By Sam Blanchard (@SJBPhysio_sport)

Age is just a number, right? Or is that just something adults say to convince ourselves our body clock is ticking differently to the kitchen clock and the seemingly more frequent turns of the calendar?

When working with young athletes I think these two clocks are undoubtedly out of synch. Line up three 13 year olds and try and guess their age. You would think one was just about to sit their 11+ at school, one could buy you a lottery ticket and the other – well they probably look about 13.

Despite individual differences in the rate & timing of maturation, we categorise athletes by their chronological age, often to fall in line with their school year. But at what cost? Barnett & Dobson (2010) recorded 33% more than average AFL players being born in the first month of the season and 25% less than average in the last month of the season. Similar trends are also seen in the English Premier League. Although that may not sound too alarming, as high as 75% of young athletes will drop out of sport around the age of 13. I want to consider the reasons and implications for this along with the question “what can the medical team do about that?!”

Children grow at their fastest rate in the first two years of infancy. However, we’re unlikely to see them in sport at this age! It is not until the adolescent growth spurt that we start to see issues relating to co-ordination and performance (Hewett et al 2004, Quatman-Yates et al 2012). As well as increased incidence of apophyseal injuries like Osgood-Schlatters, we also see an increased risk of joint injuries, which I discuss in an upcoming BJSM podcast, related to control of long-levers.

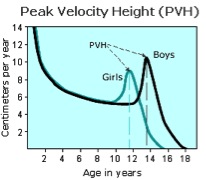

In girls we see this growth spurt around the age of 11-12 & in boys usually around 13-14 and it’s within this time that we see growth rates escalate up to 10-12cm per year. As with everything though, there are outliers. Without our crystal ball, it’s tricky to tell who will hit their spurt at what time. Using the Mirwald calculation (2002), we can get an estimate of the onset of this Peak Height Velocity (PHV) as well as a predicted height at the end of maturation (+/- 5cm). In males we have a tell-tale sign suggesting they have surpassed their PHV, indicated by facial hair. A quick, non-invasive assessment indicating that their growth may now settle to a few centimetres a year, which is much more manageable. In females, the development of breast tissue and the onset of menarche would also be secondary signs of maturation. Although a little more invasive due to questioning, menarche is a key stage of development that triggers hormonal changes of which the medical team should be aware.

What implications does this have?

Let us go back to those stats, with most professional sportspeople being born closer to the start of the season. Growing up, you are more likely to have a head start on the rest of your peers in school. Especially in the years preceding PHV, so around ages 6-12. The danger here is that the older children will be better at games than the younger children – this is do with development of motor learning, co-ordination, potentially size. So already we start to filter out chronologically younger children due to confidence & waning participation. With growth spurts starting around 13 years old, perhaps the 75% of drop-outs are from those born later in the calendar year? How much potential are we missing out on in these early years? I am being careful not to discuss one sport in particular, because different sports in different countries will have different cut-offs for age groups – regardless of “when” in the calendar, there will always be an oldest & youngest (chronologically) either side of this cut off.

By the time children reach Peak Height Velocity, the chances of them “specialising” in a sport will have increased. Chances are they are within an academy of sorts relating to their specific sport. Here we start to see a conflict between physical & technical development. Early developers that can physically outplay their peers won’t be challenged in a way that develops their technical side – why learn how to outwit an opponent when you can just hold them at arm’s length? Equally late developers may not be able to get near the play for similar reasons. The argument with the late developers however, is you start to see them problem solve in other ways – “how can I create space for myself?” or “I need to be a step ahead of the play in order to avoid a crunching tackle.”

If we move outside of team sports and look at individual events like athletics, how can we maintain the motivation for late developers to keep competing against physically more advanced peers?

What can we do?

Children aren’t’t born into academies, they are developed in grassroots. Perhaps along with coach education, we need to be discussing maturation and physical development with those involved in recruiting. In football there are extensive networks of scouts assessing grassroots talent. A little bit of knowledge of physical maturation combined with their sporting knowledge could open their eyes to previously ignored players.

The IFSPT definition of a sports physiotherapist includes “enhancing sports performance” (Competency 4: IFSPT competencies here) – so it’s incorrect for physiotherapists or strength & conditioning coaches to think they don’t have a role in talent ID or nurturing. We need to be part of the discussion about managing young players and encouraging development, not just of those early developers that may burst onto the scene at 16, 17 years old – but equally those late developers that may be a hidden talent, whispering in the background.

Detailed knowledge of growth & maturation, along with patience and attention to detail, can help us individualise training for players. When to work on balance & co-ordination or when to start loading in the gym. When to challenge players outside of their comfort zone or when to retreat way back into it. This involves playing the long game – and may be something that traditionalists feel uneasy about. But if we can create an environment where its fluid for players to move between age groups without the stigma of “playing up” or “playing down” then perhaps we can help improve the statistics of teenagers remaining in sport – perhaps even the odd one or two making it professional.

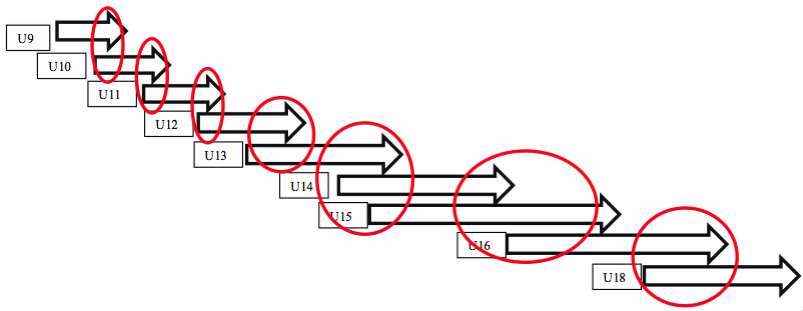

The diagram above is perhaps how we should be considering our grouping of players. Rather than a straight continuum progressing linearly from one age group to another, understand that players’ development will overlap across divisions. A smaller under-15 can physically present the same as an early developer in the u13s, suggested by the red circles overlapping multiple age groups during the adolescent growth spurt. If we can encourage coaches, players and parents to be comfortable with this then perhaps we can start talking about players competing “across” age groups, rather than “up or down”. It is also important to understanding that player development is a continual process, requiring regular assessment & re-assessment.

Conclusion

The exciting part about working in sport is that our role extends beyond injury management & prevention. We are an important cog of large machine that helps develop & maintain sporting talent. In youth athletes in particular, we have a big responsibility to nurture and develop talent and ensure that the technical demands of training are balanced with physical attributes. Even though the odds of a young athlete making it professional are slim, if we can keep them interested enough that they continue playing at some level as an adult, this will very likely have a positive impact on their life.

*******************************************

Sam Blanchard (@SJBPhysio_sport) is a senior lecturer in physiotherapy at the University of Brighton. He is also the South East representative for the ACPSEM (Physios in Sport) and Lead organiser of the 2015 biennial conference in Brighton, 9-10th October: “The Young Athlete” – early bird tickets available until 31st May 2015 please visit physiosinsport.org for more information. He has recorded a BJSMpodcast on this topic that is in production right now.