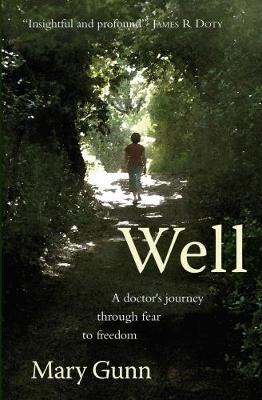

Mary Gunn, looking very well and wearing her 65 years lightly, stands in front of the audience in an Edinburgh bookshop describing how eight years ago she was diagnosed with recurrent breast cancer and given two years to live. She is launching her book Well: A Doctor’s Journey Through Fear to Freedom.

Mary Gunn, looking very well and wearing her 65 years lightly, stands in front of the audience in an Edinburgh bookshop describing how eight years ago she was diagnosed with recurrent breast cancer and given two years to live. She is launching her book Well: A Doctor’s Journey Through Fear to Freedom.

The book tells the story of Mary’s illness and also something of her life, but the main point of the book is to share what she learnt in learning to live with her illness, her fear, and her possibly imminent death. It’s not a self-help book in the typical mould, but it will surely be helpful to anybody with a serious illness or, indeed, anybody affected by chronic fear. Mary roamed widely, way beyond conventional healthcare, in her search for acceptance. I was greatly impressed too by how much Mary, who as a young doctor worked in rural Malawi and then later as a general practitioner in the Scottish Borders, learnt from her patients. She learnt more from them than from her textbooks or medical journals, which is probably true of all good doctors.

Three foreigners provide key moments in Mary’s book. The first is an unnamed Malawian woman with HIV/AIDS who said to her doctor: “When you get AIDS there are two illnesses. The first illness is the problems and pains you suffer with HIV. You have to deal with that. The second illness is the fear of what HIV will do to you in the future. It is very important not to catch the second illness.”

The story of Mary’s first illness can be told briefly, although it seems remarkable to someone like me who was a junior doctor in the 70s that somebody could be not only alive but also so well eight years after a diagnosis of recurrent breast cancer. (Mary, I should make clear, was the first medical student I met on my first day at Edinburgh Medical School in 1970, and we are friends today.)

Mary first had breast cancer diagnosed in 1997 when she was 44, and she knew from the moment she felt a hard lump in her breast that it was “cancer until proved otherwise.” It proved to be grade three cancer and if, like Mary when told the news, you can’t remember how many grades there are—there are three. She had hoped there were 10. She had a mastectomy, which showed that two of five lymph nodes in her left axilla contained cancer cells. The cancer was also very close to her chest wall. Postoperatively, Mary had radiotherapy, but at that time there was not strong evidence of further benefit from chemotherapy. Mary initially decided against chemotherapy, wanting to get back to work as soon as possible, but then looked at the slim evidence available and decided to have chemo as well.

Telling her young children was the most difficult part of her illness, and she wrote them a moving letter, which she reproduces in part in the book, in case she should die. She found it years later in her underwear drawer.

She remained well until January 2010 when she noticed a small swelling on her left chest. Rapid investigations showed a recurrent cancer the size of a grapefruit immediately behind her sternum. The options for treatment were surgery, radiotherapy, or hormonal treatment. The surgery with the cancer so close to vital organs would be “heroic but non-curative” and would mean replacing her sternum with a titanium plate. Radiotherapy was also unattractive because a large dose would be needed and would leave Mary exhausted. She opted for anti-oestrogen treatment, but she also contacted by Skype a famous homeopathic doctor in Mumbai whom she knew and respected.

Rajan Sankaran is the second foreigner who is central to Mary’s book. He gave her an appointment within three days and spent two hours covering “how I was feeling, what the scan had shown, past illnesses, my childhood, my likes, my dislikes, my hopes, my fears, the things that most concerned me and what I was sensitive to. Nothing about me as a person was left out.” He also prescribed homeopathic remedies. Mary started her medical career with the usual scepticism of doctors towards homeopathy, but her experiences with patients treated with homeopathy changed her view. The chapter in which she discusses the usefulness of homeopathy is entirely rational.

Most of Mary’s book is about dealing with “the second illness,” the fear that can overwhelm and paralyse. “Fight or flight” are the usual responses. The flight may be internal rather than external using “Netflix, retail therapy, sunny holidays, drugs, alcohol.” “I’ve tried them all,” writes Mary. The alternative is to “go to war with something or someone.” Neither is effective, and Mary advocates “a third option, one that is counterintuitive: to drop the avoidance and simply turn in and face our own inner fear.”

Mary was helped to do this by the third foreigner in her story, Lama Yeshe, abbot of Samye Ling Buddhist monastery in Eskdalemuir in the Borders of Scotland. Mary went to see him when she was first diagnosed with cancer. He reacted differently from everybody else, being unmoved, and emphasising the normality of being ill. “I think that when you are ill, you in the West suffer more than we do. In Tibet, as soon as we are born we know that suffering, illness, and death are part of life. To some they come early . . . to some late.”

Lama Yeshe was most helpful to Mary when her cancer returned. She went to see him in a state of terror, thinking that she was likely to die soon. “Lama Yeshe, I feel as if I have a hand grenade inside my chest . . . it’s terrifying.” To her surprise he responded by describing the major problems he too had in his own ageing body and then “Gesturing to our two, definitely no-longer perfect, bodies, he burst out laughing—his shoulders shook with it—and said, ‘Very bad time now to identify with body: body falling apart.'”

It’s impossible to imagine a doctor responding in this way (he or she might be struck off for such a response), but it was a liberating moment and a turning point for Mary. She understood that she had been identifying too much with her body, failing to recognise that she is much more than her body.

Part two of Mary’s book discusses the many “openings, teachings, and practices” that can help transform fear, teachings she practises herself. The final part of the book invites anybody severely affected by fear of whatever cause to experiment with the options. There is no one route, and Mary does not offer a prescription.

Looking at Mary at her book launch, I wondered how much her orthodox treatment, her homeopathy, her learning from Lama Yeshe and others, her experimentation, her family, chance, and her own internal resources allowed her to look and be so well eight years after being diagnosed with recurrent breast cancer. Learning to overcome “the second illness” has surely been central.

Well: A Doctor’s Journey Through Fear To Freedom by Mary Gunn is published by Saraband.

Richard Smith was the editor of The BMJ until 2004.

Richard Smith was the editor of The BMJ until 2004.

Competing interest: RS has known Mary Gunn for 47 years and made some comments, which might conceivably have been helpful, on drafts of her book before publication.