Last week I pointed out that some errors in citations from the Oxford Textbook of Medicine (OTM) had been corrected in the latest set of additions to the OED. This has prompted me to look more closely at the quotations from the OTM that appear in OED citations.

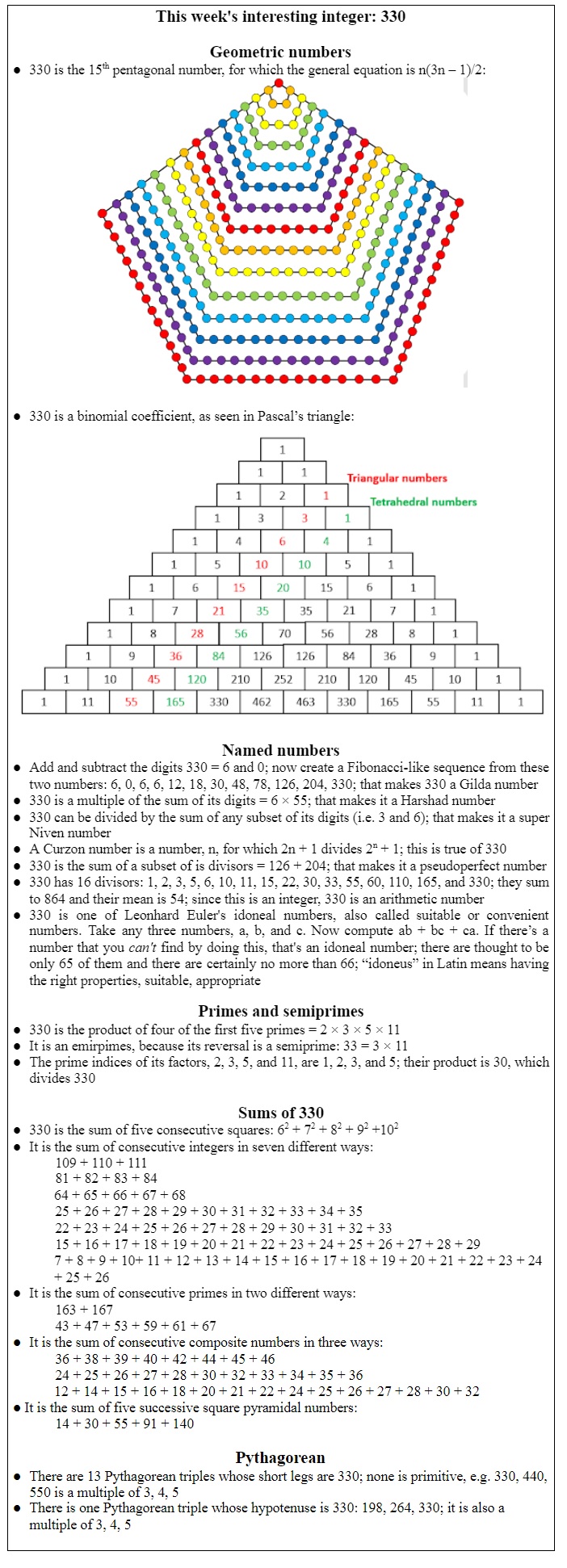

The OED contains 246 quotations from different editions of the OTM under 228 different headwords: 74 from the first edition (1983), 157 from the second (1987), and 15 from later editions. Each citation consists of a quotation and the source from which it comes. The distribution of the numbers of quotations under the 228 headwords is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The distribution of numbers of citations under each of 228 headwords in the OED having at least one citation from the OTM (18 have two)

Why does the dictionary contain so many citations from the OTM? For comparison, all other books with the word “textbook” plus “medical” or “medicine” in their titles contribute only 35, the nearest rival being Derrick Dunlop, with or without my erstwhile teacher, Stanley Alstead, both Scottish professors of therapeutics; their Textbook of Medical Treatment (1939, 1961, and 1966) notches up 13 citations in all.

The OTM and OED share the same publisher. But the Oxford lexicographers have clear-cut criteria for choosing specific quotations to include, which transcend parochial interests. For example, the Oxford Handbook of Clinical Medicine and the Oxford Handbook of Medical Sciences have contributed only one citation each, while Passmore & Robson’s Companion to Medical Studies has 302. It and the OTM have been quoted so often because they are such rich sources of material.

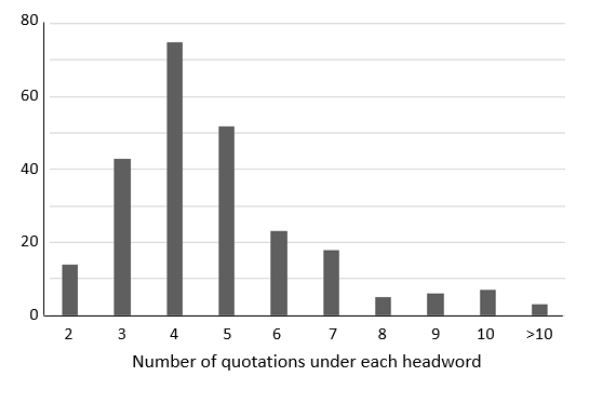

The first citation under each headword is the earliest instance that the lexicographers have found. In the OTM collection there is only one such case. Marburg disease and the Marburg virus were first described in 1967 by Siegert et al. from the Hygiene-Institut der Universität Marburg/Lahn, in a paper published in the Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift. They noted that some laboratory technicians and animal-house workers at the Behringwerke in Marburg and the Paul-Ehrlich Institute in Frankfurt, who had been in contact with monkeys or their blood or tissues, developed a haemorrhagic fever, which they traced to a virus that had not previously been described. The English term “Marburg virus” first appeared in The Lancet in June 1968 and “Marburg disease” in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report in December of that year. However, just as one might talk of “Ebola” rather than “Ebola fever”, one can talk about “Marburg” rather than “Marburg disease”. Here is the quoted example from the 1983 edition of the OTM, in a chapter by ETW Bowen and DIH Simpson: “On 15 January 1980 Marburg reappeared, this time in Kenya”. But here is the title of a paper that appeared in The Lancet on 12 March 1977: “After Marburg, Ebola”; this antedates the OED’s earliest cited instance by 6 years and gives The Lancet a double whammy of firsts. This is just one of 40 antedatings I have found of the earliest citations given under the 228 headwords to which the OTM has contributed examples (Figure 2); about half of them come from The BMJ.

Figure 2. The distribution of the numbers of years by which 40 of the 228 headwords can be antedated

Earliest quotations earn entry by being the earliest identified. However, later quotations need more than that. The first editors of the OED (the New English Dictionary as they called it) intended each headword to have at least one citation from each century, although that was not always possible; sometimes only one citation could be found, which had to do; when no recent citation could be found for a word that was still in current use the editors would make up an example. “Plaster” is a good example; the dictionary includes two citations from Old English, one or two from each century from the 14th to the 19th, and four from the 20th, including one from the OTM.

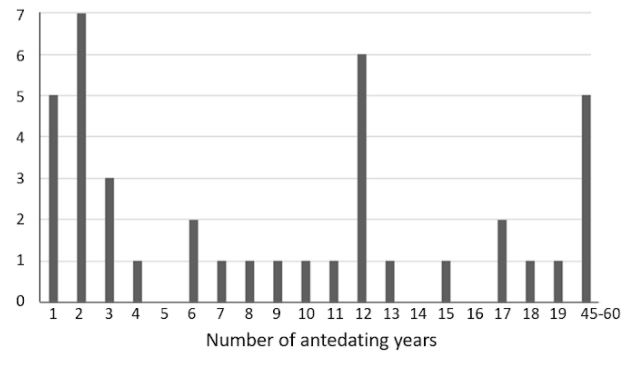

Sometimes a quotation is included in order to show that a word is not obsolete or rare; 30 of the OTM examples may have been chosen for that reason, when the lag between the penultimate and the last entry is long enough, say more than 25 years (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The distribution of lag times between the penultimate quotation and the last quotation under a headword, when the last quotation is from the OTM; when the lag is an arbitrary 26 years or more, as it is in 30 cases, the quotation shows that the word is still in current use

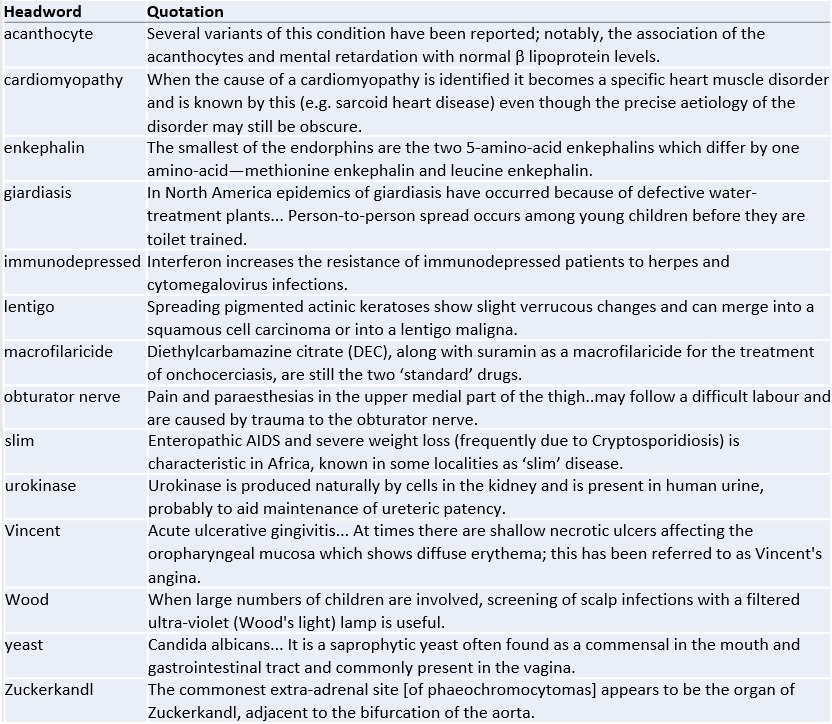

But the best reason for including a quotation is that it demonstrates some facet of the meaning of the word, particularly one that has not been demonstrated by previous quotations. Some good examples from the OTM are listed in Table 1. Many of the OTM entries in the OED fulfil this criterion.

The OED has chosen a rich collection of medical quotations from a thorough textbook.

Table 1. An A to Z of OTM definitions from the OED

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: none declared.