Language matters as a way of respecting women’s views and ensuring that they are empowered to make decisions

Natalie Mobbs, Catherine Williams, Andrew D Weeks

Avid readers of clinical guidelines will have noticed a change in emphasis in the NICE Intrapartum Care Guideline over the years. [1] While previous guidelines focused almost exclusively on clinical actions, the latest version emphasises the importance of good intrapartum communication and respect for women’s autonomy. Alongside advice on drug doses for oxytocics and optimal fetal monitoring techniques, a direction is now made to senior staff to “demonstrate, through their own words and behaviour, appropriate ways of relating to and talking about women and their birth companion(s), and of talking about birth and the choices to be made when giving birth.” The authors indicate that HOW the birth is conducted might be just as important as WHAT you do.

Although eyes may roll at the thought of “political correctness gone mad,” the change is well founded. Firstly, intrapartum care must keep in pace with and reflect changes in societal norms and expectations. While some may mourn the days when the doctor was in charge and their advice was gratefully received and unchallenged, there are now multiple, alternative sources of healthcare advice available to women both before and after consultations. With improved knowledge among women and a renewed recognition of respect for human rights in childbirth, comes an equalisation of status between doctor and woman. [2] To recognise this, the guideline envisages “a culture of respect for each woman” and the clinician should “ensure that the woman is in control of and involved in what is happening to her, and recognise that the way in which care is given is key to this.” [1] The role of birth attendant is no longer “owner” of the situation but “facilitator” of the health services.

The importance of women’s autonomy and good maternity communication has been brought to the fore by the Montgomery case, in which the obstetrician was criticised for not adequately communicating the risks of vaginal birth in a diabetic woman with fetal macrosomia. Although not explicitly stated, the judgment implies that the obstetrician’s duty was to alert the mother to the risks of both vaginal and caesarean birth, and provide a caesarean if preferred. Bolton states: “Doctors must be guides in providing care, and not leaders expecting obedience to their personal judgment of what is appropriate. Where there are options in care, the patient [sic] decides, not the doctor.” [3] The legally binding implications are wide-ranging and are a reminder that the woman makes her own decisions about care in pregnancy and birth, which obstetricians and midwives must respect, even when there are differences of opinion. Language use is key to effectively communicate options, recommendations, and respectfully accept the woman’s fully informed decision.

Secondly, improved psychological care of those in the healthcare system is closely linked to improved outcomes. Positive communication and interactions throughout the birthing process significantly affect the woman’s experience, which in turn can affect both her mental and physical health, as well as her relationship with her baby postnatally. [4, 5] In disease and illness, good communication between physician and patient has been shown to “exert a positive influence not only on the emotional health of the patient but also on symptom resolution, functional and physiological status, and pain control.” [6, 7, 8] In maternity care the proof of this is evidenced by markedly improved outcomes simply with provision of a labour companion: a systematic review shows that it reduces caesarean rates, operative vaginal births, use of analgesia, and negative feelings regarding the birth experience. [9] Not due to any clinical intervention, but simply due to the provision of support.

Sadly, some women may not be aware of their human rights during childbirth: rights for respectful care, privacy, and freedom of choice concerning their birth. [8] It is therefore the duty of caregivers to use language that will help empower all women. Campaigning organisations AIMs, and NCT, joined more recently by Birthrights, and the #MatExp movement, have long advocated that improvements to maternity care and good communication are intrinsically linked. [10] Language signals the nature of the relationship between woman and caregiver, and can deny or respect a woman’s autonomy. This challenge resonates worldwide, and is now being addressed by recent WHO research. [11]

In practical terms, this means that those providing maternity care need to consider their use of language seriously. Not only as a way of respecting women’s views and ensuring that they are empowered to make decisions, but also in order to respect their human rights. This requires careful use of language, reflection on our own practice as caregivers, listening to women, and communicating appropriately, plainly, and respectfully to guide her through the complexities of maternity care.

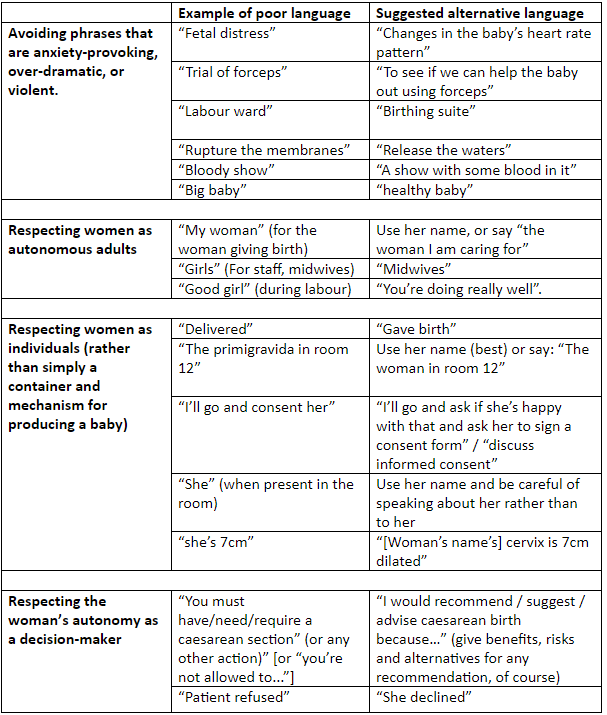

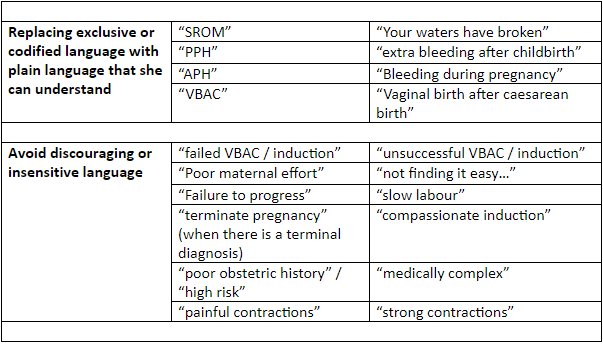

Over a three month period, language use in maternity settings was explored with the multidisciplinary, collaborative #MatExp Facebook group to identify how language could improve the experiences of women, babies and families. A preliminary table with four categories was created and shared with the #MatExp Facebook group for comment. Within a week 121 comments were received offering further input regarding commonly used phrases and expressions used in maternity care, which should be challenged. The original table was altered and six key categories were identified that required change: paternalistic or patronising language; language which objectifies women; anxiety-provoking language; dictatorial language; discouraging language and exclusive or codified language. Examples of poor language are shown in table 1, with suggested alternatives.

Table 1: Good practice in birth communication.

Good communication during the birthing process is critical to good maternity care; but achieving a shift in deeply ingrained language, and the thinking it reflects, is difficult. There is a fine line between changing terminology to integrate language which is more respectful, inclusive, and less intimidating for the mother, and substituting vague, verbose language which hinders the original message. It is pointless to change the term “crash section” to “a caesarean section that we will recommend to the woman is done as rapidly as possible” if this alteration prevents rapid understanding of the gravity of the situation among medical practitioners. Language must still be adjusted according to whom we communicate with and why.

The use of insensitive language can be indicative of an underlying malaise, which reveals underlying attitudes and prejudices. It is essential that we achieve respectful practice, ensuring that women have complete understanding and control of their own care. If we can achieve that, then the use of appropriate language will follow on naturally.

Natalie Mobbs is a fourth year medical student at the University of Liverpool.

Natalie Mobbs is a fourth year medical student at the University of Liverpool.

Catherine Williams is a service user representative and advocate, involved in developing and improving local maternity services since 2004. She is a committee member of National Maternity Voices (MVP chairs and service user reps), she also serves on a number of research steering groups, and holds a NICE Fellowship.

Catherine Williams is a service user representative and advocate, involved in developing and improving local maternity services since 2004. She is a committee member of National Maternity Voices (MVP chairs and service user reps), she also serves on a number of research steering groups, and holds a NICE Fellowship.

Andrew Weeks is professor of international maternal health care at the University of Liverpool. He is director of both the Sanyu Research Unit and the WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Research Synthesis.

Andrew Weeks is professor of international maternal health care at the University of Liverpool. He is director of both the Sanyu Research Unit and the WHO Collaborating Centre for Research and Research Synthesis.

Acknowledgements: We thank the contributors to the #MatExp Facebook group for their suggestions and comments. Consent was received from the contributors to use the comments in this article.

Competing Interests: We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: None (CW served as a lay member on NICE CG190 Intrapartum Care for healthy women and babies 2014 and is a NICE Fellow 2016-19).

References:

1 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Intrapartum care for healthy women and babies. Clinical guideline CG190. 2014 Dec [updated 2017 Feb; cited 2017 Sept 6]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg190/chapter/Recommendations#care-throughout-labour

2 Birthrights; Protecting Human rights in Childbirth. Your Rights. Internet. 2017 [cited 2017 Oct 5]. Available from: http://www.birthrights.org.uk/resources/your-rights/

3 Bolton H. The Montgomery ruling extends patient autonomy. BJOG. 2015 Aug;122(9):1273.

4 Harris R, Ayers S. What makes labour and birth traumatic? A survey of intrapartum ‘hotspots’. Psychol Health. 2012;27(10):1166-77.

5 Reed R, Sharman R, Inglis C. Women’s descriptions of childbirth trauma relating to care provider actions and interactions. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2017 Jan 10;17:21.

6 Stewart MA. Effective Physician-Patient Communication and Health Outcomes: A Review. CMAJ 1995 May 1;152(9):1423-1433.

7 Redelmeier DA, Molin JP, Tibshirani RJ. A randomised trial of compassionate care for the homeless in an emergency department. Lancet. 1995;345(8958):1131-4.

8 Kelley JM, Kraft-Todd G, Schapira L, Kossowsky J, Riess H. The influence of the patient-clinician relationship on healthcare outcomes: a systematic review and metaanalysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94207.

9 Bohren MA, Hofmeyr GJ, Sakala C, Fukuzawa RK, Cuthbert A. Continuous support for women during childbirth. CDSR. 2017 July 16;(7).

10 Maternity Experience. Identifying and sharing best practice across the nation’s maternity services. 2017 [cited 2017 Oct 5]. Available from: http://matexp.org.uk

11 Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza JP, et al. (2015) The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. PLoS Med 12(6): e1001847.