We need to do more to tackle these issues and highlight the diversity of our workforce to prevent this kind of discrimination in the future, says Alexandra Adams

A silent problem is sweeping through NHS hospitals across the country. It not only affects our patients, but it affects our staff too—physically and mentally. It is widespread and very hard to treat. It is silent because we are all too scared, and singled out, to do or say anything about it. And for those who aren’t affected by it, we are otherwise oblivious to it even being there in the first place. It is lingering around far more than you think. It is workplace discrimination.

For those of you who can remember your first day on an NHS ward, I hope it brings back good reflections. Nervousness, uncertainty, bewilderment—yes, but also excitement, satisfaction, hope, reward, and optimism for a future career as an NHS employee. My experience of my first day could not have been more different. I came home that day with an entirely new perspective on my workplace. And it wasn’t the greatest of perspectives either.

I have severe visual and hearing impairments. When I arrived on the ward, a doctor turned round to me and saw my white cane and asked, what I was doing with the patient’s cane. I had to point out, apologetically, that the white cane was, in fact, mine. I was then told in front of my medical student colleagues, in front of the staff on the ward, and in front of the patients that I was not allowed to touch any of the patients—I felt disgusting. In the heat of the silence, I asked if I was at least able to observe some clinical skills and to look through some of the patients’ X-rays, only to be told that I couldn’t. I was asked to “imagine you’re a patient. Would you want a disabled doctor treating you? Absolutely not!” I was left not quite knowing what to do. Shortly afterwards I was sent home.

That was my first day on clinical placement as a third year medical student. I came home, seriously contemplating, for the first time, whether medicine was really for me or not. This was not what being a doctor was about. This was not what I had signed up to do medicine for. But what I had failed to realise was that, on that first day, I had experienced workplace discrimination—and I wasn’t even a qualified doctor yet.

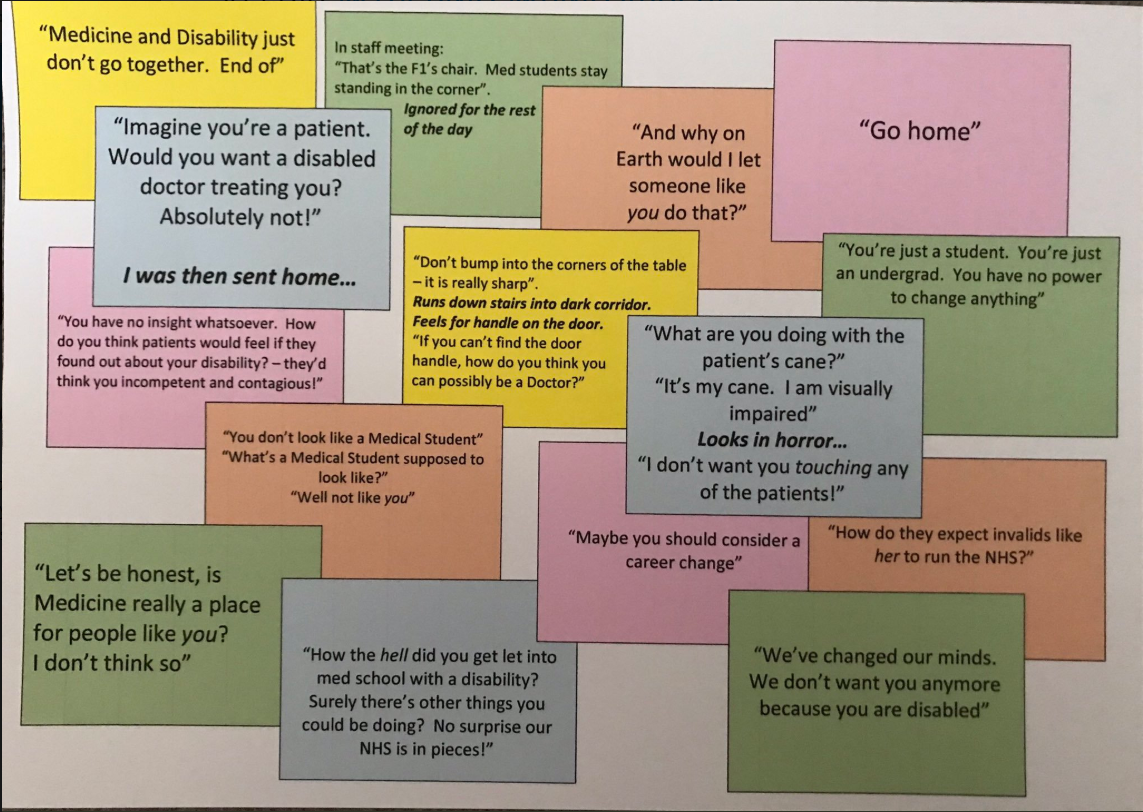

When the discrimination I faced as a medical student became more frequent on placement, I was advised to start writing it all down, recording the comments

I have often been asked by colleagues whether I think there’s any discrepancy between discrimination and bullying. Legally these are treated as separate issues with clear definitions. But in my view, there is an overlap between discrimination and bullying, and we should not be allowed to get away with either. Those who are discriminated against feel bullied, and those who are bullied are discriminated against.

There have been many conversations on how the system is partly to blame for this. Doctors cannot care for their patients, if the system doesn’t care for them, and if healthcare staff don’t treat each other with care or respect. Without that care or respect for each other, we can’t “work with colleagues in the ways that best serve patients’ interests”. And the worst thing is when our patients notice. When I have been discriminated against because I have a long white cane and wear hearing-aids—the patients saw. When colleagues have deliberately ignored my questions, yet answered the other medical students—the patients saw.

I have experienced discrimination both inside my medical career and outside, and in many ways I have accepted that I will most likely experience an element of it throughout my whole career. But it’s getting the balance between accepting that this is just another day of misunderstanding, or social ignorance, and knowing when this tips over into discrimination or bullying. There are a lot of issues that we can’t see in our workplace, and bullying is just one of them. Whether that’s because we are ignorant to it happening, or just oblivious, or whether it is the fault of an individual or of an overall system. But what we all know is that it is not acceptable, and is most definitely not welcome in our NHS.

My experiences of discrimination and workplace bullying so early on in my medical career has been one of the many inspirations behind starting up a campaign, “Faces of the NHS.” I am making my way around the UK collecting portraits and stories of many NHS employees; past, present, and future, with the aim of celebrating our diversity and differences, and to show that these differences in our backgrounds, motives, and external characteristics, should be embraced, respected, and treasured, not stigmatised, stereotyped, or insulted. While the finished result will hopefully have a positive impact, a campaign like this takes time, and admittedly will not, and cannot, fully address all these outstanding issues imminently.

In the meantime, we need to raise awareness of workplace discrimination and bullying among staff by opening up more, and offering our colleagues the opportunity to disclose their experiences, so that we can fight back and clamp down on those who are still driving this culture. Collating together more of the negative comments, both verbal and physical, that our NHS staff have faced, just like the one I began compiling, could be one way forward in highlighting this. And just like the standard, big red Sepsis and Flu posters, the distribution of staff well-being posters, like an “Are You Okay” campaign, may be just what’s needed to remind us all that it’s okay to speak up against bullying and discrimination. After all, words inflict actions, and kindness kills.

I may not have as much eyesight as most, but my experience has given me more insight into what discrimination and bullying is than many. Like many disabilities, many mental health illnesses are not visible, and it’s the invisible struggles of our employees that continue to go unnoticed, ignored, and unrecognised. We need to do more to tackle these issues and highlight the diversity of our workforce to prevent this kind of discrimination in the future.

Alexandra Adams is a medical student with severe visual and hearing impairments and the founder of the Faces of the NHS social photography project.

Competing Interests: none declared.