Film Review by Professor Robert Abrams, Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

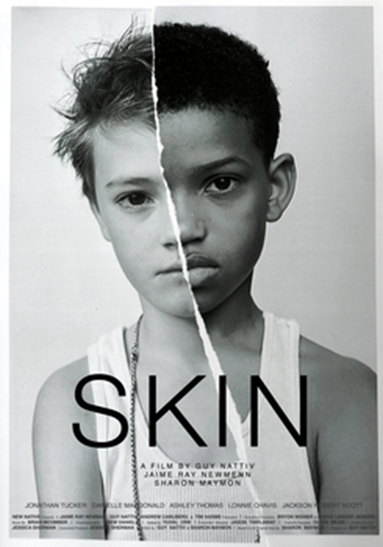

Review of Skin (2018), directed by Guy Nattiv, USA.

“You have to be taught …to hate and fear…before you are six or seven or eight …you have to be carefully taught” Lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II for the musical ‘South Pacific’ (1958).[1] These wise, memorable lines, sentiments that somehow survived the scrutiny of American film censors, were bold and almost revolutionary for the 1950s, a time when Jim Crow laws[2] still humiliated, restricted and segregated the lives of “colored” citizens throughout the U.S. South. That is the atmosphere if not necessarily the exact period depicted in the film, Skin, the winner of an Academy Award for Best Live Action Short Film.

Skin was first released in 2018, recently enough, yet in what feels now like a different era. But this film’s moving and layered analysis of racism is especially timely this year, in the aftermath of the extrajudicial killings of African-American men by police officers in Minneapolis and Atlanta, and in the midst of a COVID-19 pandemic that has laid bare the extent of economic and healthcare disparities based on race. Both situations are now understood to be steeped in pervasive institutional racism and have inspired demands for reform in the U.S and throughout the world.

Skin tells the story of Troy, a boy aged about ten, living somewhere in the rural South with his father and mother, both of whom are presented initially as loving parents. The film is loosely constructed on the premise of the Hammerstein lyric but extends it considerably; where Hammerstein focuses on the vulnerable child, Skin also examines its complex principal “teacher” of hatred, who in this case is the boy’s father, a backwoods ‘good ol’ boy” who relishes guns, beer and the raucous company of his heavily tattooed white buddies, all looking like members of a white supremacist group.

The film suggests how the transmission of racist attitudes from parent to child might be paradoxically enhanced by the fact that this boy’s father cannot be entirely dismissed as an archetypal Southern “redneck.” In the early scenes, for example, he appears to be capable of affection, for his wife, although he is rather domineering toward her, and especially for his son, in whom he tries to impart his love of guns and daredevil games. In fact, Troy’s father says nothing that explicitly demonizes blacks, so his racism is conveyed in action, not words. Troy himself is at this stage innocent of racial animus.

One evening, the family—father, mother and son—are shopping at the local supermarket. A kindly black man from across the checkout aisle responds to Troy’s interest in the toy he is carrying for his own young son, who happens to be about Troy’s age. Meanwhile, Troy, who appears to have a peaceful, friendly nature and has not yet been taught enough, or seen enough, to hate, stands aside, while his father proceeds to confront the stranger threateningly. The man replies that Troy had only been interested in his toy, and then, exasperated, becomes testy himself. At that point the father reaches for his phone to call on his posse of other “good ol’ boys” to punish a black man who had shown the temerity to object to a false accusation by a white man. In a horrific scene, they beat him savagely, nearly to death, against a window of his car, while his wife and son, Bronny look on helplessly. Troy then becomes a reluctant witness to the act of brutal racism and cowardice orchestrated by his father.

There are other toxic aspects of this teacher of hate that warrant a closer look. Reinforced by his friends, Troy’s father assumes a persona so exaggeratedly hypermasculine that a viewer would have to consider his swagger to be a form of psychological defense. The defense is presumably directed against a self-perception of male inadequacy that must be emphatically refuted by the way he behaves outwardly. His racism, too, is a part of that defense, in that his hatred and fear of the “other” is used by him to counter any doubts about his own manliness and sexuality.

As a principle at the very center of the film, it is implied that the hater or teacher of racist hate not only inflicts pain upon others, but in the end traumatizes himself, albeit in ways that cannot be foreseen. The viewer of Skin experiences this notion as an eerie premonition starting from the film’s opening scenes. That feeling grows ever more discomfiting as the story unfolds, until it reveals itself in the form of a vengeful Dante-esque finale. By any measure, the three lives in Troy’s family have been destroyed, in different ways for everyone, but beyond remedy for all.

To watch the trailer and / or buy a copy of the film, follow this link, https://vimeo.com/ondemand/skin2

References

[1] ‘South Pacific’ film (Joshua Logan, 1958, USA), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Pacific_(1958_film).

[2] Jim Crow laws, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jim_Crow_laws#:~:text=Jim%20Crow%20laws%20and%20Jim,U.S.%20military%20was%20already%20segregated.