Fortnightly we invite a colleague to share a clinical tip with our community. Today, Jane Thornton, a BJSM Editor, is on the stage.

Who are you?

I am a Sport Medicine Physician and Canada Research Chair in Injury Prevention and Physical Activity for Health, and an Assistant Professor (Department of Family Medicine, Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics and School of Kinesiology) at Western University in London, Ontario, Canada. I am also an Editor of the British Journal of Sports Medicine. My research focuses on long-term athlete health, female athlete health, and physical activity in the prevention and treatment of chronic disease.

What clinical tips would you like to share with the community?

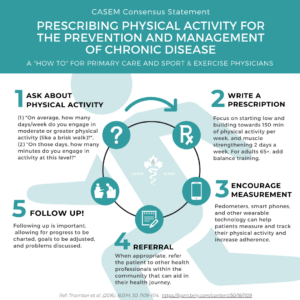

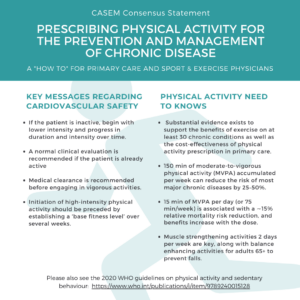

I’m going to outline how I prescribe physical activity. As we all know, physical activity can reverse or help manage the symptoms of many chronic conditions and help prevent and treat musculoskeletal conditions. It’s under-prescribed for a variety of reasons. Physicians cite lack of time, training and trust as barriers to including physical activity in their counselling practices. Patients face barriers to being active that are social, demographic and cultural. A lot of my research is spent trying to understand more about patient and physician barriers and to find solutions that work. Here’s how I translate this research into my own practice:

- Pre-screen your patients if you can. Most of us already do this in some form or another (e.g., medical history forms completed in the waiting room). But pre-screening can also take the form of asking about behavioural change, goals, etc. We have shown that screening patients in advance is a help for both patient and provider as it can save physicians time while also helping patients achieve their prescribed physical activity level. We ask patients about co-morbidities (focusing on contraindications to physical activity prescriptions such as uncontrolled/poorly controlled chronic conditions or acute cardiac concerns), but I also ask about current physical activity levels, goals and readiness for change.

- WRITE A PRESCRIPTION. Tailor your advice to individual needs and preferences, and goals. Use technology to your advantage when you can. Our pre-screening forms are filled out online or on a tablet in the waiting room. The answers are run through an algorithm and a personalized physical activity prescription is generated in their electronic medical record. We determine amount, type of intensity of physical activity based on the WHO Guidelines but start with increments that align with the patient’s current abilities and goals. Our physicians can refine their prescriptions based on their follow up conversations and add notes and resources.

- ENCOURAGE MEASUREMENT and have patient handouts and resources on hand to help. Patient handouts are low-cost educational tools that are effective in improving patient care and outcomes. We created the “My Active Ingredient” peer-to-peer healthcare hub, currently active on Twitter through the @myactivingrednthandle (our website is launching soon!). The hub signposts physicians and patients to the best available free physical activity resources and it’s co-designed with patients and people with lived experience. Measurement can also be an individual thing, we use free apps, some use accelerometers, others use daily logs. Find what works for you.

- REFER IF APPROPRIATE By referring patients to allied health professionals (physiotherapists, occupational therapists, exercise professionals, registered dietitians), physicians may benefit from sharing assessments and personalized consultations. This can be very helpful particularly for patients with cardiovascular disease and/or Type 2 diabetes, as well as special populations that have difficulty engaging in physical activity due to low motivation or safety concerns (patients with cancer, epilepsy or pulmonary disease). Often, referral can be present an additional burden of treatment such as added costs for the patient or difficulty accessing care, important to consider as those most at risk of disease are often the least able to afford the cure.

- FOLLOW UP. Follow up is key to increasing patients’ motivation and adherence. Patients expect their physicians to address physical activity regularly. I generally follow up every 2-6 months depending on the patient.

The whole process usually takes 5-15 minutes. The initial clinic visit (by the time I see them, the forms are all filled out, the prescription is auto-populated on my electronic medical record) takes about 10-15 minutes, follow up is usually shorter. This excludes any physical examination I may need to perform, or addressing any contraindications (e.g., uncontrolled Type 2 diabetes).

Where does it come from?

Patients! Everything we do is informed by and co-designed with people with lived experience and our community members. I have also learned from my colleagues around the world on best practices. Leading the Canadian Academy of Sport and Exercise Medicine’s 2016 Position Statement on physical activity prescription made me aware of how fortunate we are in sport and exercise medicine to have strong international consensus on the topic, as several sport and exercise medicine societies endorsed the statement. We also benefitted from the work of medical student Lawson Seddon, who helped design an accompanying infographic (which conveniently provides a nice summary of the above advice!).

What is its scientific evidence, if any?

Please find here some references to find more information on this topic:

- Thornton J, Fremont P, Khan K, Poirier P, Wells G, Fowles J, Frankovich R. Physical activity prescription: a critical opportunity to address a modifiable risk factor for the prevention and management of chronic disease: a position statement by the Canadian Academy of Sport and Exercise Medicine. Br J Sports Med 2016 Sep;50(18):1109-14.

- Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2020;54:1451-1462.

- Reddeman L, Bourgeois N, Nicholas E, et al. How should family physicians provide physical activity advice?: Qualitative study to inform the design of an e-health intervention. Canadian Family Physician 2019;65.

- Agarwal P, Kithulegoda N, Bouck Z, Bosiak B, Altman L, Birnbaum I, Reddeman L, Mawson R, Propp R, Thornton JS, Ivers N. Feasibility of an eHealth tool to promote physical activity in primary care: A cluster randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res 2020;22(2):e15424) doi: 10.2196/15424