How to reap the benefits of new technologies while keeping a tight rein on healthcare costs is a challenge all countries face, not least China. It spends a relatively modest 6.2% of GDP on health, but expenditure has been rising rapidly and is poised to soar further for its population of 1.39 billion is ageing and rates of non communicable disease increasing.

How to reap the benefits of new technologies while keeping a tight rein on healthcare costs is a challenge all countries face, not least China. It spends a relatively modest 6.2% of GDP on health, but expenditure has been rising rapidly and is poised to soar further for its population of 1.39 billion is ageing and rates of non communicable disease increasing.

In response China has set up a new National Center for Medicine and Health Technology Assessment to inform decisions on which of the many new drugs, devices, and diagnostics coming on stream should be included in the country’s basket of care.

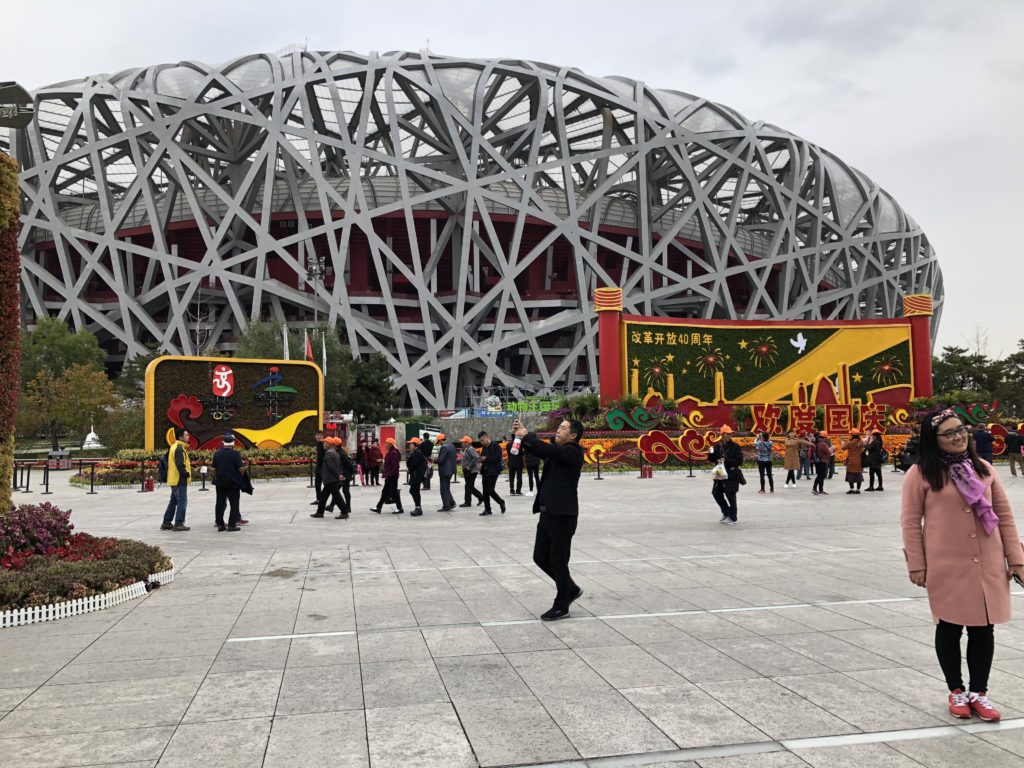

China’s determination to realise a health dividend from its investment in new technologies was the central message communicated at the country’s first Health Technology Assessment conference, which was held two weeks ago in Beijing. The venue was the capital’s impressive new conference centre, a stone’s throw from the 2008 Olympic games park with its iconic bird’s nest stadium (pictured right). Speakers were heralded to the podium with flashing lights and loud music, redolent of victorious athletes, but the mood was more cautionary than celebratory.

China’s determination to realise a health dividend from its investment in new technologies was the central message communicated at the country’s first Health Technology Assessment conference, which was held two weeks ago in Beijing. The venue was the capital’s impressive new conference centre, a stone’s throw from the 2008 Olympic games park with its iconic bird’s nest stadium (pictured right). Speakers were heralded to the podium with flashing lights and loud music, redolent of victorious athletes, but the mood was more cautionary than celebratory.

With a life expectancy of 76.7 years and a maternal mortality rate of 19.6 per 100 00, “our health indicators are not bad,” said Wei Fu, director general of the China National Health Development Research Center, “but we are challenged by limited resources and a large population.” And (as others observed) out-of-pocket expenses for patients are already high. The new national Health Technology Centre will guide regional policy and ensure that “priority setting is based on value,” she said. The assessment of new medicines will be a major component of the centre’s work and “inform decisions on what goes on the national essential medicines list.”

The high costs of cancer drugs, particularly immunotherapies, was flagged by several speakers, but as Fu underlined, one of the advantages of being a big country is that it increases bargaining power. “We have been able to negotiate [down] drug prices for 17 new cancer drugs,” she said.

As befits an inaugural meeting of a new body a plaque was unveiled, but the groundwork of the centre has already been established. Its health technology assessment network has 48 member institutions, and workshops and seminars have been held in 31 provinces. The centre has support from the Gates Foundation and World Health Organization, and has had teaching input from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and Imperial College London.

The weakness of the evidence on the clinical and cost effectiveness of new cancer drugs was another message repeated during the meeting. Most data are derived from short term, poorly controlled trials, conducted in unrepresentative populations, during which treatment is often switched; added to which there is a paucity of quality of life data, said John Cairns, a health economist from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Keeping the regulatory bar high and looking at impact on the overall health budget, as well as cost effectiveness, will be essential.

A reminder that countries’ health outcomes bear little relation to their health spend came from Kalipso Chalkidou, director of global health policy at the Center for Global Development. She also warned that “20 -40 % of expenditure on healthcare is wasted.” Countries must use health technology assessment as a policy tool to contain spending and drive more equitable care, she said. The evidence generated also helps negotiate prices and rules on reimbursement, and “China can lead the way here.”

Maarten Ijzerman, chair of cancer health services research at the University of Melbourne, urged China to focus on the whole delivery system for cancer care. “It’s not all about the drugs,” he said, “which rarely show benefits on overall survival or quality of life in randomised trials.” Value based healthcare should be defined by delivering outcomes that matter to patients, and the cost of delivering those outcomes over the full cycle of care.

The part that patients should play in assessing the value of new technologies was also debated and clearly needs development, for as Guoen Liu, director of the Peking University China Center for Health Economic Research, admitted, “the patient is not [at present] in the equation.”

The new China Health Outcomes Research Alliance, which was launched at the Beijing meeting, is set to redress this. It will conduct research and collate data on patient reported outcomes and experience to feed this into debate and decisions on the uptake of new technologies. While it will draw on international experience, the alliance will also develop quantitative and qualitative patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) that are specific to China.

Simply translating terminology “does not work” for many of our populations, said Hao Hu, a research fellow at the China National Health Development Research Center. “We need context and culturally specific PROMS. And collecting this data from patients will be good,” he said, “for it will help doctors and patients communicate better.”

Simply translating terminology “does not work” for many of our populations, said Hao Hu, a research fellow at the China National Health Development Research Center. “We need context and culturally specific PROMS. And collecting this data from patients will be good,” he said, “for it will help doctors and patients communicate better.”

Work will start with developing disease specific PROMs for the most common disorders in China and much of these data will be collected via social media. An illustration of the ubiquitous use of the latter came when, as if as one, meeting participants took to their smartphones and formed an instant wechat community to foster joint learning. Out in the cold with Twitter, I could only watch as people punched their phones with enthusiasm. But it was warming to observe the commitment to getting patients’ views on where value in healthcare lies.

Tessa Richards, The BMJ. You can follow her on Twitter @tessajlrichards

Competing interests: I was paid to attend these meetings, and to speak from the perspective of a cancer patient at the HTA meeting and on The BMJ‘s patient partnership work at the launch of the China Health Outcomes Research Alliance.