Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sport and Exercise Medicine blog series @PhysiosinSport

By Tom Goom @TomGoom, Sports Physiotherapist at the Physio Rooms and the creator of Running Physio; lead on Running Repairs Course http://www.running-physio.com/running-repairs-course/

Welcome to part 2 in this ACPSEM series about Achilles tendinopathy, starring #AchillesAl as a fictional case study. Part 1 covered training error and the development of symptoms. Thank you everyone who tweeted about the blog after. I’ve summarised your thoughts on Al’s training error using Storify below:

Here’s our twitter discussion from Part 1:

Part 1 concluded that too much high intensity training and a rapid introduction of treadmill running was likely to have overloaded Al’s Achilles and led to pain. The blog closed with a couple of questions from Al that we’re hoping to answer in this blog…

“What training should I do now then?”

“How could I modify it to help my Achilles?”

Once again we invite you to share your views about Al’s care using the hashtag #AchillesAl with @physiosinsport and @BJSM_BMJ.

Before we answer Al’s questions let’s explore some of the principles involved in the decision making process.

Risk vs reward

When we’re working with a patient to help them find the right level of training there isn’t just one right answer. It’s more about examining the options available and considering the risk (of injury or aggravating symptoms) versus the reward (optimising performance and achieving the patient’s goals).

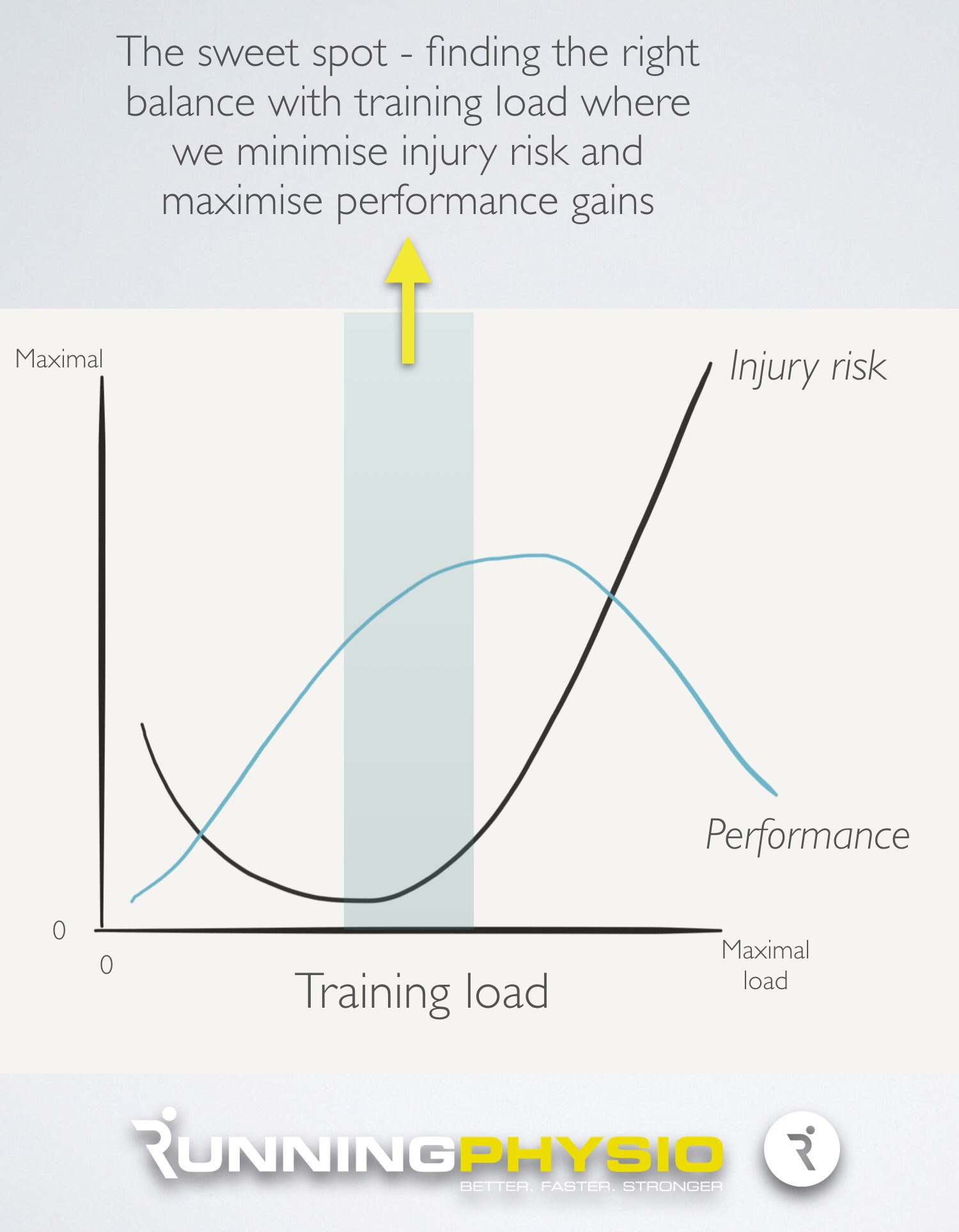

The aim is to strike a balance and reduce risk as much as possible while maintaining performance. Stopping running altogether may not be the lowest risk option. Al will lose fitness and tendons don’t respond favourably to being unloaded plus it’s common for people to develop an injury after returning from a rest from sport. It’s also likely that optimal training doesn’t just mean as much as possible! As training load increases above a point, there are diminishing returns and ‘overtraining’ is known to impair performance.

In reality then a graph of injury risk, performance and training load may look a little like this;

A key factor in risk versus reward and determining the right training level is the patient’s goal and the timescale involved. Al’s goal is a sub 3:30 marathon in 5 months time. This means we have time to achieve Al’s goal and improve his performance – we are not under pressure to take risks and can be a little more cautious with Al’s return to running. If, however, Al was competing in the Olympics in a couple of weeks time and he’d trained for 4 years to get there we might be more inclined to take risks for performance gains. Our approach might then centre around doing everything we can to reduce symptoms to allow Al to compete. Goal and timescale can make a big difference!

Determining load tolerance

Before we can advise Al we need to find out his load tolerance i.e. how much running he can currently manage (if any). Subjective questioning appears to be the best way to determine this as there are few objective tests that can reliably tell you how much running someone can manage. So we might ask Al, “how far can you run without pain?” It’s likely we’ll need to explore Al’s answers with him to get as much information as possible on what running conditions are most comfortable (distance, speed, surface, time of day etc) and how his Achilles responds to it both during and for around 48 hours after.

Our conversation with Al goes like this:

PT “How far can you run without pain?”

Al “It hurts a little almost immediately but then settles fairly quickly and I can keep going”

PT “It sounds like it warms up as you get going, that’s fairly typical of tendons. How far can you run until it starts to get sore again?”

Al “It’s pretty comfortable until around 8 miles then gets quite sore.”

PT “Where would you score that pain out of 10?”

Al “It’s around 3 or 4 at that point.”

PT “How does it react after the run and for the next couple of days”

Al “If I stop at 8 miles it settles quite quickly, and is usually fairly comfortable again within half an hour or so. If I keep going though it’ll ache after and be stiff the next day, especially in the morning. Then going up and down stairs first thing is uncomfortable.”

PT “Does speed make a difference? What pace have you been doing these runs at?”

Al “If I go faster it definitely hurts sooner, then it’ll stay sore for a couple of days. I’ve done most of these runs at around 8:30 to 9 mins per mile.”

PT “Ok, so would it be fair to say then that you can run about 8 miles at around 8:30 to 9 mins per mile and get some mild pain but it’ll settle quickly and be comfortable the next day?”

Al “Yes, that’s about it!”

With that conversation in mind, how might you modify Al’s training regime? What else might you want to know? What objective tests might you examine? How important are they in this decision? Share your ideas on #AchillesAl.

Training modification options

In tendon rehab we want to monitor how symptoms respond to load both during activity and after. Various studies have used a similar approach with this;

Pain should be minimal during activity (e.g. VAS 0 – 3 out of 10) and settle quickly with no reaction the following day.

Silbernagel et al. (2007) was a key paper in continuing sport with Achilles pain. They allowed athletes with Achilles tendinopathy to continue sport with symptoms up to 5 out of 10, providing there was no lasting reaction into the next day. Those that continued sport actually had better outcomes in some tests than those in the active rest group.

Our chat with Al has given us some really useful information. Running approximately 8 miles at a slow pace appears to fit within acceptable limits for pain – he has some mild discomfort during but it settles quickly and doesn’t lead to a reaction the following day. Our aim then for all Al’s training sessions is for them to sit within similar limits. Ideally we can find a way to make them pain free but we’re loading sensitive tissue so some pain is expected.

Options, options, options!…

One exciting thing with working with runners is you have lots of options of things you can modify to make running more comfortable and reduce load on injured tissue. Rather than rest altogether modify and move!…

Distance – as discussed above if we keep the running distance below the level that causes lasting irritation we can help reduce symptoms. In time we can gradually increase distance again to work towards Al’s goal.

Pace/ intensity – Al’s symptoms began largely due to high intensity training. Faster sessions aggravate his symptoms so at present we’ll stick with slower workouts but aim to reintroduce them when Al’s pain is less irritable and he’s developed more load tolerance.

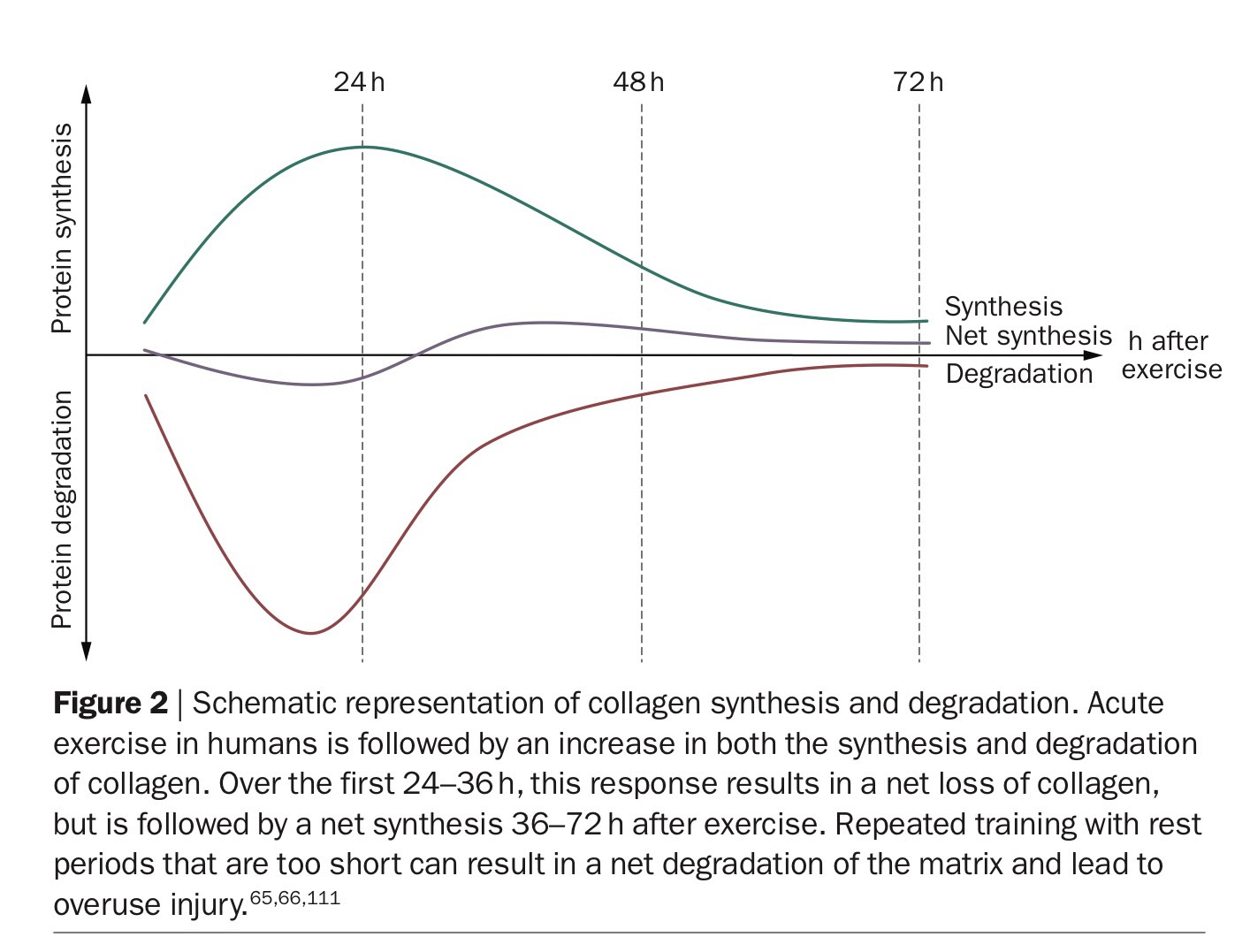

Frequency – reducing training frequency to allow a rest day between each run can be very helpful. Research suggests tendons may take 24-36 hours to recover from exercise. Magnusson’s work (as pointed out on Twitter by top Sports Therapist Ian Brown) indicates that it takes roughly this long for tendon synthesis to exceed tendon degradation;

Source: Magnusson et al. (2010) via Researchgate

Surface – the obvious example in Al’s case is treadmill compared to road running. As previously mentioned, Rich Willy’s recent work shows greater peak Achilles load on the treadmill so it would make sense to reduce Al’s treadmill running or remove it for the time being. This also reduces the risk of dying of boredom which can be a concern with prolonged treadmill running!

Time of day – early morning stiffness is a recognised feature of tendinopathy and some runners report their pain is worse with early morning runs. Switching to training later in the day may be more comfortable for Al, at least in the short term.

Cross-training – Al has a gym membership (it’s where he’s been doing his treadmill running) and has found his Achilles is pretty comfortable on the bike or swimming in the pool. We could replace some of Al’s runs with cross-training and try and achieve similar training goals. For example replace a long, slow run with a long slow swim, or swap an interval session on the track for an interval session on the bike. If we choose to restrict Al’s high intensity runs for the moment it would be good from a performance point of view to replace them with high intensity cross-training; a good way to achieve the balance of risk versus reward.

Recovery – optimising recovery is an important strategy, especially in high volume or high intensity training programmes. This can involve lifestyle change to improve sleep and stress (which we’ll touch on in more detail in later in this series). How and when we use rest/ active recovery is important. In Al’s case we could put a rest day prior to his longest run (so he isn’t fatigued when doing it) and one afterwards (to give him a chance to recover).

What else might you change? How might footwear influence symptoms? It’d be great to hear people’s views on this, especially from podiatrists! Get involved in the discussion on#AchillesAl.

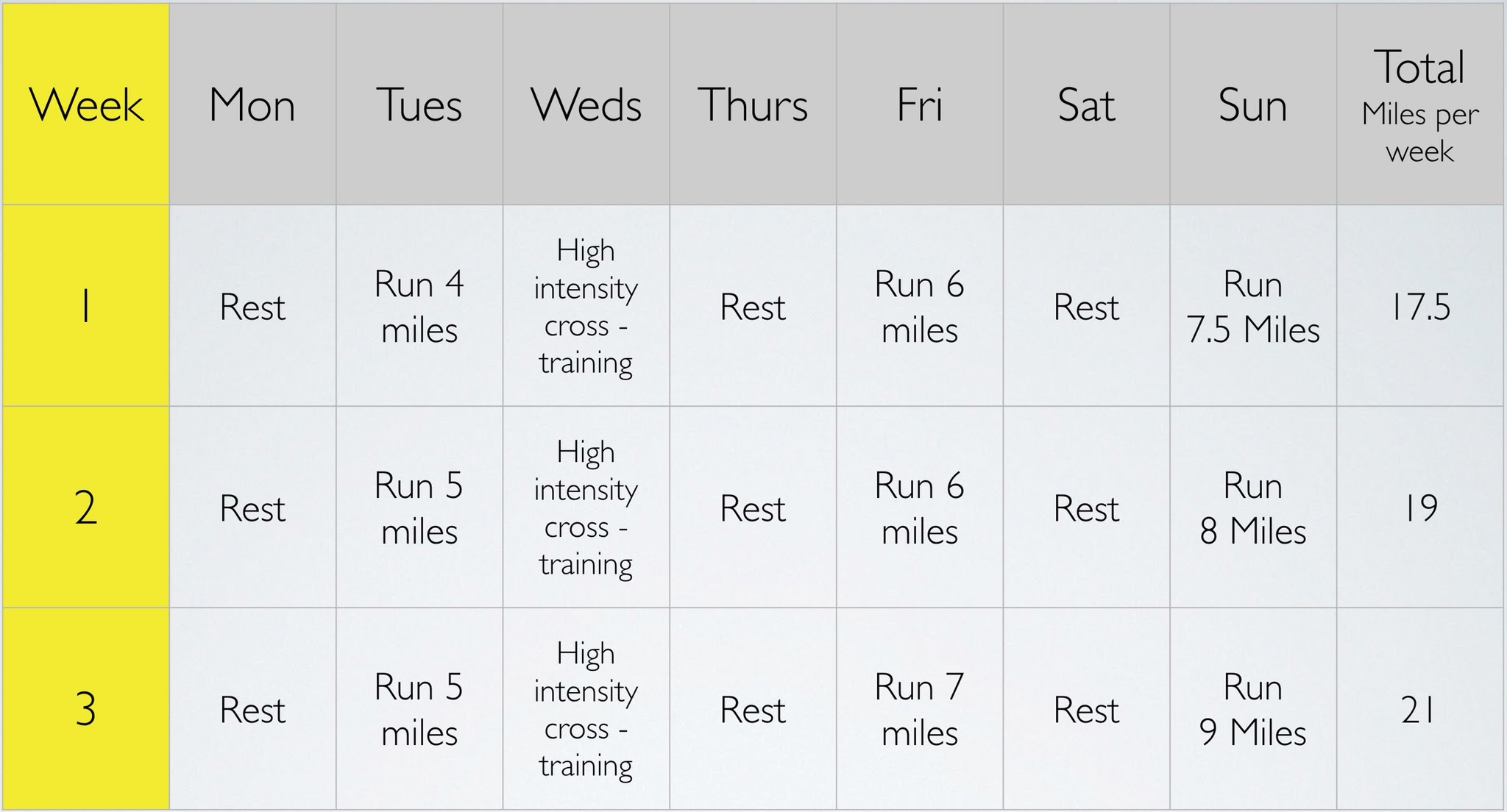

We have lots of options here and it’s important we aren’t too prescriptive. We can discuss the pros and cons of the options available with Al and decide a plan together. We’ll also be mindful that it will change as treatment progresses. Here is what we decided for the next 2-3 weeks;

In a nutshell we have 3 runs, each separated by a rest day and all of them at a slow pace and below 8 miles in distance (where symptoms worsened). The high-intensity run is replaced by a cross-training interval session on the bike, with a rest day after for recovery. We’ve removed treadmill running (which Al is pleased about as he never really enjoyed it!). This will take us to around 4 months until the marathon when we’re hoping Al can slip into a 16 week training programme, that starts at around 20 miles per week.

Thoughts from the MDT

Exercise Physiologist John Feeney from Pure Sports Performance joins us again to add his take on Al’s training…

“It’s important to identify the physiological mechanisms and effects of de-training and then try to mitigate those effects without aggravating the underlying injury. Initially, I would plan for a short term loss of training stimulus (<4 weeks) but also prepare a contingency plan in case Al’s injury becomes increasingly chronic and long-term (> 4 weeks). The strategy should focus on each key physiological area (maximal aerobic capacity, the sustainable percentage of VO2 max Al can utilise and running economy) and then introduce a training intervention to help mitigate the de-training effect on each of these areas. In the short term, we are likely to see a reduction in VO2 max due to decreased cardiac stroke volume and a rapid reduction in the level of chemical activity in the mitochondria which means Al may also become less efficient at utilising his fat stores thereby placing greater reliance on muscle glycogen. There will also be an increase in blood lactate levels which may result in Al becoming becoming less tolerant when exercising at increased intensities.

If the injury persists, longer term de-training effects become more specific to the trained skeletal muscle and so consideration should be given to introducing alternative sport specific exercises that involve the same muscle groups but without placing excessive stress and load on the injury. Exercises such as cross training using an elliptical trainer have been shown to maintain maximal aerobic capacity in the short-term (Joubert, Oden & Etes, 2011). Other sport specific exercises like deep water running are also likely to have a similar ‘maintenance’ effect provided the session frequency, relative intensity and duration are similar to Al’s pre-injury training plan. Non-sport specific exercises such as arm-cranking could be helpful in the short-term if Al needed to further reduce the load on his injury. An interesting study by Pogliaghi et al. (2006) found similar gains in VO2 max between an arm cranking group and a cycling group. Although this study was aimed at an older population, the results indicate that both forms of aerobic training (using different muscle masses – i.e. arms v legs), produced similar improvements in maximal and sub-maximal exercise capacity.”

Planning for the future

We’ve agreed a plan with Al for the next few weeks but it isn’t set in stone. We’ll need to see how he responds to training and adapt it accordingly. We’ll also need to gradually re-introduce the high intensity running and return to his goal weekly training volume of approximately 40 miles per week. There’s no recipe for this but it’s usually sensible to change one thing at a time (e.g. Volume or intensity) and monitor symptom response.

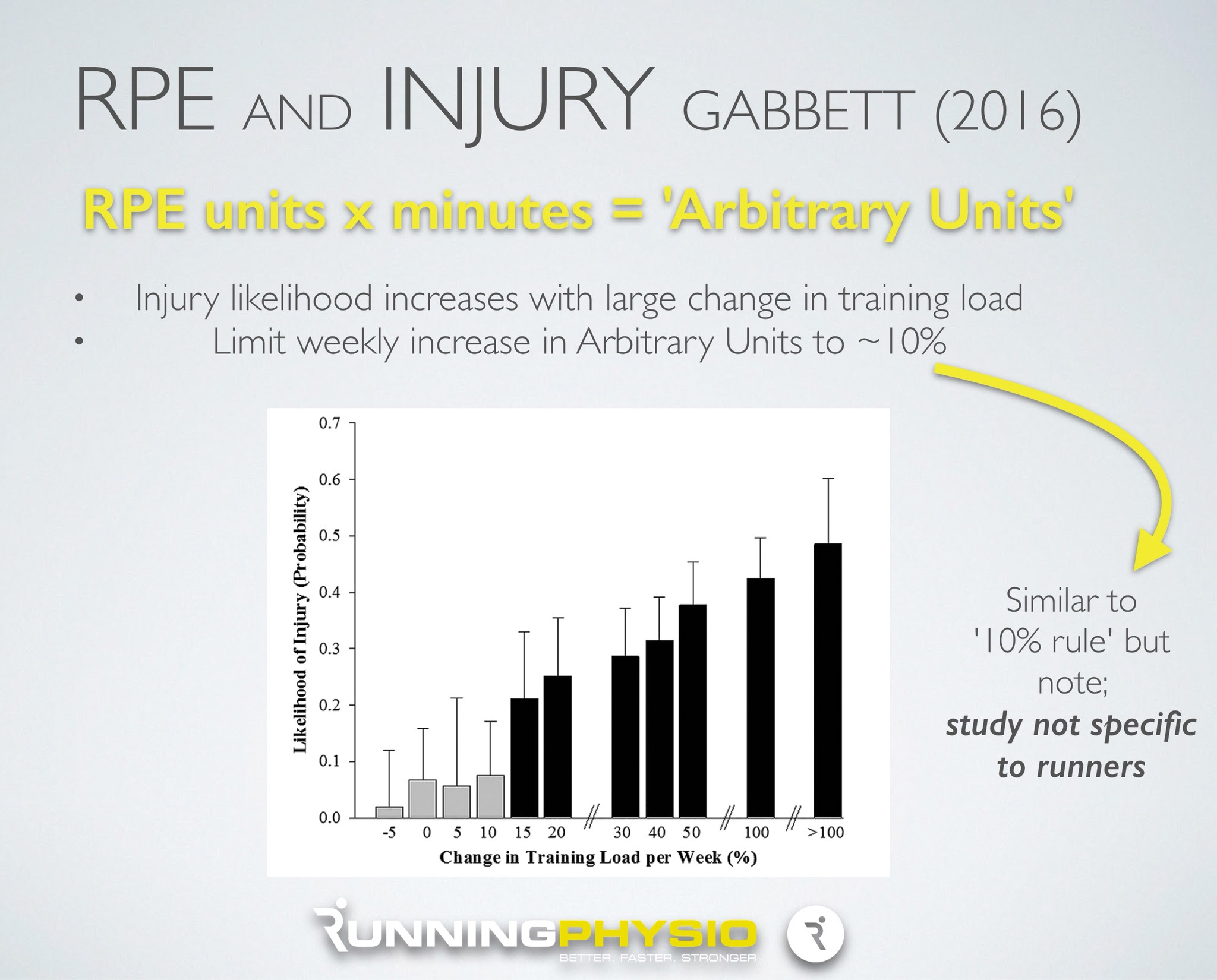

Going forward, one strategy we could use that could both improve performance and reduce injury risk is to ask Al to record the RPE (Rate of Perceived Exertion) for each session. Dantas et al. (2015) found RPE correlated well with blood lactate levels in desired training zones in runners and so can be a useful way to determine the right training intensity. Effort is rated out of 10 where 0 is no effort and 10 is maximal. Roughly 2 to 4 on this scale corresponds to low intensity training (e.g. Long slow run). Approximately 4 to 7 would be moderate intensity (e.g. Tempo runs) and above 7 would be high intensity (e.g. Interval training).

Tim Gabbett’s excellent recent work combines RPE with training volume to give a measure of overall training load, referred to as Arbitrary Units (AU). For each session you multiply training volume (in minutes) by the athlete’s RPE score to provide the total AU e.g. 50 minute run at RPE of 4 = 200 AU.

If we think back to part 1, one of the issues we had was that training volume itself didn’t change a great deal so training error might not have been obvious. If we’d had RPE for each session we might have been able to spot a trend more clearly.

In runners we often use the fabled ‘10% rule‘ suggesting weekly training volume (e.g. Miles per week) shouldn’t increase by more than 10% per week. There isn’t a great deal of evidence to support this in runners but Tim Gabbett’s work did find an increase in injury risk (in rugby league) when Arbitrary Units increased by more than 10% per week;

We could ask Al to get into the habbit of recording RPE during training and calculating total weekly training load in Arbitrary Units. Monitoring this and adapting as necessary could help Al improve his performance and reduce injury risk. Win, win!

Al is happy with the training plan but a little apprehensive about returning to training. He has a few questions about how the tendon will cope;

“Will continuing to run damage my tendon?”

“Is it likely to lead to a rupture?”

What do you think? How would you address these concerns? We’d love to hear your views, share them on #AchillesAl and we’ll include the highlights, plus our answers to these questions, in part 3…