Three words reflecting two types of Chinese therapies can be found among the biomedical words first cited from 1979 in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) (Table 1)—tui na, a form of massage, and qinghaosu and artemisinin, used in malaria.

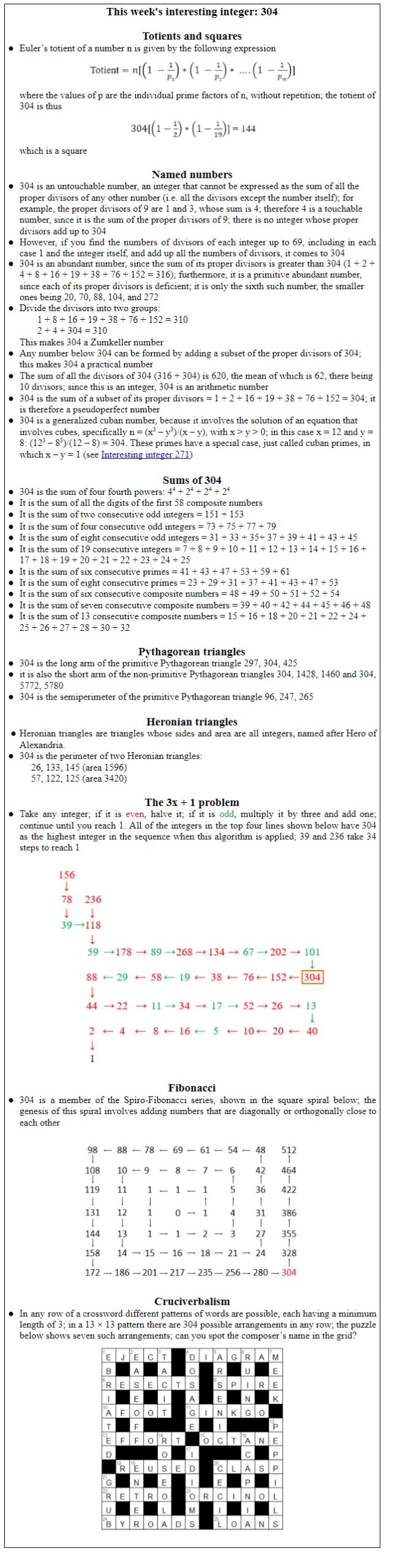

Table 1. Biomedical words (n=38) in the OED for which the earliest citations are from 1978 (out of a total of 228); I have found five antedatings, from 2 to 84 years

*Antedatings: ecotoxicity (1978), transposase (1978), lentivirus (1977), parvoviral (1977), tui na [t‘ui na] (1895)

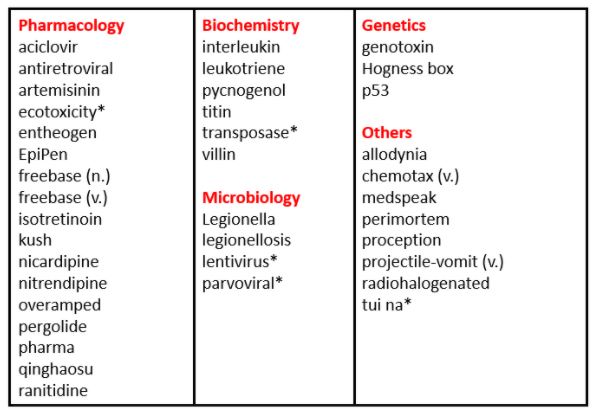

Tui na, from two Chinese words meaning to pull and grasp, is a type of therapeutic massage, a sort of mixture of acupressure and qigong. The 1979 citation in the OED, from the Chicago Tribune, informs us that “Tui-Na is very hard to learn and very hard to teach”. But the technique is an ancient one, and it is not surprising that it was mentioned, along with other forms of Chinese massage, in the British Medical Journal in 1895 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A description of tui na [t‘ui na] in the British Medical Journal for 26 October 1895

In modern times, tui na has been trialled in a wide range of conditions. The results of some of these are summarized in Table 2. Investigators have generally reported no adverse effects, but in one patient with ankylosing spondylitis tui na resulted in bilateral fracture dislocation and fatal tetraplegia, so it is probably best avoided when there is pre-existing spinal damage.

Table 2. The results of trials of tui na in various conditions, reported in publications listed in PubMed

| Condition | Type of study | Result | References |

| Parkinson’s disease | Open pilot study combining tui na, acupuncture, and qigong (n=25) | Worse motor scores; improved quality of life and less depression | 2006 |

| Fibromyalgia | Relaxing yoga plus touch with tui na (n=16) versus relaxing yoga (n=17) | Some short term benefit | 2007 |

| Dysmenorrhoea | Acupuncture (n=30) versus acupuncture plus tui na (n=30) for 3 months with follow-up for 3 cycles | Improvement in 73% versus 93% | 2008 |

| Childhood anorexia | Meta-analysis of three RCTs (n=332) | “Larger randomized, controlled trials are required” | 2014 |

| Knee osteoarthritis | Observational study n=30 | Less pain; greater flexor power in the right knee and extensor power in the right knee; range of movement unchanged | 2016 |

| Post-stroke spasticity | Prospective multicenter blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial (n=90) | Less spasticity in four muscle groups (Modified Ashworth Scale); no effect on Fugl-Meyer Assessment | 2017 |

| Low back pain | Randomized, unblended, controlled trial feasibility study of acupuncture and tui na alone and together (n=101) | Some improvement in self-rated pain, but mostly non-significant changes (depending on the statistical tests used) | 2017 |

| Cervical radiculopathy | Meta-analysis of five studies (n=448) | Reduced pain; low quality evidence | 2017 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome | Single-blind, randomized trial (n=20) | Small improvements (P=0.049, paired t-test) | 2017 |

| Chronic fatigue syndrome | Randomized, single-blind, comparison with acupuncture (n=77) | Small improvements | 2017 |

| Acute diarrhoea in children | Meta-analysis of 26 studies (n=2644) | Small improvement compared with pharmacotherapy; low quality evidence | 2018 |

| Acute diarrhoea in children | Meta-analysis of 26 studies (n=2410) | Small improvement compared with pharmacotherapy; low quality evidence | 2018 |

| Upper limb spasticity after stroke | Multicenter, single-blind, randomized comparison with conventional treatment (n=444) | Improvement in three muscle groups in those treated within three months, but not later | 2019 |

| Insomnia | Meta-analysis of 22 RCTs (n=1999) | “more high quality RCTs and well-designed protocols … are needed” | 2019 |

| Parkinson’s disease | Systematic review of 12 studies | “Longitudinal studies are needed to justify the introduction of massage therapy into clinical practice.” | 2020 |

| Mammary gland hyperplasia | Retrospective comparison with Chinese medicines (n=68) | Improvement in 94% versus 77%; recurrence rates 13% and 23% | 2020 |

Qinghaosu and artemisinin, which are therapeutically more impressive, featured in the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, which was awarded for two novel therapies for infections. William C Campbell and Satoshi Ōmura were honoured “for their discoveries concerning a novel therapy against infections caused by roundworm parasites”. The novel therapy was avermectin. The drug we now call ivermectin is a mixture of avermectin H2B1a and avermectin H2B1b. Ivermectin is effective in the treatment of a range of parasitic conditions such as onchocerciasis, strongyloidiasis, and lymphatic filariasis. It has also been touted as a treatment for covid-19, but mechanistically, both pharmacokinetically and pharmacodynamically, it is an unlikely candidate, and randomized controlled trials have either been retracted or are small and inconclusive, with variations from the published protocols.

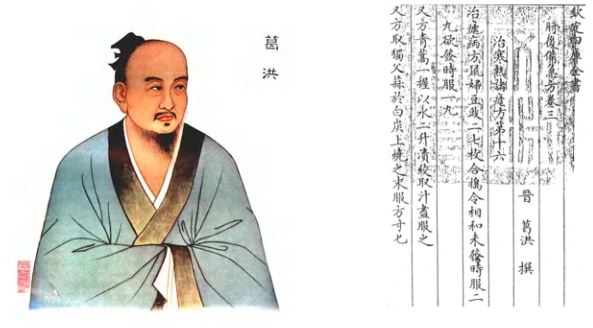

The other winner of the 2015 Nobel prize was the Chinese scientist Tu Youyou, who rediscovered a remedy for fevers, and specifically malaria, first described by the physician Ge Hong (284–363). In his treatise Emergency Prescriptions Kept up One’s Sleeve we find a recipe for preparing a drug from qinghao, the blue-green herb (Figure 2). Qinghao is the Chinese name for the plant we call Artemisia annua. The suffix –su means an active ingredient. So qinghaosu is an active ingredient extracted from the plant. Ge Hong had soaked the leaves of the plant in cold water and then wrung out the sap. Heat would have destroyed the labile active ingredients, which are cyclic endoperoxides, and the wringing out process is thought to have created an emulsion in which they were stable. Tu Youyou took note of Ge Hong’s method and isolated the active ingredient, now called artemisinin.

Figure 2. Ge Hong (284-363) and an extract from Emergency Prescriptions Kept up One’s Sleeve in Chapter 3, Section 16, “Prescriptions for treating intermittent hot and cold conditions and all kinds of intermittent fevers”: “Another recipe: take one bunch of qinghao, add two sheng of water, soak it, wring it out, take all of the juice, and ingest it”

The Artemisia genus includes several variants, such as Artemisia absinthium, which we call common wormwood, A. gallica (French wormwood), A. pontica (Roman wormwood), A. maritima (sea wormwood), and A. arborescens (tree wormwood). Artemisia is named after the Greek goddess Artemis, perhaps because it was used for obstetric or gynaecological purposes, with which she was associated, having supposedly helped her mother deliver her twin brother Apollo immediately after she herself was born. The origin of Artemis’s name is not known. If it was Greek, which it may not have been, it may have come from the word for a butcher, ἄρτᾰμος; Artemis, being a huntress, would have butchered the animals she killed. A similar word meaning safe or sound, ἀρτεμής, may reflect her virginity. Or, like Ares and Arethusa, it may contain a hint of ἀρετή, excellence or virtue. Or it may be from ἀρῐ-Θέμιϛ, comparing her favorably to the Titaness Themis, the goddess of divine law.

Wormwood supposedly grew in the trail of the biblical serpent (or worm) as it left paradise, and Culpeper recommended it for worms, among many other things, as did Mrs Grieve in The Modern Herbal. But “wormwood” actually comes from a mishearing or misspelling of “wermod”, listed in the Corpus Glossary of 725 as a gloss of the Latin word absinthium. This spurious connection between ivermectin, for worms, and artemisinin, from wormwood, is presumably not why the 2015 Nobel prize was shared out as it was.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.