Human behaviour will determine how quickly covid-19 spreads, say Susan Michie and colleagues

The UK government’s action plan on coronavirus issued today (3 March 2020) briefly mentions the role the public can play in supporting this response, including following public health authorities’ advice, for example on hand washing. [1] A consensus is emerging about the behaviours that members of the general population should be enacting to reduce their risk of contracting or spreading covid-19. [2] From experience in the 2009 H1N1 epidemic, the proportion of people routinely engaging in these behaviours is likely to be low. [3] A larger percentage claim to know about the required behaviours, but as has been well demonstrated, neither knowledge nor intention on their own lead to action. [4] Here we propose ways in which this “knowledge-action gap” can be reduced.

For any behaviour to occur, people need all three of: 1) capability, 2) opportunity and 3) motivation. [5,6] Capability involves psychological (e.g. the knowledge and skill to perform an action) as well as physical (strength and stamina) capability; opportunity involves both social (e.g. norms) and physical (e.g. resources) facilitators; and motivation involves both “reflective” (e.g. conscious decision-making) and “automatic” (e.g. emotion and habit) processes. These behavioural influences interact as shown below:

The COM-B Model (Capability-Opportunity-Motivation-Behaviour)

Given differences in behaviours and their contexts, the factors maintaining them differ as do the ways of changing them. A novel infectious disease outbreak presents a unique set of circumstances and challenges, and each recommended protective behaviour will vary according to changes in capability and/or opportunity and/or motivation that are required for them to be widely enacted. Understanding these influences is key to developing effective strategies to enable change.

The starting point for a successful behaviour change strategy is to state as clearly and specifically as possible what changes are required. We have started to do this for the current covid-19 outbreak. [2] However, it is also important to focus on a small number of key behaviours rather than long lists that people will struggle to remember and build into their everyday lives.

The COM-B model can help guide strategies to ensure that the capability, opportunity, and motivation are all in place when required. This involves the following broad strategies:

Capability: Learn how to enact the behaviours and practise them so that you perform them effectively.

Opportunity: Plan ahead so that you have everything you need when the time comes to enact the behaviour, giving yourself the opportunity to enact it.

Motivation: Make the required behaviours more attractive or less aversive. Build them into habits and routines so that they occur without having to think about them. Minimise social awkwardness by giving explanations as to what you are doing. Take advantage of social contacts to get feedback on the behaviours to help build habits.

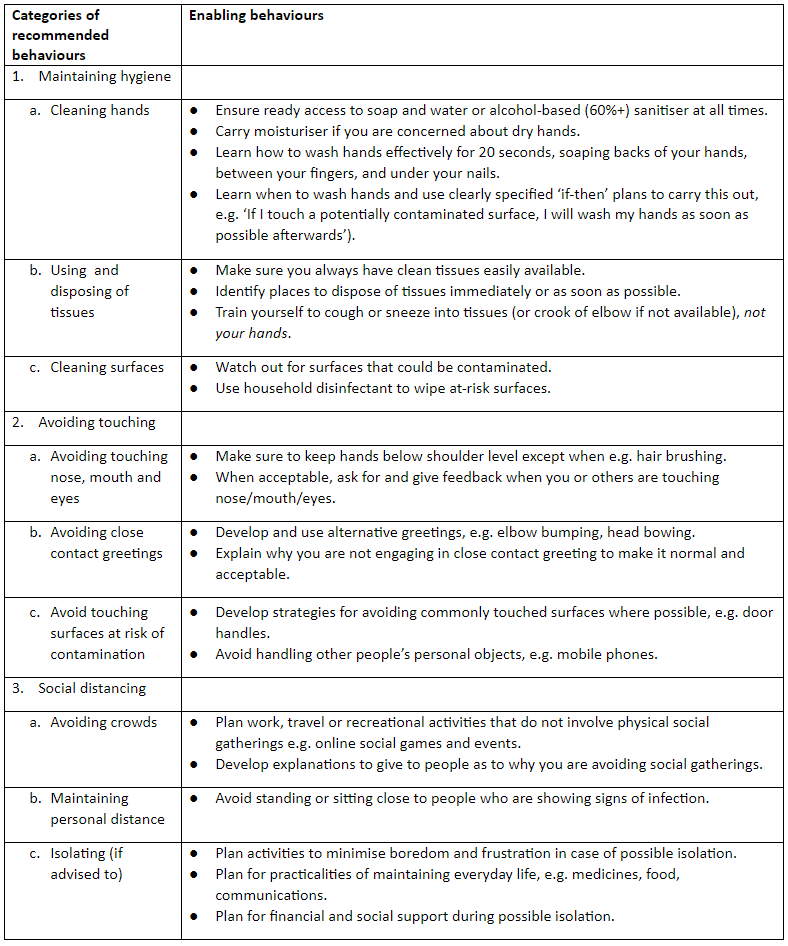

In Table 1, left-hand column, classifies into three groups the currently recommended behaviours with regards to the covid-19 outbreak for the general population to adopt in their everyday behavioural practices: maintaining hygiene, avoiding touching and social distancing (including isolation if advised). Within each category are three behaviours, making nine key behaviours in total. In the-right-hand column we list a set of enabling behaviours that we have developed using the COM-B model to help ensure that the key behaviours are enacted effectively when required.

Table 1. Categories of recommended and enabling behaviours to reduce COVID-19 transmission

To meet the challenges of the new behavioural and social changes that will help the population reduce the spread and impact of the COVID-19 outbreak, it is important ensure that people have the capability, opportunity and motivation to enact key behaviours. We are still learning how best to do this in relation to COVID-19, but some key principles are:

- practice developing the skills required,

- establish routines and habits,

- make the changes as easy as possible,

- make plans including how to overcome possible barriers to the behaviours,

- ask for support and feedback from family, friends and colleagues,

- if you are doing less of things you enjoy, try to find enjoyable alternatives.

And finally it is important that people feel positive about, and reward themselves for, their successes in making the necessary changes rather than dwelling on times when they slip up. [7]

Susan Michie is Professor of Health Psychology and Director of the Centre for Behaviour Change at University College London and a member of the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Behavioural Science (SPI-B): 2019 Novel Coronavirus (Covid-19)

Susan Michie is Professor of Health Psychology and Director of the Centre for Behaviour Change at University College London and a member of the Scientific Pandemic Influenza Group on Behavioural Science (SPI-B): 2019 Novel Coronavirus (Covid-19)

Robert West, professor of health psychology, department of Behavioural Science and Health, University College London.

Richard Amlôt is the head of the Behavioural Science Team, Emergency Response Department Science and Technology (ERD S&T) at Public Health England, and visiting professor of practice in the psychology of health protection at King’s College London.

Competing interests: None declared.

Role of funding source: Michie is affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research Behaviour Science Policy Research Unit at University College London. Amlôt is affiliated to the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit in Emergency Preparedness and Response at King’s College London, and Evaluation of Interventions at the University of Bristol, in partnership with Public Health England. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or Public Health England. The funders played no role in the writing of the manuscript of the decision to submit it for publication.

References:

- Coronavirus: action plan: A guide to what you can expect across the UK. Emergency and Health Protection Directorate, March 3, 2020.

- Michie S, Rubin GJ, Amlot R. Behavioural science must be at the heart of the public health response to covid-19. BMJ. February 28, 2020.

- Rubin GJ, Potts HWW, Michie S. The impact of communications about swine flu (influenza A HINIv) on public responses to the outbreak: Results from 36 national telephone surveys in the UK. Health Technology Assessment. 2010;14(34):183-266 doi:10.3310/hta14340-03.

- Webb TL & Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:249–268. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249.

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: a new method for characterizing and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science. 2011; 6: 42. doiI:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

- Michie S, Atkins L, West R. (2014) The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. London: Silverback Publishing. www.behaviourchangewheel.com.

- West R, West J (2019) Energise: The Secrets of Motivation. London: Silverback.