We want innovation to improve our patients’ lives and protect their safety

For a commuter with a chesty cough on the platform of London’s Marylebone station last Monday morning, the promise of free access to instantaneous healthcare on their smartphone would have been a welcome solution to the problem of fitting a prompt general practice appointment into a busy working life.

For a commuter with a chesty cough on the platform of London’s Marylebone station last Monday morning, the promise of free access to instantaneous healthcare on their smartphone would have been a welcome solution to the problem of fitting a prompt general practice appointment into a busy working life.

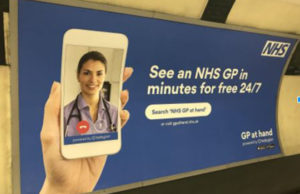

The partnership between Babylon, a digital health company, and GP at Hand, an NHS GP practice, raises some key questions. Advertisements across London (and on Instagram and Facebook) invited people to register as NHS patients at the GP at Hand practice, creating the possibility of it becoming a “super practice” and Babylon attracting high volumes of data transactions from NHS patients.

Notwithstanding policy talk about “disruptive” technological innovation, the billboards across London were not announcing a great leap forward in artificial intelligence. This step appears to have been a targeted marketing strategy to attract less complex patients (along with their capitation fee and NHS data) away from traditional general practices and into Babylon’s partner practice, GP at Hand.

Much of the cautious reaction, including from the Royal College of General Practitioners, centred around GP at Hand’s ostensible attempt to preferentially register patients with less complex problems and the prediction that this would create a two-tier system. One of us (LC), an NHS patient with multiple sclerosis, hypothyroidism, and hypercholesterolemia, is concerned what that means for her. She notes:

“I welcome disruptive innovation, but not like this. How can it be patient centered when it excludes patients like me? I would benefit from video consultations, especially when my multiple sclerosis is playing up and I would rather not venture into a disease-ridden waiting room. If such a two-tiered system is introduced widely, my fear is that people like me will wait longer to see an over-stretched, stressed GP in a system that is unsupportive of the sick.”

Whilst not rejecting registration by any particular patient group, GP at Hand suggest, at the NHS’s request, that the following patients would be “less appropriate” for this service; those with serious chronic illnesses, the frail and elderly, pregnant women, patients with learning disabilities, and people with major mental health needs. Under current contractual arrangements, a practice that skews its list away from patients with chronic ill health is likely to improve its financial position compared with one that takes all comers and commits to providing comprehensive care for the local community. A patient registering with GP at Hand takes their capitation fee with them. Their former practice may be left with fewer resources to deal with an increasingly concentrated population of sick patients. New models could conceivably create efficiency savings in the care of relatively simple patients but would require a comprehensive rethink of the way we structure and resource the care of these patients as well as those with the greatest need. GP at Hand is also offering their NHS patients in-app purchases of private services which raises an important question about the extent to which paid-for services are surfaced more prominently in NHS workflow.

We want innovation to improve our patients’ lives and we want to protect their safety. Some have challenged Babylon’s claim that the “chatbot” algorithms which they seek to introduce for patient triage are better than a doctor at triaging patients, on the basis of a limited suite of internally-conducted laboratory-style studies. Iterative development of these algorithms is – we assume – ongoing, and this highlights a broader issue: current regulatory approval mechanisms for medical devices are ill-suited to digital technologies, which present a multitude of potential value propositions, are complex in their inputs and outputs, and perpetually evolve.

Companies are increasingly gaining access to strategic assets within the NHS architecture (such as NHS 111, general practice services, and Biobank). Once in place and as their algorithms develop more sophisticated proprietary features, they could offer huge potential benefits, but may also become so deeply embedded that the NHS cannot work without them. The contractual arrangements that make such penetration possible should surely (if they occur at all) happen strategically and in plain sight. Arguably, we should also be developing these algorithms (like the Human Genome Project or NICE guidelines) as a public good, or perhaps eventually as “algorithmic generics”, in addition to developing them as the intellectual property of private companies.

Much of the potential monetary value of digital health companies is in the development of proprietary algorithms and the datasets they are trained on. These datasets may come from the data that millions of NHS patients willingly place on their own medical records and/or on their smartphone, since the smartphone app is the means by which the patient accesses NHS care and apps could potentially collect and transmit phone meta-data if the user enables this function. Our patients, their data, and NHS institutions that hold them have a huge financial value in the global market. As speculators compete in the digital gold rush, we may wish to find a way to return some financial benefits to the patients and public institutions whose data were used to generate them.

Democratizing healthcare is a noble goal. Destabilising an equitable care system is not. The long-heralded arrival of digital health, like the biomedical revolution before it, has the potential to increase the quality and quantity of patients’ lives. We should continue to strive for a system which balances the promotion of innovation with the protection of both individuals and the population from harm.

Alexander E Finlayson, Doll Fellow at Green Templeton College, Oxford University and Salaried GP.

Eleanor Barry, NIHR Doctoral Research Fellow, University of Oxford.

Lynne Craven, NHS patient.

Trisha Greenhalgh, professor of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford.

Competing interests: We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: AF is a salaried GP and Fellow of Green Templeton College, Oxford University. He is the Director of MedicineAfrica an Educational Technology social enterprise funded by DFID to do capacity building work in Somalia. He is also the founder and currently unpaid director of TheHill, an NHS Digital Health Lab and Incubator in Oxford which has received funding from the MRC, NHS, and EU. He was commissioned to develop a technology transformation strategy for Primary Care in Oxford City. He consulted for Telenor Digital in Bangladesh. He is interested in developing technology which is good both for individuals and for systems. Other authors declare no competing interests.