Fortnightly we invite a colleague to share a clinical tip with our community. Today, Justin Carrard, a BOSEM Associate Editor, is on the stage.

Who are you?

I am a Swiss resident physician sharing my time between a postdoc position at the University of Basel and my postgraduate clinical training in general internal medicine & sport and exercise medicine (as SEM is not a medical specialty in Switzerland, it is necessary to specialize in another field too). My clinical interest lies in managing fatigue in athletes of all levels. It is fascinating to see how far the human limits can be pushed while trying to remain in a healthy zone. On my research days, I am applying high-throughput metabolomics and lipidomics approaches to comprehensively phenotype physiological reactions to exercises, which is linked to my clinical interest.

What clinical tips would you like to share with the community?

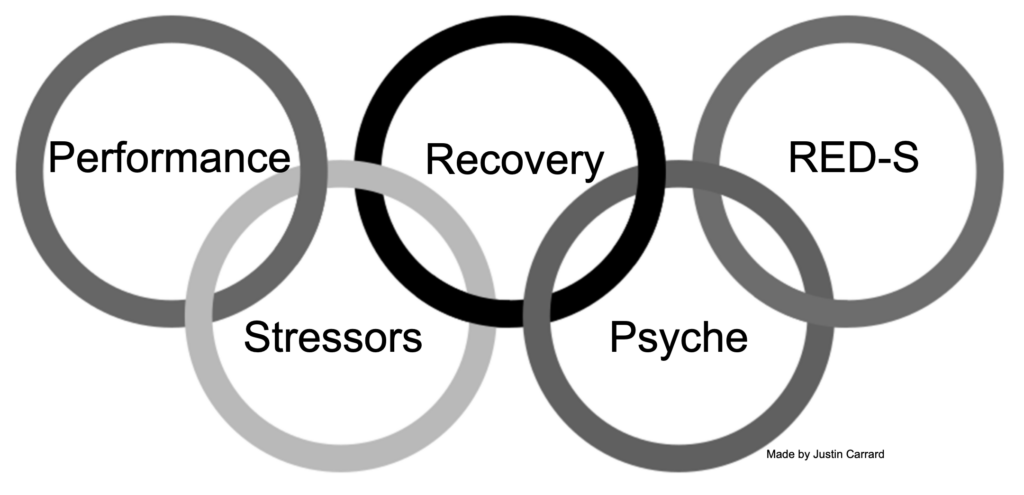

When it comes down to fatigue in athletes, it is essential to plan enough time in your schedule for these patients. I usually book a full hour for a first appointment. During this time, I conduct extensive history taking, addressing all possible causes of fatigue. Remember that athletes are human beings (not only a mix of joints). To help me conduct a comprehensive anamnesis, I developed a diagram based on the Olympic rings in which each ring represents a sphere of the patient’s life I want to address (Figure 1).

Shortly, I ask about:

- performance (mainly changes in performances),

- stressors (sport-related like change in training load, competitions, but also unrelated to sport such as relationship difficulties, troubles at school/work, financial problems, etc.),

- recovery (are recovery methods in place? recovery day? nutrition? sleep quality and quantity, etc.),

- psyche (symptoms of depression or other psychiatric diseases, sadness, work/sport-life balance, etc.),

- RED-S syndrome symptoms (eating disorders, menses, past injury and illness, growth, etc.).

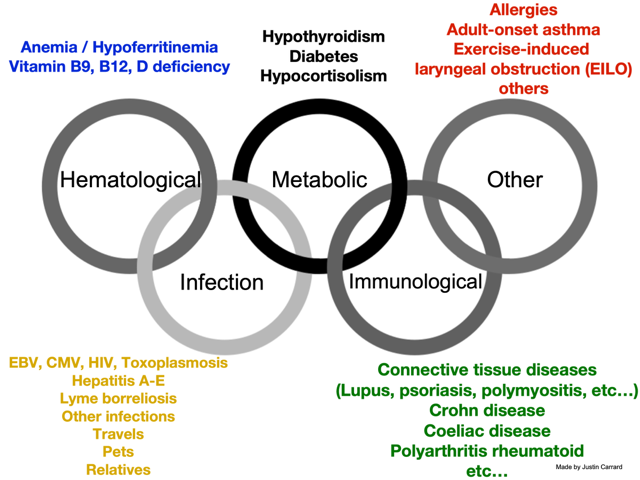

During this time, you should begin reviewing potential differential diagnoses in your mind. Here, I use the five Olympic rings again to guide me in this task (Figure 2).

Briefly, I consider disorders related to the following domains:

- haematological (including vitamin deficiency)

- infection (here it is essential to ask about travels, animal contacts (for a toxoplasmosis or toxocariasis infection, for instance)),

- metabolic (ask for symptoms of hypo- or hyperthyroidism, etc.)

- immunological (think of coeliac disease as the chameleon of gastroenterology, it can do almost all symptoms; remember that lupus can mimic a lot of disorders too),

- other (do not be obsessed with your idea, avoid the tunnel vision, and keep your mind open).

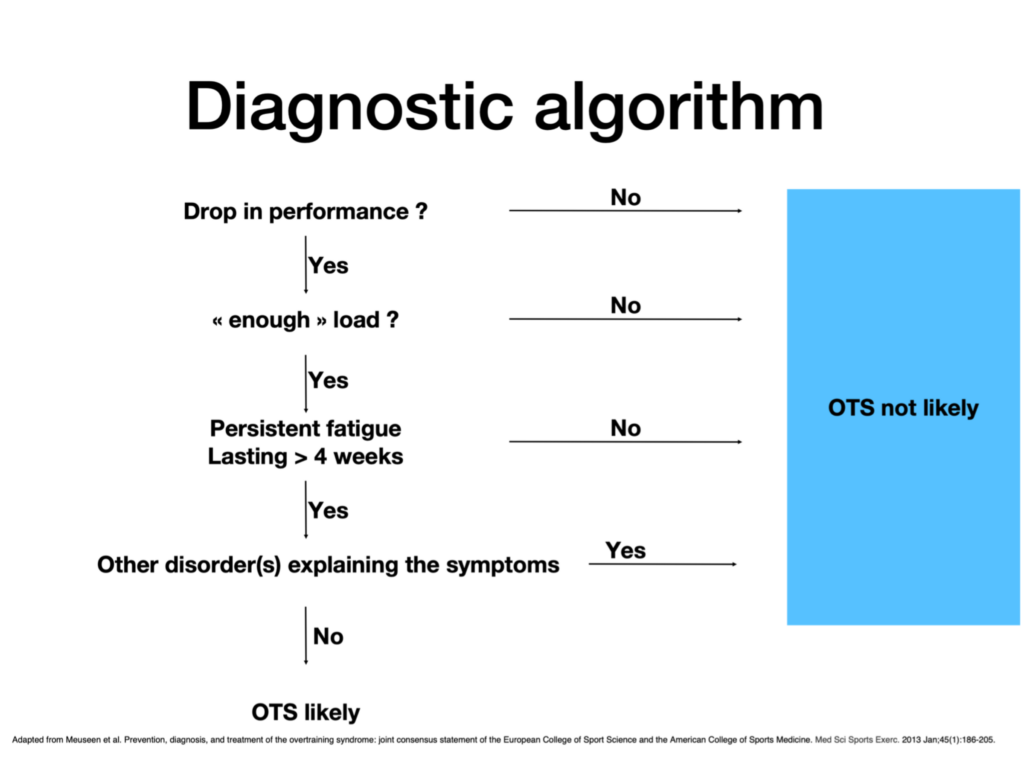

It is then necessary to conduct a thorough physical examination and order blood examination to rule out most potential differential diagnostics (however, it is impossible to rule out every diagnosis). Figure 3 displays the algorithm I use in clinical practice (OTS stands for overtraining syndrome).

Where does it come from?

I usually try to follow the advice Prof. Karim Khan once tweeted (I think it was him): “be the dumbest person in the room”. This is a great way to improve (or at least try to) constantly.

I learnt a lot from my mentor Dr Boris Gojanovic, who also has a keen interest in complex medical/internal problems in SEM. In addition, I read a lot of articles on fatigue, overreaching, overtraining syndrome, RED-S syndrome, and published a few myself (1, 2).

What is its scientific evidence, if any?

The level of scientific evidence is generally relatively low in the field of fatigue and overreaching/overtraining syndrome (as evidenced by our recent scoping review (1)).

However, there are a few excellent papers I can recommend (3-11).

References

- Carrard J RA-C, Hinrichs T, Appenzeller-Herzog C, Schmidt-Trucksäss A. . Diagnosing overtraining syndrome: a scoping review protocol. . 2020.

- Carrard J, Kloucek P, Gojanovic B. Modelling Training Adaptation in Swimming Using Artificial Neural Network Geometric Optimisation. Sports (Basel). 2020;8(1).

- Pearce PZ. A practical approach to the overtraining syndrome. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2002;1(3):179-83.

- Meeusen R, Duclos M, Foster C, Fry A, Gleeson M, Nieman D, et al. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of the overtraining syndrome: joint consensus statement of the European College of Sport Science and the American College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45(1):186-205.

- Meeusen R, Duclos M, Gleeson M, Rietjens G, Steinacker J, Urhausen A. The Overtraining Syndrome – facts & fiction. European Journal of Sport Science. 2006;6(4):263-.

- Soligard T, Schwellnus M, Alonso JM, Bahr R, Clarsen B, Dijkstra HP, et al. How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(17):1030-41.

- Schwellnus M, Soligard T, Alonso JM, Bahr R, Clarsen B, Dijkstra HP, et al. How much is too much? (Part 2) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of illness. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(17):1043-52.

- Halson SL, Jeukendrup AE. Does overtraining exist? An analysis of overreaching and overtraining research. Sports Med. 2004;34(14):967-81.

- Stellingwerff T, Heikura IA, Meeusen R, Bermon S, Seiler S, Mountjoy ML, et al. Overtraining Syndrome (OTS) and Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S): Shared Pathways, Symptoms and Complexities. Sports Med. 2021;51(11):2251-80.

- Robson-Ansley PJ, Gleeson M, Ansley L. Fatigue management in the preparation of Olympic athletes. J Sports Sci. 2009;27(13):1409-20.

- Halson SL. Monitoring training load to understand fatigue in athletes. Sports Med. 2014;44 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S139-47.