Figures often beguile me, especially when I have the arranging of them myself; in which case….’There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies and statistics’. – Mark Twain

A beguiling and artful video promoting exercise went viral: a good thing, right? Delighted tweets and emails came at me from people whose judgment I respect. They keep coming. But each time I see more praise and still no criticism, my heart sinks.

Is this reception happening because literacy about risk of bias in research is far too low? Or don’t enough people oppose the use of framing techniques that magnify effects rather than putting them in realistic proportions? Or is it because people condone biased data being used to exaggerate effects if it’s for a cause they believe in? Or do people only see bias very selectively? All are a cause for concern.

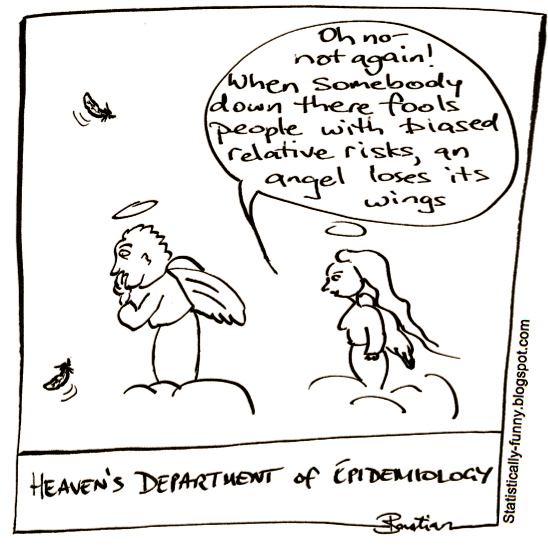

People’s alarms should always go off when faced with a slew of relative risks without any absolute measures to place it in context. It is the classic “go to” framing technique for exaggeration, be it researchers, journalists, manufacturers or anyone else wanting to make benefits or harms sound as big as possible. On its own, a relative risk is actually uninformative: from what to what? is what we need to know. Reducing or increasing a tiny effect remains a tiny change, even if it is by a huge relative margin. In this video, claims based only on relative risks were made for 11 specific conditions, plus death and quality of life.

To support the data, the narrator mentions 1 meta-analysis, 1 definite trial, some cohort studies (at least one of which he refers to as a trial) and a survey. The one meta-analysis was for anxiety. I don’t know which one he means – there were no references – but for the two I identified (1st link here, 2nd here) in the last few years, the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination indicated reservations about the reliability of evidence in both.

Good quality trials at a low risk of bias are short in this area, but once they are done, they often reveal that effects are only modest. That’s not surprising, given what a confounder exercise is. Are very active people less depressed and ill because they exercise – or are people who are on top of the world just more likely to be getting out and about more too?

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not saying there are no proven benefits of exercise. Of course there are. But for most health outcomes, rigorous systematic reviews have conclusions like: “no strong evidence to support or refute” or “some modest short-term benefits but no evidence for long-term health effects”. (More systematic reviews here)

Figures can be beguiling, as Twain says. But when data are biased and then framed in biased ways that magnify effects, they deny people wisdom and the opportunity to make well-informed choices among options presented on a level playing field. Buttressing claims with biased (and thus likely-to-be-refuted) data might also contribute to a lack of trust in science and statistics.

The issue of bias is a matter of serious import and principle. We need to be rigorous about all health claims – even (and perhaps most especially) for those we want to believe most earnestly to be true.

***********************************************************

Hilda Bastian‘s involvement in health began with consumer advocacy in Australia. She has been working in the fields of communicating about and assessing effectiveness since the late 1980s.