A recent visit to Japan for the quadrennial meeting of IUPHAR, the International Union of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacology, prompted me to reflect on Japanese words that have entered the English medical vocabulary.

A recent visit to Japan for the quadrennial meeting of IUPHAR, the International Union of Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacology, prompted me to reflect on Japanese words that have entered the English medical vocabulary.

Japanese is rich in reduplications. The first definition of “reduplication” in the Oxford English Dictionary is “the action of doubling or folding”, which is just what duplication means. However, “reduplication” has a distinct grammatical meaning, not shared by “duplication”: “repetition of a syllable or letter, especially in the case of verbal forms”. Typically this occurs in the perfect tense of Greek and Latin verbs. For example, the paradigm of the Latin word to touch is tango, tangere, tetigi, tactum, with reduplication in the perfect tense, mimicking the repetition of a past action. Other examples include Sanskrit and Greek words for giving—dadāmi and δίδωμι, both meaning I give. Reduplication of this kind typically happens in verbs when the action is repeated—giving is supposed to be habitual. The Latin verb to give is dārē (in which both vowels are pronounced separately, as marked), which also reduplicates in the perfect tense as dedi, mimicking the repetition of a past action.

The onomatopoeic borborygmi, multiple rumbling of the guts, is another example of reduplication implying repetition. Reduplication can also indicate continuity, as in murmur and susurrus, or intensity, as in beri-beri (in Japanese kakke, literally “leg illness”), which is probably from the Sinhalese word beri, debility (i.e. much debility). O’nyong-nyong, a dengue-like disease, comes from East African words meaning severe joint pains.

Some Japanese reduplications have been imported into English.

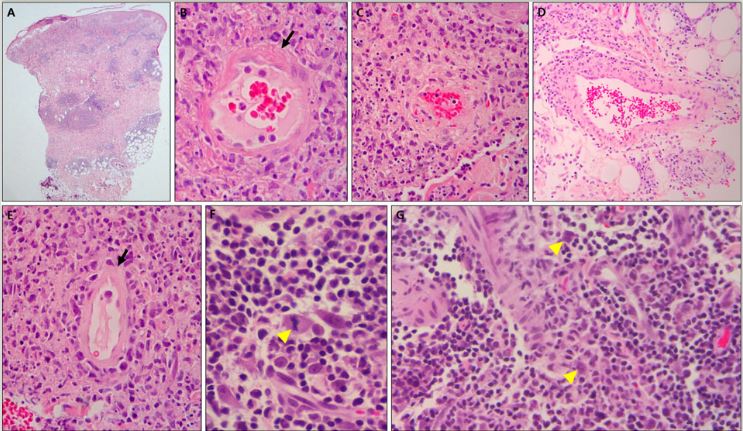

Tsutsugamushi fever, or scrub typhus, is from the Japanese words tsutsuga, illness, and mushi, an insect. I don’t know when this was first named in Japanese, but the earliest instance I have found in English is in the journal Science (1897; 6(139): 313-5), where it is described as “a malady, which is endemic in certain parts of [Japan], presenting the clinical feature resembling that of the typho-malarial fever”, since it is due to plasmodia of Orientia tsutsugamushi that invade red cells like the malaria parasite does (Figure 1). Identification of the parasite is attributed in the paper to Professor Kitasato’s Institute for Infectious Diseases in Tokyo, which gives its name to the Kitasato Archives of Experimental Medicine.

Figure 1. Tsutsugamushi parasites in skin (A,F,G) and blood vessels (B,C,D,E) (from Min Soo Jang et al. Ann Dermatol 2018; 30(1): 29-35)

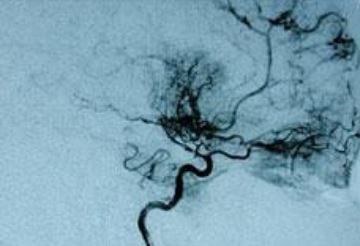

Moyamoya disease, a cause of stroke in young people, is occlusion of the internal carotid arteries or of arteries in the circle of Willis, causing a collateral circulation, responsible for the typical angiographic pattern, which resembles a puff of smoke (moyamoya in Japanese; Figure 2). The term has also been used to describe fuzzy echoes seen during echocardiography.

Figure 2. An angiogram showing the moyamoya phenomenon

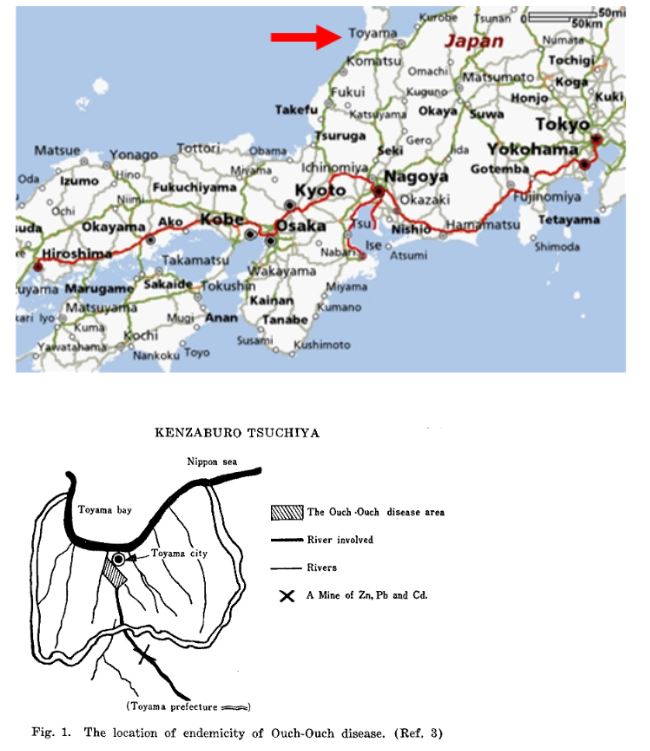

Itai-itai is painful osteomalacia secondary to cadmium-induced nephropathy. It was first reported in the downstream basin of Japan’s Jinzu River in the Toyama Prefecture in around 1912, but research into its cause did not begin until the 1950s. In 1955 Shogo Hosoya proposed an infectious cause, and in 1956 Noboru Hagino suggested that it was due to malnutrition. However, because the disease had been limited to the Jinzu River basin (Figure 3), further investigation led to the conclusion that it was due to chronic cadmium poisoning.

In 1961 the Toyama Prefecture set up a special council to find the cause, and in 1963 the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare set up a medical research council and the Ministry of Education a medical research team to jointly investigate further. In May 1968, the Ministry of Health and Welfare officially announced that itai-itai disease was due to chronic cadmium poisoning and that the cadmium came from “upstream discharge into the Jinzu River by commercial activities of the Kamioka Mining Co Ltd, at their Kamioka Mines.” This information comes from a 1998 annotation by the International Center for Environmental Technology Transfer. In Korea a similar disease is known as Onsan illness, from Onsan Bay, where pollution with cadmium, lead, copper, and zinc has been observed, affecting local residents, with similar pollution in the area of Ulsan further north. Deaths due to cadmium poisoning have been well described, for example in the Indian Medical Gazette in 1866.

Figure 3. Toyama Prefecture in Japan, the site of the first identification of itai-itai disease; the lower map is from a review by Kenzaburo Tsuchiya; reference 3 is a 1967 summary report on itai-itai disease by The Study Group of Itai-Itai Disease, supported by the Japanese Ministry of Education, 1963–1965, and the Study Group of Itai-Itai Disease, supported by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, 1963.

In Japanese “itai itai” means something like “ouch! ouch!”. Perhaps you say it twice because it doubles you up.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.