Guest blog by Phil Coles (@PhilColesPhysio)

Making the decision of when an athlete should return to play after an injury is one of the most challenging parts of a sports clinician’s role. This is especially so when working with professional sporting teams, where the pressures can be immense. Ideally, a clear decision making process should be combined with reliable clinical objective markers to reduce the potential for the ‘personality bias’ of the clinician leading to error in these decisions.

Being aware of personality bias

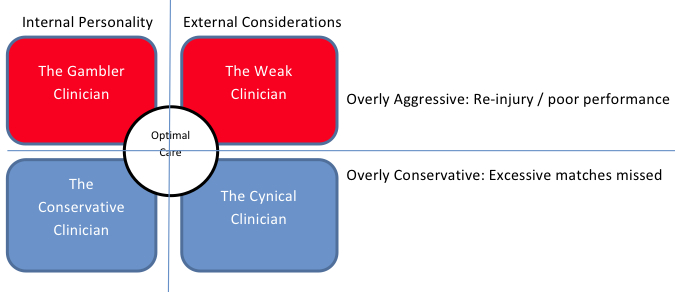

Rehabilitators working with elite athletes may have their own ‘personality bias’ that can expose them to the risk of two opposing yet equally significant errors.

On the one hand, the clinician may tend to be overly aggressive. This could be an internal compulsion (the ‘Gambler’ clinician) or may be the result of external pressures leading them to rush a player back in to competition before it is reasonably safe for them to do so (the ‘Weak’ clinician). Premature return to competition can lead to athletes breaking down with re-injury or simply performing below expectations. If however, an injury does recur in the early stages of a return to competition, then it (perhaps reasonably) exposes that clinician to direct blame for a poor outcome. Any poor performance related to physical deficits may also negatively affect the clinician’s relationship with the player and or their coach / manager. Both of these outcomes may in fact put that clinician’s career at a club in jeopardy, and this is a fact of which most clinicians are well aware.

On the other hand, the clinician may tend towards to being overly conservative. This may also be due to internal compulsion (the ‘Conservative’ clinician) or because of fear of the consequences described above (the ‘Cynical’ clinician). If athletes are kept out for longer than necessary to reduce the risk they might break down or perform below expectations on their return, it will mean they miss valuable competition time. This second type of error is not as immediately obvious to the coach / athlete and therefore it is less likely to bring direct blame to the clinician. Naturally if there is a pattern of consistently delayed recovery over a long period of time then it may reflect poorly on those involved. However, it is much more difficult to blame them directly, as it is never really clear as to when any individual athlete could have returned from a particular injury.

Perhaps contrary to expectations then, it is likely many clinicians default to the position of being overly conservative. Unfortunately this means some will make a conscious choice to be overly conservative, not in the best interests of the player or the team, but rather in the hope of reducing any risk of being held liable for the more ‘obvious’ poor result (re-injury or poor performance).

What is the cost of ‘delayed’ return to play?

To highlight the true cost of unnecessary conservatism from the cynical clinician to a club, consider the following example. If a football team that plays once a week was to have 30 injuries over the course of a season and all those injuries were given just one extra week of rehabilitation more than was really necessary, that would cost the club a total of an extra 30 missed games. Consider then if all those players actually came back 1 week earlier as perhaps many of them could, but this caused 5 players (17% of injuries) to re-injure the same area. In the case of each of those 5 re-injuries, if the athlete missed a further 4 weeks, the club would lose players for an extra 20 games. This means that despite those recurrences, the club would have cut their total number of games lost to injury by 30% (from 30 to 20 games lost). Dr John Orchard (@DrJohnOrchard) made this point in his review of injuries and re-injuries in AFL in 2005. From his analysis at the time he concluded ‘at this stage it may be a sensible strategy to allow earlier return to play in team sports and accept a low-moderate re-injury rate’ after having seen such a pattern in the reported data.

In reality, of course, there any many modifying factors that would need to be considered in each individual case. For example, is there extra risk of recurrence with an earlier return for that particular injury, and how long recovery likely will take after re-injury? Also, other factors such as the point of the season, the particular game, and the position being played etc. will influence whether or not a risk is worth contemplating for an individual athlete at a particular time.

What happens in real life?

The reality is that clinicians working with high level athletes must recognise that it may be equally as negative to have a bias towards conservatism as it is to have bias towards aggression in rehabilitation. Although most clinicians working in an elite environment would probably deny that they ever knowingly act overly conservatively, in reality most would (if being honest) admit there have been times when they have taken longer to return a player to competition than was perhaps essential because they feared the repercussions of any re-injury. Conversely, most would also accept that there have probably been times when they allowed issues that don’t directly relate to the injury into the thought process that ultimately allowed a player to return prematurely. Sports clinicians must be brave in the sense that they must be able to withstand the outside forces which might encourage a rushed return to play, but they must be equally brave in backing their own ability and judgement in getting a player back when the relative risk is reasonable, rather than waiting for the risk to be nil, which of course it will never actually be.

The judgement of what is a reasonable risk is where the real skill of a sports rehabilitator lies. The ability to make this judgment correctly in a more consistent fashion, relies firstly utilising a clearly defined decision making process. The actual process of that return to play decision making was well outlined by Matheson et al (2011). They described a thorough model for considering all the factors that may affect our clinical judgement when deciding on the return to play of an athlete. The first two steps are to evaluate the athlete and the risk of returning to sport. This involves assessing the health status of the athlete and then considering that against risks particular to that sport and in that athlete. This is where improved objective markers would be particularly useful. Having decided that someone may return based on these principles, they acknowledge that there are still many ‘modifiers’ to your final decision which must be considered, and so ultimately clinical reasoning remains paramount. These modifiers would include consideration of issues such as the timing and season, the stage of an athlete’s career, the importance of athlete to the team, the importance of a particular game to the athlete, any conflicts of interest at play (such as financial reward to the player or therapist), any chance of masking occurring, and risks of litigation etc.

What objective measures are there?

The ability to make return to play decisions objectively will help to decrease the potential of clinician personality bias to lead to error. For this reason I contend that developing improved objective markers that may predict a safe return to play is perhaps the greatest research need for rehabilitators working in high level sport.

Unfortunately there are not yet many proven objective markers for sport specific return to play, but there are certainly some clinical tests that may be considered to reliably assess for known risk factors to injuries. Consider these examples.

(1)The Hamstring active flexibility and apprehension test developed by Asking et al (2010) is a reliable test which is more sensitive to picking up on-going Hamstring deficit than traditional assessment methods. (Click here to listen to a podcast with Carl Askling about hamstring management). Considering that hamstring recurrences are such a problem in the football codes it would be reasonable to suggest a normalisation on that test along with all other traditional clinical signs is essential before endorsing a return to play.

(2) A decrease in adduction power as measured by a squeeze test may predict the onset of groin pain in AFL players (Crow 2010). Perhaps therefore after any groin injury a reasonable objective milestone that must be met during rehabilitation before being allowed to progress to full loading is that an athlete must have reached at least their pre-morbidity levels on that squeeze test. (Per Holmich’s podcast on groin pain is here; his short YouTube video is here).

In summary, to clear an athlete to return to play there needs to be confidence that the rehabilitation has been complete, and that a clear decision making process was followed. You must be aware of the dangers of ‘personality bias’ among clinicians and we should attempt to minimise this through the use of objective clinical testing wherever possible. Perfect judgement is impossible but clinicians and managers should appreciate that being overly conservative can be an equally significant and perhaps more common error as being overly aggressive. They should also accept that using objective markers is the way to minimise this. If the current markers fail us or do not exist in the sport specific detail we would like, it does not mean we should shy away from using objective markers, it means we should dedicate time to developing more accurate ones.

References

Orchard et al. Return to Play following muscle strains. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15:436–441.

Matheson et al. Return to play decisions- are they the team physician’s responsibility? Clin J Sport Med 2011;21:25–30.

Crow et al. Hip adductor muscle strength is reduced preceding and during the onset of groin pain in elite junior Australian football players. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 13 2010; 202–204.

Askling et al . A new hamstring test to complement the common clinical examination before return to sport after injury. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:1798–803.

Stay tuned for the BJSM podcast on this topic with Liverpool FC’s Darren Burgess

***************************************************************************

For the past 2.5 years Phil Coles has been head of Physical Therapies at Liverpool Football club. Prior to this he was head physiotherapist for the Socceroos including the 2010 World Cup, and an associate lecturer at the University of Sydney. You can follow Phil on twitter @PhilColesPhysio.