As the whole world knows, Doug Altman died this week.

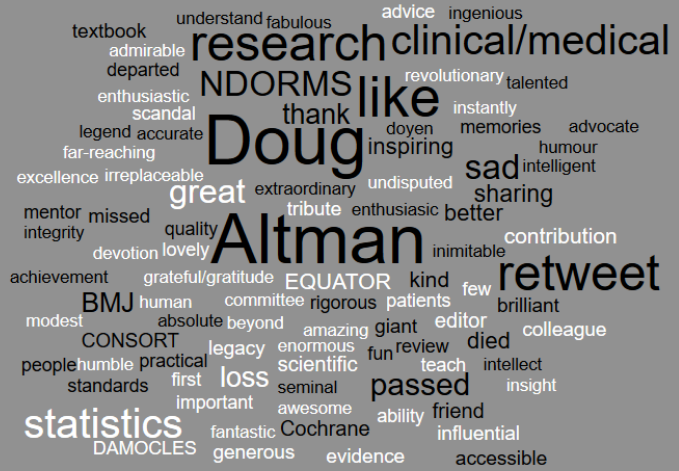

The news provoked a Twitter storm of large proportions, over 200 messages in five days, plus innumerable retweets. The significant words they contain are shown in the word cloud.

Figure: A word cloud showing the relative frequencies of the most relevant (value judgment) words distilled from the first 15 000 words in the tweets; I have combined cognate words (e.g. “stats”, “statistical”, and “statisticians” are all represented by “statistics”); nearly 400 instances of “Doug” and Altman” each outstripped even the number of instances of “and”

Some cited his classic editorial in The BMJ “The scandal of poor medical research”, with its pithy message: “We need less research, better research, and research done for the right reasons. Abandoning using the number of publications as a measure of ability would be a start.” I suspect that today he would add “and citation counts and spurious measures of impact”, especially since his citations are astronomical and his impact crushing. Others referred to his textbook Practical Statistics for Medical Research (1991) (“his red bible”); some reminded us of the acronyms CONSORT, DAMOCLES, EQUATOR; and others referred to the Statistics Notes in The BMJ, 68 of them (1994–2018), written with colleagues, often Martin Bland; more are in the pipeline.

Some cited his classic editorial in The BMJ “The scandal of poor medical research”, with its pithy message: “We need less research, better research, and research done for the right reasons. Abandoning using the number of publications as a measure of ability would be a start.” I suspect that today he would add “and citation counts and spurious measures of impact”, especially since his citations are astronomical and his impact crushing. Others referred to his textbook Practical Statistics for Medical Research (1991) (“his red bible”); some reminded us of the acronyms CONSORT, DAMOCLES, EQUATOR; and others referred to the Statistics Notes in The BMJ, 68 of them (1994–2018), written with colleagues, often Martin Bland; more are in the pipeline.

But the best description of all, in my view, was the suggestion that he had “geniousness”. Now this word is not to be found in any dictionary that I know of, although it deserves to be in them all. So what does it mean? Well it’s clearly a portmanteau word.

A portmanteau word is “a word formed by blending sounds from two or more distinct words and combining their meanings” (Oxford English Dictionary). Lewis Carroll introduced the idea in Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There (1871). Having discovered the poem “Jabberwocky” in the house in which she first finds herself after passing through the looking glass, Alice wonders what all the words mean and finally finds an interpreter in the form of Humpty Dumpty. “Slithy”, he tells her, means slimy and lithe and “mimsy” is miserable and flimsy. “You see,” he explains, “it’s like a portmanteau—there are two meanings packed up into one word.” Carroll explained this in his preface to The Hunting of the Snark (1876): “Humpty Dumpty’s theory, of two meanings packed into one word like a portmanteau, seems to me the right explanation for all. For instance, take the two words ‘fuming’ and ‘furious’. Make up your mind that you will say both words, but leave it unsettled which you will say first … if you have the rarest of gifts, a perfectly balanced mind, you will say ‘frumious’. Supposing that when Pistol uttered the well-known words—‘Under which king, Bezonian? Speak or die!’ [if] Justice Shallow had felt certain that it was either William or Richard, but had not been able to settle which, … he would have gasped out ‘Rilchiam!’”

Modern examples include chocoholic (chocolate + alcoholic), Frankenfoods (Frankenstein + foods), genetically modified foodstuffs, and Nintendinitis (Nintendo + tendinitis), damage from excessive playing of video games.

So “geniousness” clearly combines two nouns that apply perfectly to Doug Altman, genius and generousness. He was indeed a genius, in many ways, but particularly in the profundity of his understanding of the most difficult statistical concepts. I don’t recall how I came across the paper in which he and his colleagues provided “an explanatory list of 25 misinterpretations of P values, confidence intervals, and power”, published in the European Journal of Epidemiology (a journal that is not on my regular reading list), but having read it I discussed it with him when we met at an Evidence Live meeting in Oxford. His clear explanations made me want to read it again, and having done so this week I remain in awe. Doug’s genius also lay in his ability to see and solve problems, obvious when explained, that nobody else had noticed.

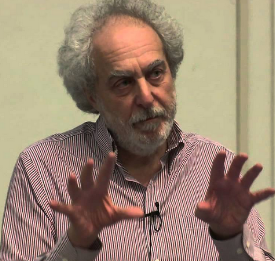

Figure: My favourite picture of Doug Altman, showing him in characteristic expository mode, lecturing definitively about reporting research at a Science in Transition symposium in Utrecht, 16 January 2014

Doug’s generousness is repeatedly mentioned by the twitterati: “fabulous, generous, brilliant, funny, inspirational, dearly loved”; “rigorous, generous, and fun”; “the most generous & modest global superstar”; “generous, stimulating and fun”; “humble, generous, funny & nurturing”; “generous and creative”; ”friend, generous colleague & agitator”; “a generous friend, great teacher, innovator and pioneer”; “supportive and generous”; “always generous to others”; “great, generous, with a massive legacy”. And that doesn’t say it all by any means.

“Geniousness” is a good way of summing it all up.

“Altman” is from the Yiddish Altermann, an old man, a name given to a child born after the death of a sibling or assumed by someone very ill, hoping to fool the Angel of Death into thinking that the person was too old to be worth claiming. Doug did not live to be old enough.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.