Desmond Laurence (1922–2019), one of the founders of UK clinical pharmacology, died this week. Others, better qualified than I am to do so, will write obituaries. But I should like to pay a tribute to Desmond, by highlighting his influential textbook, Clinical Pharmacology.

Clinical pharmacology was originally known as “materia medica”, the Latin translation of the title of a five-volume text by the Greek herbalist and physician Pedanius Dioscorides, written in 50–70 AD, called Περί ύλης ἰᾱτρικής, literally “about medical stuff”, “De materia medica” in Latin. The earliest surviving version is the 6th century Codex Vindobonensis.

“The materia medica” in English originally meant “the remedial substances and preparations used in the practice of medicine [or] a list of these” (OED). It was first recorded in Philip Skippon’s journal, dated 1663, in which he described “four hundred glass bottles filled with the Materia Medica, chmymically prepared”.

Then, in the 18th century it came to mean “the branch of medicine that deals with the origins, preparation, and use of the materia medica”, as recorded in Tobias Smollett’s picaresque novel Humphry Clinker (1771): “There are different courses for the theory of medicine, and the practice of medicine; for anatomy, chemistry, botany, and the materia medica, over and above those of mathematics and experimental philosophy.”

Textbooks of materia medica started to appear in the late 18th century. They included Methodus Materiae Medicae (1770) by Francis Home, the first Professor of Materia Medica in Edinburgh (as opposed to Botany and Materia Medica, an earlier chair); Materia medica Americana, potissimum regni vegetabilis by Johann David Schöpf (1787); A Treatise of the Materia Medica (1789), by William Cullen, Professor of Medicine in Edinburgh; Elements of Therapeutics & Materia Medica by Nathaniel Chapman (1821); Elements of Materia Medica & Therapeutics by Anthony Todd Thomson (two volumes, 1832 and 1834); and Elements of Materia Medica & Therapeutics by Edward Ballard & Alfred Baring Garrod (1845).

So when the physician John Mitchell Bruce wrote his textbook on the subject, first published in 1884, he called it Materia Medica and Therapeutics. An Introduction to the Rational Treatment of Disease. Bruce was joined, in 1912, for the 9th edition, by the clinical pharmacologist Walter J Dilling. Dilling became the sole author of the 15th edition in 1939 and continued as such until the 19th edition, published posthumously in 1951.

When Stanley Alstead, Regius Professor of Materia Medica in Glasgow, who taught me materia medica, with his colleague J Gordon MacArthur, produced the 20th edition of Dilling’s textbook in 1960, they called it Dilling’s Clinical Pharmacology. Desmond’s Laurence’s textbook, Clinical Pharmacology, was first published in 1960. I know of no earlier books similarly titled, although John Taylor Halsey’s translation of a German text as Pharmacology, Clinical and Experimental (1914), comes close.

As a student at Glasgow University in the 1960s, I used Dilling’s textbook. I learnt about Desmond’s book only when I came to Oxford in 1973 and discovered that the jokes in it were much better than those in Dilling. [Actually, there were no jokes in Dilling.] Peter Kneebone’s illustrations, in the second and later editions of Laurence, added to the fun.

Left: The cover of Desmond’s 1959 publication, in which “human pharmacology” and “clinical pharmacology” were contrasted by Harry Gold.

Middle: The cover of the 21st edition of Clinical Pharmacology (Dilling), the textbook I used as an undergraduate; Stanley Alstead became Regius Professor of Materia Medica in Glasgow in 1948

Right: The title page of the first edition (1960) of Laurence’s Clinical Pharmacology, co-authored with Moulton; the reviewer in the BMJ, C A Keele, wrote “This is a very good book. … I recommend [it] highly”

The earliest instance of the term “clinical pharmacology” that I have found is from 1901 in the BMJ, but it became fashionable only many years later.

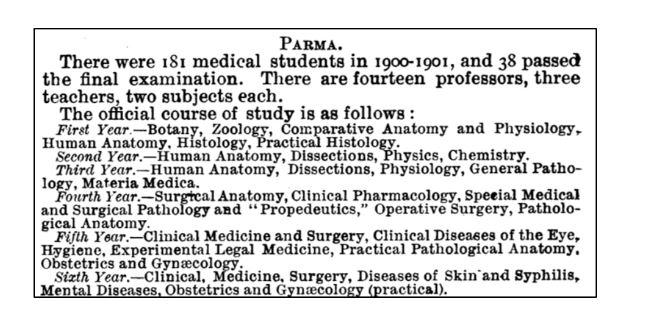

Pharma in Parma. The earliest instance that I have found of the term “clinical pharmacology” (Burton-Brown FH. Medical Education In Italy. Br Med J 1901 Dec 14; 2(2137): 1751-4); in this survey, the names of the subjects taught in various Italian schools were presumably translated from the Italian

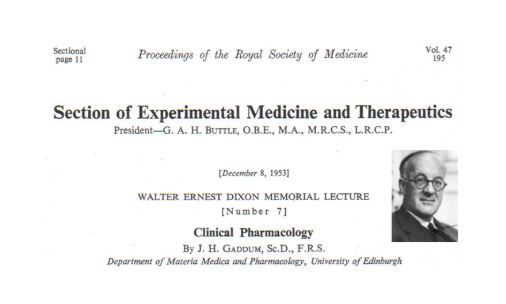

Desmond worked in the Department of Applied Pharmacology at University College Hospital in London, and in 1959 he titled the proceedings of a meeting that had been held in London the previous year, Quantitative Methods in Human Pharmacology and Therapeutics. However, John Gaddum had titled his 1953 lecture to the Royal Society of Medicine “Clinical Pharmacology”, and Harry Gold, who had been Professor of Clinical Pharmacology at Cornell since 1947, reminded UK pharmacologists of that fact in his paper in Desmond’s 1959 book. Perhaps that’s why Desmond used the term for the title of his new textbook.

John Gaddum’s Walter Ernest Dixon Memorial Lecture (1953): “I propose to discuss some of the clinical implications of pharmacology. I had already decided that the title of my lecture would be ‘Clinical Pharmacology’ when I found that Dr Harry Gold (1952) had used the same words to describe the same thing” (Proc R Soc Med 1954; 47(3): 195-204)

Harry Gold (1889-1972), First Professor of Clinical Pharmacology, Cornell, 1947; “[At Cornell] we call [the subject] clinical pharmacology. Many of you are probably familiar with Dr Gaddum’s Dixon Memorial Lecture on this subject under the title, ‘Clinical Pharmacology’ But I believe your term, “Human Pharmacology”, is a better one, free of the various meanings of the term ‘clinical’, which tend to identify it with the art of therapeutics, the practical care of patients.” The term “clinical pharmacology” probably prevailed because UK clinical pharmacologists were very much concerned with the practical care of patients.

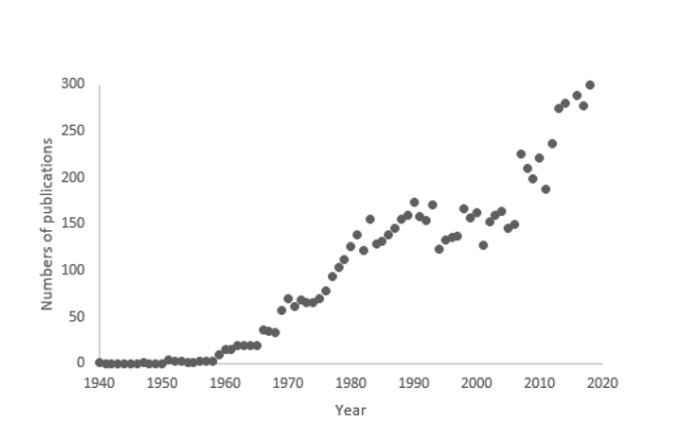

The growth of clinical pharmacology since the 1960s is reflected in the relevant publications and was partly driven by its textbooks. Clinical Pharmacology inspired many students to become clinical pharmacologists, as Dilling’s textbook inspired me.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.