As I discussed last week, defining a drug shortage is problematic.

As I discussed last week, defining a drug shortage is problematic.

First, there is the problem of ambiguity—distinguishing poor supply from shortage. Supply problems can occur even when there are no shortages. But it is natural to talk about a drug being in short supply when you mean that there is a shortage, even though the two are not synonymous. The term “stock-out”, presumably introduced to avoid this problem, typically refers to the absence of a product from the shelves of an individual pharmacy, for example in a hospital or the community, without necessarily implying a shortage. However, it could also refer to a manufacturer or distributor, which might or might not imply a shortage.

Secondly, definitions, which should ideally include words that are easily understood, often refer to concepts that themselves need careful definition. For example, the definition proposed by a WHO review group included the word “essential”; but what is essential in one place is not necessarily so in another, and different people might define it differently. The current shortage of influenza vaccine is important in the UK, but not in the Antipodes.

Thirdly, the period over which the nonavailability of a product constitutes a shortage is poorly specified across the many proposed definitions, ranging from a day to a month. This in itself is unsatisfactory, but there is the added problem that the forgiveness of a medicine, a measure of the length of time a medicine can be omitted without loss of benefit, varies from medicine to medicine. Missing a few contraceptive pills may result in an unwanted pregnancy, whereas one can miss treatment with a statin for much longer without risk.

Definitions also vary according to who frames them. Legislative and regulatory definitions are framed for the benefit of legal systems and regulators. These are so-called stipulative definitions and they may not be helpful to individual patients during shortages.

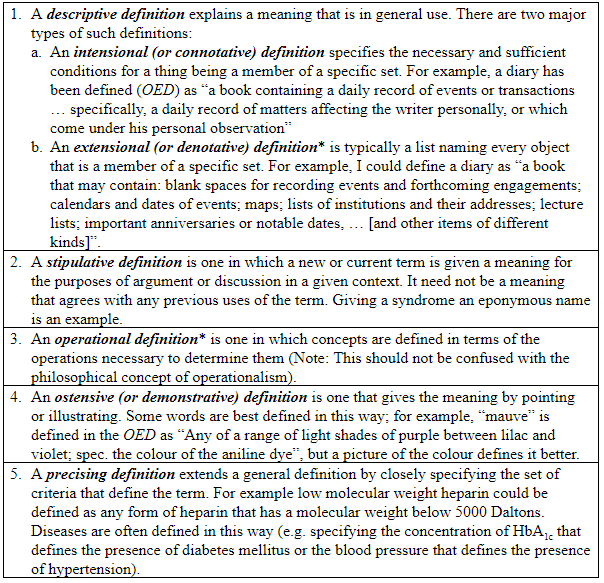

Perhaps it is not possible, as I suspect, to frame a satisfactory definition. But there are more ways than one of crafting definitions. I have described the major types in Box 1.

Box 1. Types of definition

*Extensional and operational definitions may be helpful in framing intensional definitions, which are typically the kinds of definitions that you will find in dictionaries (lexical definitions)

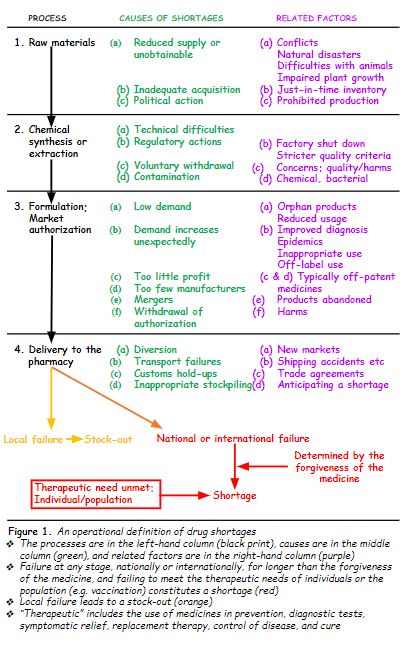

So, I have constructed an operational definition. First, I enumerated the main processes whereby a medicinal product is manufactured and finally delivered to the patient: obtaining the raw materials, synthesis or extraction of the chemical, formulation of the authorized pharmaceutical product, and delivery to a pharmacy, either directly or via a distributor.

Then I added the main causes that have been described and related factors. Finally, I indicated the two main outcomes of failure in the system. Failure at any level, if it affects availability only locally, results in a stock-out; national or international failure at any level that cannot meet the patient’s individual therapeutic needs or the population’s needs, when the forgiveness of the medicines is shorter than the duration of the failure, results in a shortage. The definition is shown below (Figure 1).

The WHO definition that I cited last week stipulates that a medicine must be essential for a shortage to be declared, but does not define “essential”. Similarly, the 2012 US Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA) stipulates that a medicine should be “life-supporting”, or “life-sustaining”, or “intended for use in the prevention or treatment of a debilitating disease or condition”. The first two terms have been defined as follows: “Life supporting or life sustaining means a product that is essential to, or that yields information that is essential to, the restoration or continuation of a bodily function important to the continuation of human life.”

This stipulation serves the purposes of the act and reflects actions that the regulator and manufacturers should take (e.g. giving advance warning of an expected shortage), but patients might be forgiven for thinking that the definition of a shortage should not be limited to such medicines. A medicine that was useful for treating, say, attacks of migraine, would not be encompassed by this definition, but patients who suffer severe frequent attacks and find themselves unable to obtain such a medicine during a shortage would be entitled to feel that their medicine ought to be included and dealt with in the same way as other medicines.

The operational definition that I have outlined here does not contain such restrictive stipulations.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.