Much has been written about so called “heart sink” patients, but Jonathan Glass says what doctors need to avoid is becoming the heart sink doctor

Every Friday morning in our department we have an academic meeting, lasting an hour. My colleague Tim O’Brien plans, organises, and runs our weekly gatherings and next month we will be celebrating our 1000th Friday meeting. They are a highlight of the departmental week.

Every Friday morning in our department we have an academic meeting, lasting an hour. My colleague Tim O’Brien plans, organises, and runs our weekly gatherings and next month we will be celebrating our 1000th Friday meeting. They are a highlight of the departmental week.

Occasionally we have a “round the room” session, where each of the consultants present spends a couple of minutes discussing how they approach a particular patient group—for example, men with erectile dysfunction or women who’ve had recurrent urinary tract infections. This week the subject was our experiences with what has been termed the “heart sink” patient. Each of us was supposed to talk about cases that we’ve found difficult, whether it was a patient with a particularly challenging condition or a puzzling set of symptoms, likely to be organic in origin. It’s those cases that cause the doctor to hold their head in their hands while they generate the mental strength to call the patient into the clinic room. Patients with pelvic pain and men with prostatitis were discussed, along with similar difficult clinical scenarios that you’d expect to be troubling the doctors in a urology department.

I thought a lot about the idea of the heart sink patient before creating the one slide (see further down) I prepared for my contribution. The kind of person who fits the description of what doctors mean when they talk about the heart sink patient has often engaged with healthcare many times in their lives. They’ve seen the ENT surgeon about their sinus problems, been diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome by the gastroenterologist, discussed their headaches with the neurologist and their heavy periods with the gynaecologist. They are familiar with how the healthcare system works, they are used to seeing the junior doctor in clinic, and are often sent around the houses to different specialists.

This made me reflect on what we’re doing wrong as healthcare professionals when we see these patients. My suspicion is that these patients are often met in clinics by what they might consider to be the “heart sink doctor.”

They will know the doctor I’m talking about: the unengaged doctor who has no interest in the patient. The doctor who is seeing a patient while they are thinking about what they are doing at the weekend or whether they are going to make it to their kid’s parent’s evening, or who has become disillusioned with the job they thought they had signed up to 30 years ago when they left medical school. Don’t think the patient doesn’t spot you—they are likely to be adept at recognising the heart sink doctor almost as soon as they walk in.

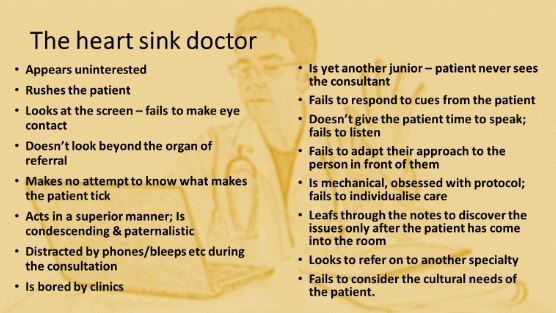

What defines the heart sink doctor? Well, that was the content on my single slide.

Heart sink doctors arrive in clinic bored and uninterested. They try to rush the consultation and are distracted during it by their phone or their bleep. They don’t make eye contact with the patient—their focus is directed to the computer screen. They make no attempt to discover anything more about the person in front of them other than their presenting symptoms by failing to ask about what makes them tick, what drives them. They are condescending, superior, and paternalistic and do not respond to any cues that the patient or their relatives might offer.

They leaf through the pages of the notes while the patient is in front of them, having not done so before the patient entered the room. They listen poorly, and don’t give the patient time to speak or voice their concerns. They fail to adapt their language and responses to the needs of the individual in front of them and don’t recognise any cultural concerns that might be pertinent to the patient and their family. They are protocol driven and fail to individualise the care they offer. They are looking to refer the patient on to another specialty at the earliest opportunity.

I understand how we can all fall into the trap of becoming such a doctor. The demands placed upon us by the healthcare system are endless. In my first ever ward round as a doctor, my consultant, Paul Abel, said to me, “Jonathan, today you will be given a list of things to do; you will never finish it.” He was right. Our challenge, however, is to give patient number 11 in a clinic the same freshness as patient number one.

It can be hard to put away all of our other stresses and focus on just the individual in front of us at that moment. But we should never forget that we are in the remarkable position of being given a window on the lives of so many fascinating individuals. If we can maintain the enthusiasm of having that privilege, it will help us continue to deliver high quality frontline care to those patients whose cases challenge us. The so called “heart sink patient” may, in fact, need our time the most. We need to avoid becoming the heart sink doctor.

Jonathan Glass is a consultant urologist at Guy’s & St Thomas’s Foundation Trust. Twitter @JMG_urology.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: None.