential influence on cancer: a scientific review Br J Sports Med Published Online First:19.12.2016 doi:10.1136/ bjsports-2016-096343

- Barry, Vaughn W. et al. Fitness vs. Fatness on All-Cause Mortality: A Meta-Analysis Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases , Volume 56 , Issue 4 , 382 – 390

- Regmi S, Fu A, Qian Luo K. High Shear Stresses under Exercise Condition Destroy Circulating Tumor Cells in a Microfluidic System. Scientific Reports 2017; 7:39975