Over the last four weeks I have been discussing drug shortages, their history, causes, harms and errors that can result, and proposed solutions. But defining a drug shortage is not easy.

Over the last four weeks I have been discussing drug shortages, their history, causes, harms and errors that can result, and proposed solutions. But defining a drug shortage is not easy.

I have found two systematic reviews of definitions. The first listed 18 general definitions of a shortage plus eight definitions describing drugs for which shortages are reported; the second, a WHO review, listed 56 statements of various kinds described as definitions. However, many of the so-called definitions listed in these reviews are not definitions at all (see Box 1). The WHO reviewers recognized this: “Some papers described conditions or systems in which an action was required to address a shortage or stockout, in which case these descriptions were taken to be definitions.” Even though they are not.

Box 1. Principles underlying the formulation of a good definition

|

Combining the two lists and adding other definitions that I have found, I have compiled a list of 43 descriptions in all. There is no general agreement as to what constitutes a shortage. Furthermore, some terms need to be separately defined and others need careful consideration.

Supply Of the 43 descriptions, 22 include the word “supply”, in terms such as non-supply, supply disruption, supply chain, supply problems, [in]appropriate and [non]continued supply, inadequate supply, and supply issue (i.e. non-issue). You might think that inadequate supply of a medicine constitutes a shortage. However, an individual pharmacy may run out of a medicine which is generally available elsewhere.

Stock-out This term, which alludes to the absence of a medicine from the pharmacy shelves, appears in 13 of the 43 texts. It is variously defined as an inability of a pharmacy to deliver a drug to a patient, zero usable stock, complete absence of a medicine in stock, no medicine facility shelf, and absence of a medicine at a health facility level; in at least one specific case it is defined as either a complete absence or a certain minimum level of stock for a given duration. But again, a local absence of stock need not imply a general shortage.

Pharmacy Different terms are used to qualify the term “pharmacy” (e.g. community, hospital, dispensary, internal use, and health facility pharmacy).

Patients Only 18 of the 43 texts specifically mention patients, and none mentions effects on public health. Phrases used include: problems with continued treatment, detrimental consequences, affecting patients’ ability to access required treatment, compromising or influencing or impacting on patient care, [failure to] meet/comply with patients’ needs, [failure to] meet current projected demand at the patient/user level, and [failure to] meet expected patient volumes. In these paraphrases, I have added the bracketed word “failure”, since no definition mentions it, even though we are talking about a failure to meet patients’ therapeutic needs.

Duration Different definitions offer different time courses over which a medicine cannot be obtained in order to define a shortage: at least one day, three days, four days, 14 days, 20 days, or at least one month; some are more vague: “every delay in monthly supply” or “within a few days”. However, different delays affect different medicines differently. For example, even a delay of a day in supplying an oral contraceptive may be deleterious, while other medicines can be missed for longer periods. This concept has been referred to as “forgiveness”, a measure of the length of time a medicine can be omitted without loss of benefit.

Specificity Some definitions, particularly those included in legislation, refer to a specific country. Some refer to specific diseases. Only two take in a wider purview, referring to local, national, and international shortages, and both of those derive from the same original source.

In Box 2 I have listed some of the general problems with the definitions that have hitherto been suggested. The WHO reviewers proposed the following definition of a drug shortage: “The supply of medicines, health products, and vaccines identified as essential by the health system is considered to be insufficient to meet public health and patient needs.” This definition, probably deliberately, leaves some things unsaid. For example, it does not define “essential”. And there is also the lexicographical problem that this is not strictly speaking a definition, but a “when” description that omits the word “when” (Box 2).

I shall try to tackle these problems next week.

Box 2. Some general problems with published definitions of a drug shortage

|

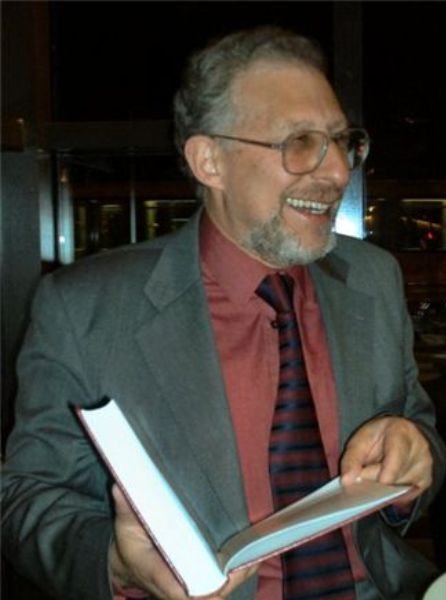

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.