We collected hundreds of drawings—snapshots of an often overlooked corner of the world through the eyes of sick children

All eyes stared at me when I dragged the plastic table into the middle of the waiting room. Tired and curious eyes. Tracking my every move. Some of the children were lying on narrow wooden benches with their arms tucked tightly into their shirts, trying to keep warm in those cold early hours of the day. Others were snuggled in their mothers’ laps, neatly wrapped in colorful cloth. All were waiting to be tested for malaria, one of the leading causes of death for children under 5 in sub-Saharan Africa.

All eyes stared at me when I dragged the plastic table into the middle of the waiting room. Tired and curious eyes. Tracking my every move. Some of the children were lying on narrow wooden benches with their arms tucked tightly into their shirts, trying to keep warm in those cold early hours of the day. Others were snuggled in their mothers’ laps, neatly wrapped in colorful cloth. All were waiting to be tested for malaria, one of the leading causes of death for children under 5 in sub-Saharan Africa.

According to the World Health Organization, in 2015 303 000 children under the age of 5 died from malaria—that’s more than one child every two minutes—and 96% of these deaths were in the African region.

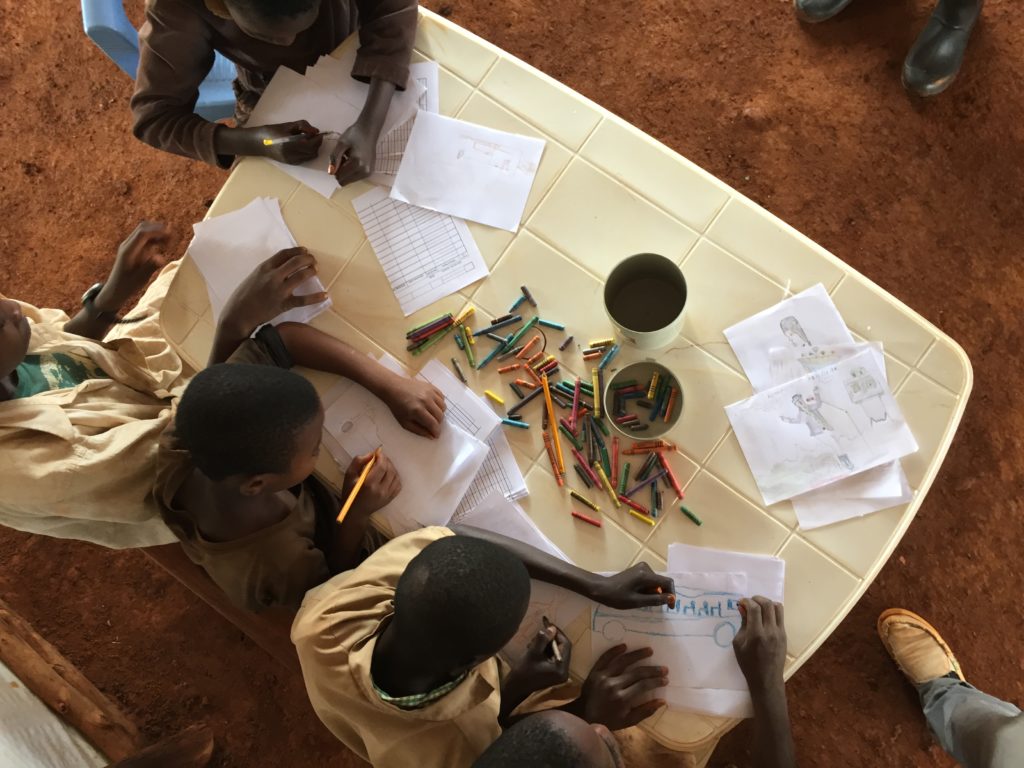

I found something to wipe the thick dust off the table, brought over an empty plastic container from the pharmacy, and filled it with crayons. Taking some scrap pieces of paper out of my bag and spreading them over the table, I looked up to see a few of the children now sitting up on the benches, curiously scanning what I had just laid out.

One young girl, about 4 or 5 years old, wearing a muddy T-shirt long enough to serve as a dress walked over to the table and cautiously leaned against it. I picked out a crayon, drew a smiley face on a paper scrap, and showed it to her. Then I rushed off to finish my morning rounds.

In the far western side of the country, Tanzania hosts more than 361 000 refugees, the majority of them from neighboring Burundi. In my last assignment with Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), I was the nurse manager in the Nyarugusu camp for two malaria clinics that were aimed at limiting illness and death from malaria—one of the biggest health risks in the camps.

Children are particularly vulnerable, especially during the rainy season, when stagnant water provides a breeding ground for mosquitoes. In January 2017 alone MSF treated 6802 people for malaria in Nyarugusu. With so many people suffering from malaria in the rainy season, that often means long waiting times.

Waiting is an inescapable part of refugees’ daily lives. From the moment they set foot in the camp, the waiting begins: waiting for registration upon arrival, waiting for health screening, waiting for water, waiting for food, waiting to wash after waiting for soap, waiting for additional latrines to be built. As a refugee, patience is essential for survival.

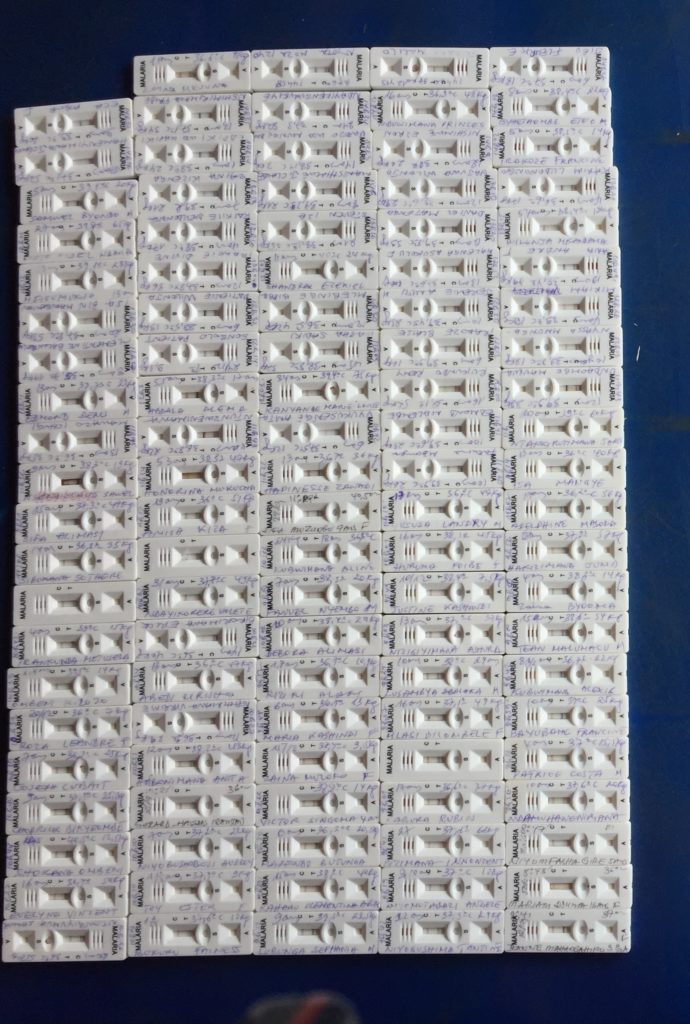

My team and I worked very hard to make sure that our malaria clinics operated as efficiently as possible—adjusting staffing and patient flow to cut waiting times by half. But in a busy malaria clinic in the middle of the rainy season, some waiting is unavoidable: first the wait to be tested, then the dreadful 20 minute wait for test results, followed by the wait to be treated, and finally the wait outside the pharmacy to get medication. But waiting need not be boring.

When I decided to put the box of crayons I found to use, I didn’t think much of it. But when I came back to the waiting room towards the end of that first day, the table was covered with drawings. Some were of recognisable objects, some just marks; some were finished, others not—perhaps abandoned by the artists when their test results were called out.

By the end of the week, children of all ages were struggling to get onto the table. The crayons were worn down and the paper scraps were nearly used up. I asked a friend to bring more crayons from Dar Es Salaam, a city in Tanzania, and gathered spare paper from anywhere I could find it. The next week the drawing continued. I asked the clinic health promoter to tell the children they could take their drawings home with them. Some did, but the majority left their masterpieces behind. It’s not easy to keep a piece of paper clean and dry when living as a refugee.

So the waiting room became an art gallery. At the end of each day, I collected the drawings and began to put them up on the walls of the waiting area—a task easier said than done. Tape on walls made from plastic sheets does not hold well in the heat and humidity of the camp. But it worked well enough, and soon my colleagues and I became accidental curators.

Going through them every few weeks, we noticed recurring themes. Brick houses and tents, soccer balls and footballers, flowers, fruit (mainly pineapples), fish, drawings of men and women in fancy attire—suits, dresses, and sunglasses. There were also drawings of the buses that brought some of the refugees to the camp, as well as of helicopters, military men, and machine guns. By the end of my assignment with MSF, we had collected hundreds of drawings—snapshots of an often overlooked corner of the world through the eyes of sick children.

For me the drawings were a special connection to the children of the camp, most of whom don’t speak French or English. I was able to have a conversation with hundreds of them without saying a word. I saw their hopes and dreams, their fears and scars, their friends and families. And many drawings of pineapples. For them it was a way to pass the time, to escape for a moment, to create, and maybe have a little fun while waiting.

Today those children are likely still waiting—for another checkup, another tent, another soap distribution—and hopefully still drawing.

Farrah Kashfipour is a critical care nurse. Last year she worked in the Nyarugusu and Nduta camps in Tanzania as a nursing activity manager, interim pharmacy manager, and nurse trainer with Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). MSF has since phased out its medical activities in Nyarugusu camp, but remains the main medical provider in Nduta camp where the organisation runs a 175 bed hospital and six health posts.

Competing interests: None declared.

Please support The BMJ‘s Christmas 2017 appeal for Médecins Sans Frontières, bringing medical volunteers to the world’s neediest people: donate at www.msf.org.uk/bmj

£123 could pay for a blood transfusion for three people

£65 could buy a stretcher to help move an injured person to safety

£54 could provide antibiotics to treat 40 war wounded people

Donate online: www.msf.org.uk/bmj

Donate by phone: 0800 408 3897 (UK only)