The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) is updated every three months (“on a quarterly basis” as they put it—they mean “quarterly”). The latest list of updates and additions, published in March 2021, contains 744 items. There are four categories:

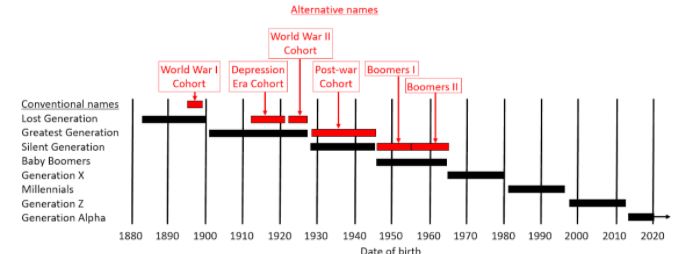

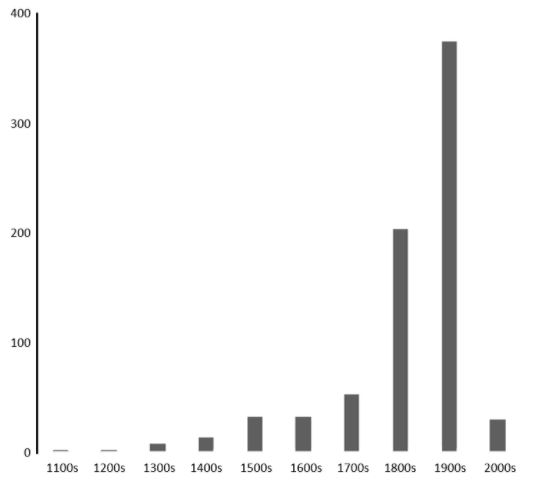

- Words that are completely new to the dictionary This list (151 entries, of which 41 have two new definitions each) starts with “à la Chinoise” and ends with “zoomer”. A zoomer is either a member of Generation Z (Figure 1) or, as a more recent usage has it, a baby-boomer who has reached middle-age or retirement age. More succinctly, a baby boomer who hasn’t grown up. As a baby boomer, I recognize the phenomenon. Perhaps “Zoomer”, one who communicates using Zoom, will make it into the dictionary next time. The verb to Zoom is already there. I’m a frequent Zoomer, so there’s an example to cite. Other meanings include a Nintendo flight simulator joystick, a robotic toy dog, and a Canadian radio station.

- New sub-entries Compound words or phrases that are now included under other headwords (235 entries). The list starts with “aceboy”, included under “ace”, a colloquial term for a close male friend, said to have originated as an African–American usage, but now mainly used in Bermuda. It ends with “zither-like”.

- New senses of old words This list (322 entries) starts with “abstain”, meaning “to stay away from one’s workplace, school, etc”, a South Asian usage. It ends with “zizzy”, “characterized by or involving a buzzing or whizzing sound”.

- Additions to unrevised entries New senses, compound words, or phrases that were already included as draft entries appended to the end of existing entries, now fully incorporated (36 entries). These are also included in the other categories.

Figure 1. Conventional and alternative names for the generations of Western populations; taken from various sources, including the US Census Bureau

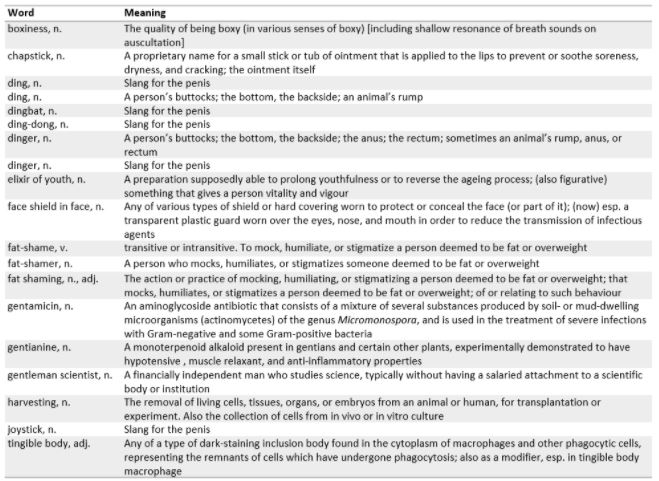

Items that are new to the dictionary do not have to have been recently coined—the dictionary is constantly catching up. Figure 2 shows a frequency distribution of the numbers of entries whose first citations date from each century since 1100; some are surprisingly old.

Figure 2. Frequency distribution of the dates of the first citations of the new entries in the OED, March 2021 (excludes one entry cited from early Old English)

The newly entered words of medical, or quasi-medical, interest are listed in Table 1. The list includes two pharmacological compounds.

Table 1. New medical or quasi-medical entries in the OED included in the March 2021 list

Gentamicin was first described in 1963, so it is surprising that it has taken so long for it to appear in the dictionary. Although the name was originally spelt “gentamycin”, the spelling was changed early on to “gentamicin” on the recommendation of the American Medical Association’s generic names committee, because, unlike many other antibiotics whose names end in –mycin, it was isolated from a genus of Micromonospora, not from Streptomyces organisms. Even so, a PubMed search shows that the spelling with –mycin occurs in about 10% of publications. Indeed, if you did not search databases for incorrect as well as correct spellings of gentamicin, you would miss several publications, including systematic reviews, that use the incorrect spelling.

The other compound, gentianine, seems to have made little impact, although it was mentioned in Chemical Abstracts as long ago as 1946. A PubMed search yielded only 23 hits, mostly in vitro and animal studies. It’s said to have hypotensive, muscle relaxant, and anti-inflammatory properties.

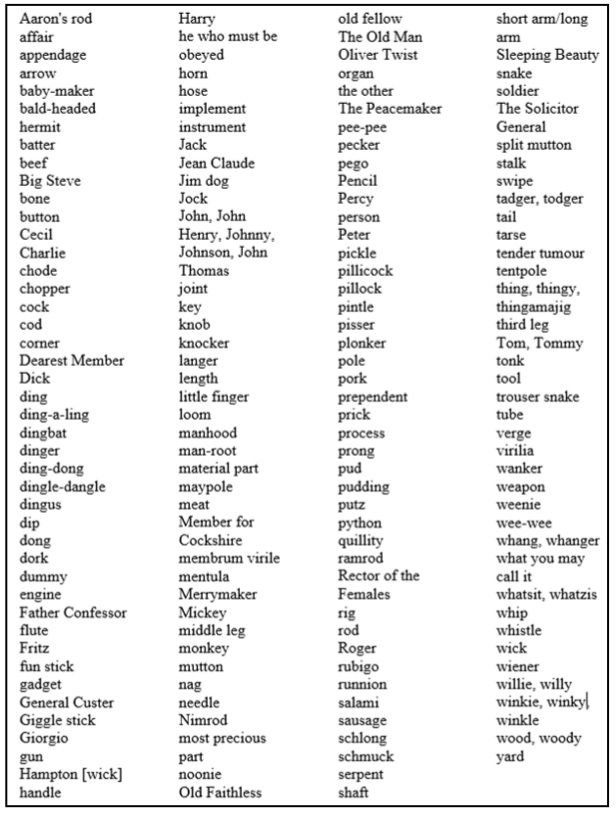

One set of entries that stands out, as it were, from the list are the five slang terms for the penis. This is by no means an exhaustive list, although one might get exhausted just thinking about it (Table 2).

Table 2. Slang and euphemistic terms for the penis. Apart from the OED, my sources include:

Ayto J. Euphemisms. London: Bloomsbury, 1993.

Holder, RW. The Faber Dictionary of Euphemisms. London: Faber & Faber, 1969.

Holder, RW. TA Dictionary of Euphemisms. Oxford: OUP, 1995.

Neaman J, Silver C. In Other Words. A Thesaurus of Euphemisms. UK: Angus & Robertson, 1991.

But the term I like best is “gentleman scientist”, defined as “a financially independent man who studies science, typically without having a salaried attachment to a scientific body or institution”. The dictionary cites an example from 1895 and also an article from a 1975 issue of the New Scientist magazine: “The days of the gentleman scientist are over; we’re professionals, we’re paid well …”. Consequently, the dictionary labels this “now chiefly historical”, but if that is so it should, in my view, be revived. It might be nice to be thought of as a gentleman scientist, were it not for the fact, judging from the activities of many twitterati, that the juxtaposition is a contradiction in terms.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.

|

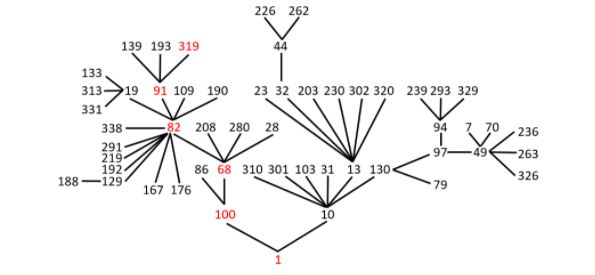

This week’s interesting integer: 319 Geometric numbers

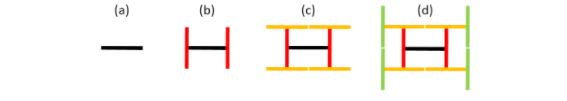

(a) Lay down a toothpick (black)

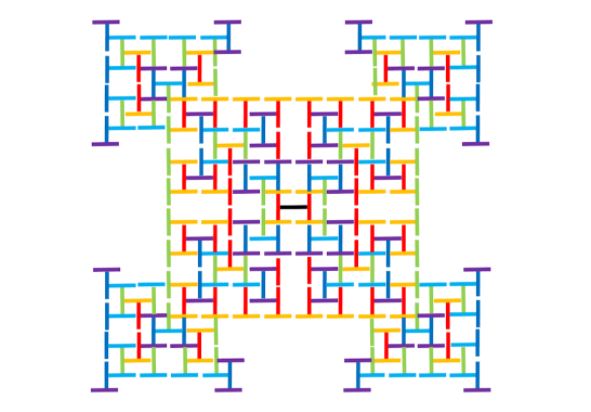

(e) Keep repeating; after 25 cycles you will reach the pattern below, which contains 319 toothpicks

Named numbers

Semiprimes

Sums of 319

159 + 160

159 + 160

The first three squares: 1, 4, and 9

Pythagorean

319, 360, 481 Of these, the first and fourth are primitive Miscellaneous

|