Kanye West’s revelation that he has bipolar disorder is a strike against stigma. Yet raising awareness is not enough

This is not a music review. I haven’t listened to Mr West’s latest album (or any of them) nor am I trying to bag tickets to Kanye’s next UK tour for one of my offspring by name dropping.

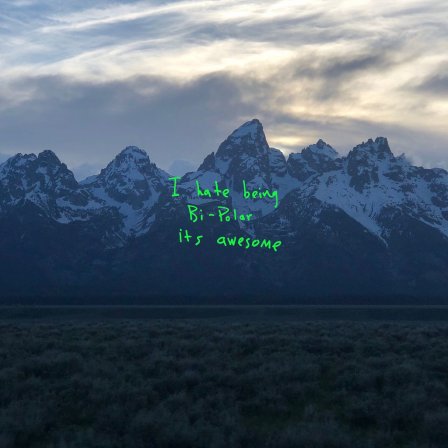

But the statement “I hate being Bi-Polar its awesome” scrawled in neon green handwriting across the cover of his latest album, and the conversation it generated on Twitter, certainly grabbed my attention.

But the statement “I hate being Bi-Polar its awesome” scrawled in neon green handwriting across the cover of his latest album, and the conversation it generated on Twitter, certainly grabbed my attention.

“I had never been diagnosed and I was like 39 years old,” he recently revealed in an interview, alluding to a diagnosis for bipolar disorder that he was now receiving support for following on from a year in which a long tour was abruptly cancelled, and West was hospitalised for suffering from exhaustion.

Much credit to him for sharing this. Among a sea of public figures who are more than happy to talk about milder mental conditions, severe conditions are still cloaked under a certain kind of unacceptableness—spoken of far more rarely.

“It’s not a disability but a superpower,” West says of his condition. Hearing positive, empowering language around mental illness is refreshing, making West’s revelation all the more powerful in minimising stigma.

But what absolutely cannot be minimised is that bipolar disorder is a serious mental illness.

West divides opinion to say the least, but I truly hope he will be instrumental in showing a worldwide audience that someone with bipolar disorder is far more than that label. The condition he speaks about, and other serious mental illnesses, can be completely debilitating without support.

As serious mental illnesses are often not well understood, the support can be dangerously lacking. Research by YouGov[1] found that just 42% of the UK public knew that it takes a psychiatrist to diagnose bipolar disorder. A lack of understanding and a lack of access to adequate support often come together in an unhappy pairing, blocking the early intervention that is so key to recovery.

In the UK, Stephen Fry’s accounts of his bipolar disorder and treatment over past years have laid important foundations to improving understanding of such conditions. The Royal influence via Princes Harry and William and the Duchess of Cambridge has also been significant. I’m hopeful that the shroud of shame around severe mental illness is finally beginning to lift.

Yet all the while, if awareness and understanding of severe mental illnesses continues to grow and people are encouraged to come forward to seek help, what is the use if we are then unable to support them, leave them waiting for months, or send them across the country for treatment?

In Kanye West’s own (third person, of course) words: “Think about people who have mental issues that are not Kanye West . . . think about somebody that does exactly what I did at TMZ but they just do it at work. Then Tuesday morning they come back and they lost their job.” Good point. So how can we help anyone, who isn’t Kanye West, with mental health problems ensure that they are able to continue with their life?

To meet the government’s target of providing treatment to one million people in England, 570 more psychiatrists are needed by 2021. This is a tall order and even this will leave a substantial number of people without access to specialist treatment.

This year there has been a huge rise of just over 30% in the number of doctors choosing to train in psychiatry. I’m certain that more open attitudes to mental illness and de-stigmatisation have played a large part in this.

“They are the people who will help patients of the future,” Stephen Fry said of this new intake of trainee psychiatrists. Indeed, this really is great news for patients who will benefit in years to come when these doctors are trained up. But what about people who need help today, and in the next few years?

Awareness alone of mental illness is not enough, and voters know it. Mental health services stood out as the NHS area that should receive more government funding, second only to A&E, in a recent Ipsos Mori poll.

Training skilled doctors takes 13 years, so getting the right people to treat severe mental illness now (or indeed anytime soon) means that we really do need to look far and wide. One out of two of all psychiatrists working in the NHS in England qualified outside of the UK.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists are pleased that the Home Office seem to have listened to calls to reconsider how visas are allocated to overseas doctors. In addition to this, further effort is needed to secure more child and adolescent psychiatrists. The numbers of consultant child and adolescent psychiatrists have dropped by over six per cent since February 2014, making it essential that child and adolescent psychiatrists are added to the national shortage occupation list so that it is easier to recruit specialist doctors from overseas.

If a global star was almost 40 before being diagnosed and supported for a severe mental illness, it’s too easy to see how everyone who isn’t Kanye West could go far longer without support.

We need to ensure that we have enough skilled doctors to stop this from continuing for yet another generation. The recruitment surge we have seen this year shows that at last we are on course to achieve this.

Wendy Burn is the president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Wendy Burn is the president of the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: None.

References

[1] YouGov research commissioned by the Royal College of Psychiatrists, August 2017. Total sample size was 2091 adults.