A few weeks ago I discussed finger counting, fingerprints, and the words we use to name the digits of the hand, starting with the thumb. Now the index finger.

A few weeks ago I discussed finger counting, fingerprints, and the words we use to name the digits of the hand, starting with the thumb. Now the index finger.

The word “index” comes from the IndoEuropean root DEIK, meaning to show or to utter, which I have discussed in detail before. DEIK gives us many different words, including deictic proofs and apodictic statements; paradigms, lost and found; dictation, diction, and dicta; addicts and verdicts; edicts and interdicts, contradictions, predictions, and jurisdictions; benediction, malediction, and valediction; abdicate, dedicate, syndicate, and predicate, predicament and preach. And not forgetting vindictiveness.

DEIK also gives the Greek word δάκτυλος, a finger, in classical Latin digitus. So the Latin digitus index, the index finger, comes from DEIK twice over.

In Latin index meant one who reveals something or an informer, a marker or indicator, the title of a book, a summary or digest, and a list or catalogue, all different kinds of pointers. In English, from the late 14th century, the index finger was simply called the index or the first finger. Later it also came to be called the forefinger, a word that dates from the 15th century.

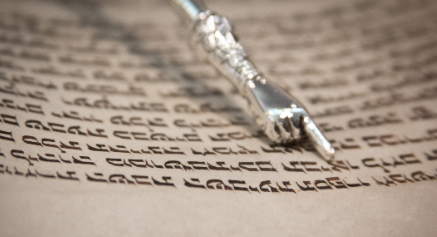

Then “index” came to mean anything that pointed, such as the hand of a clock or the gnomon of a sundial, and, because of a fanciful resemblance to the latter, the nose. The pointer used by anyone who is reading from the sacred scroll of the Hebrew Torah, known as a yad (יד), a hand, is made in the shape of a hand with the index finger extended (Figure 1). Dating from the mid-19th century, the index finger has also been called the pointer finger. And as the late François Caradec pointed out in his Dictionary of Gestures, the index finger is capable of more than 60 types of gestures, with different meanings in different cultures.

Figure 1. Reading the scroll of the Hebrew Torah with the help of a yad; the reader, who declaims the text aloud to the congregation, may hold the yad, or it may be held by a representative of the congregation, a segal, originally a deputy high priest; it is not permitted to touch the parchment, which makes one ritually impure and risks damaging either the parchment itself or the ink, which sits on the surface of the vellum; a typical yad is about 12 inches long and made of silver

Then, in the late 16th century, an index became an alphabetical list of the contents of a book. “The Index”, short for Index librorum prohibitorum, was a list of books that Roman Catholics were forbidden to read, formulated by the Council of Trent and published by the authority of Pope Pius IV in 1564. The Council also formulated an Index expurgatorius, which specified the passages that were to be expunged from works that one was otherwise allowed to read.

Also in the late 16th century, index came to mean something more abstract, a guiding principle.

A mathematical index, first mentioned in the late 17th century, is a symbol, usually a number, placed above and to the right of a quantity, also called an exponent. This can be seen in lines from a poem by Lewis Carroll, called “Four Riddles”:

Yet what are all such gaieties to me

Whose thoughts are full of indices and surds?

x2 + 7x + 53 = 11/3

Those who want to try solving the equation can use the method that I have previously described; for those who don’t, x ≈ 3.5 ± 6.1i, where i is the square root of minus one.

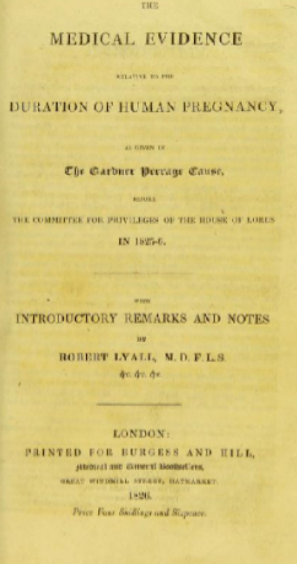

Surprisingly, the earliest instance of the term “index finger” recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary dates from as late as the mid-19th century, the citation being from William Makepeace Thackeray’s novel Pendennis (1848): “Jeames simply pointed with his index finger to the individual.” However, earlier instances can be found. The earliest that I have discovered happens to be medical. It comes from a pamphlet titled “The medical evidence relative to the duration of human pregnancy …” (1826; picture): “‘In examining,’ says Dr. Collins, ‘per vaginam, I found the neck, or cervix of the uterus, remarkably high, scarcely tangible, and with difficulty distinguished from the body of the uterus, as it presented little or no prolongation. Availing myself of my position, I placed the left hand on the abdomen, and giving a gentle jerk to the os tineae with the index finger of the other, the fœtus [sic] bounded from the touch, and fell again on the finger, exciting the sensation which the French call BALLOTMENT, and that degree of weight which a fœtus of eight months, it is supposed, could alone produce. Thus I ascertained the stage of the pregnancy …’” (page xix).

Surprisingly, the earliest instance of the term “index finger” recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary dates from as late as the mid-19th century, the citation being from William Makepeace Thackeray’s novel Pendennis (1848): “Jeames simply pointed with his index finger to the individual.” However, earlier instances can be found. The earliest that I have discovered happens to be medical. It comes from a pamphlet titled “The medical evidence relative to the duration of human pregnancy …” (1826; picture): “‘In examining,’ says Dr. Collins, ‘per vaginam, I found the neck, or cervix of the uterus, remarkably high, scarcely tangible, and with difficulty distinguished from the body of the uterus, as it presented little or no prolongation. Availing myself of my position, I placed the left hand on the abdomen, and giving a gentle jerk to the os tineae with the index finger of the other, the fœtus [sic] bounded from the touch, and fell again on the finger, exciting the sensation which the French call BALLOTMENT, and that degree of weight which a fœtus of eight months, it is supposed, could alone produce. Thus I ascertained the stage of the pregnancy …’” (page xix).

It is unlikely that there are not earlier instances still.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.