Today’s challenges lie in non-communicable diseases—a development that calls for political commitment at the highest level

The World Health Organization was founded in 1948 with a simple but bold vision: the highest attainable standard of health for all people.

The World Health Organization was founded in 1948 with a simple but bold vision: the highest attainable standard of health for all people.

Importantly, the writers of WHO’s constitution affirmed that health is not merely a luxury to which states should aspire, but “one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.”

For more than 70 years, WHO, its member states, and partners have worked towards that goal. There are considerable achievements to be proud of: global life expectancy has increased by 25 years; maternal and childhood mortality has plummeted; smallpox has been eradicated and polio is on the brink; we have turned the tide on the HIV/AIDS epidemic; deaths from malaria have dropped dramatically; and new vaccines have made once feared diseases easily preventable.

Many of these achievements, especially during the era of the Millennium Development Goals, are thanks to concerted efforts against some of the world’s leading causes of death and disease.

But changing patterns in demographics, economics, and politics bring changing patterns in health. Communicable diseases have now been replaced by non-communicable diseases as the world’s leading killers. Antimicrobial resistance threatens to roll back a century of medical progress. Climate change and pollution are posing new health threats.

These developments have given rise to the dawning realisation that “the highest attainable standard of health” cannot be achieved one disease at a time. Although disease specific programmes will always be necessary, they must be built on the foundation of integrated and people centred health systems that address the full range of health needs for individuals, families, and communities.

All people, regardless of who they are or where they live, must be able to access high quality essential health services, without suffering financial hardship.

These three ideas—access to health services, with financial protection, equally for all—are the essence of universal health coverage.

By each of those measures, we have a lot of work to do.

More than half the world’s population lacks access to essential health services, including vaccination, the ability to see a health worker, or access to treatment for HIV.

Even when services are available, using them can spell financial disaster. Every year, almost 100 million people are pushed into extreme poverty by the costs of paying for care out of their own pockets.

Universal health coverage does not mean that every country must provide free access to every conceivable health service or health product. All countries must make tough decisions about what to cover, based on the resources they have.

Most health funding needs to come from domestic sources. Smart governments are increasingly attuned to ways to do this, including through increased taxation on tobacco and other unhealthy products such as sugar sweetened beverages. Raising prices on tobacco and alcohol and increasing excise taxes reduces consumption, saves lives, and generates additional revenue that countries can reinvest in health.

In all countries, the bedrock of universal health coverage is strong primary health care, with an emphasis on promoting health and preventing disease. In the Declaration of Astana, all countries have committed to investing in primary healthcare.

Universal health coverage is not just the best investment in healthier populations. It is also the best investment in health security. Strong health systems are better able to prevent, detect, and mitigate outbreaks.

The benefits of universal health coverage go far beyond health. Universal health coverage reduces poverty by removing one of its causes, creates jobs for health professionals, improves productivity, and stimulates inclusive economic growth because healthy people are productive people, and improves gender equality because it is often women who miss out on health services. In that sense, universal health coverage is an engine of sustainable development.

I know from my own experience in government, and as director general of WHO, that the key to making real progress towards universal health coverage is political commitment at the highest level, with the support of parliaments to translate that commitment into law, backed by a whole of government approach that addresses the commercial, economic, environmental, and social determinants of health.

At this year’s United Nations General Assembly, world leaders will meet for the first High Level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage, with the theme of “moving together to build a healthier world.”

This is a crucial opportunity to catalyse political leadership that can transform the lives of billions of people.

Many G20 and G7 countries are the standard bearers for universal health coverage with decades of experience under their belts, while others are at the vanguard of a new wave of countries that are making bold strides towards it. Together, these countries are uniquely positioned to provide strong leadership for others to follow, and to demonstrate that health is a political choice that all countries can make.

First published in Health: A Political Choice, an official Global Governance Project publication, edited by John Kirton and Ilona Kickbusch. Read your copy here www.bit.ly/2019UHC

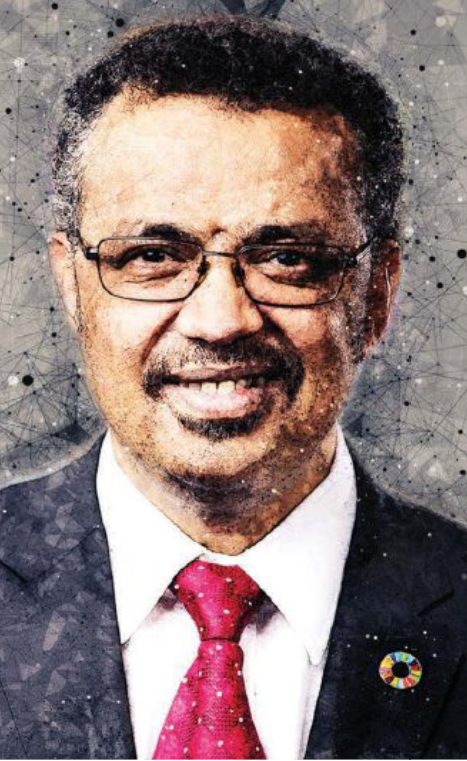

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus is director general of the World Health Organization, was elected in 2017, and was the first person from WHO African Region to serve as WHO’s chief technical and administrative officer. Dr Tedros served as Ethiopia’s minister of foreign affairs from 2012 to 2016 and minister of health from 2005 to 2012. He was elected chair of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria Board in 2009, and previously chaired the Roll Back Malaria Partnership Board, and co-chaired the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Board. Twitter: @DrTedros