In 2012, Savita Halappanavar died in an Irish hospital from miscarriage complications after being refused an abortion. The treating physicians believed that because the fetus still had a beating heart their “hands were tied.” Under Irish law, abortion is a criminal offence unless necessary to save the life of the pregnant woman, yet there is little clarity on this exception. Following nationwide protests, the government introduced the Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act 2013 to clarify the law and to regulate access under it. Years earlier, the European Court of Human Rights called for precisely such regulation moved by the impossible position of physicians who “faced criminal charges, on the one hand, and an absence of clear legal, ethical, or medical guidelines, on the other.”

In 2012, Savita Halappanavar died in an Irish hospital from miscarriage complications after being refused an abortion. The treating physicians believed that because the fetus still had a beating heart their “hands were tied.” Under Irish law, abortion is a criminal offence unless necessary to save the life of the pregnant woman, yet there is little clarity on this exception. Following nationwide protests, the government introduced the Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act 2013 to clarify the law and to regulate access under it. Years earlier, the European Court of Human Rights called for precisely such regulation moved by the impossible position of physicians who “faced criminal charges, on the one hand, and an absence of clear legal, ethical, or medical guidelines, on the other.”

The circumstances in Ireland are tragic, but not uncommon. Abortion laws are often written in vague terms, breeding uncertainty and even conflict as to what the law allows in an individual case. This creates a “chilling effect” on service providers and women, both cautious against an uncertain risk of criminal prosecution. A UN human rights report named the lack of access to information, specifically on when and how abortions may be lawfully obtained or provided, as a key public health harm of criminalization.

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs have thus launched the Global Abortion Policies Database, an open-access repository of abortion laws, policies, standards, and guidelines for 197 countries. Designed to strengthen efforts to eliminate unsafe abortion, the database acknowledges and engages law and policy as a social determinant of safe abortion. The association between restrictive laws and unsafe abortion is well documented, especially among marginalized social groups. Beyond prohibiting abortion and forcing women to seek services across borders or in clandestine settings, restrictive abortion laws also decrease the availability of, deter and delay access to lawful care through burdensome authorization procedures, unnecessary service delivery requirements, and increased costs.

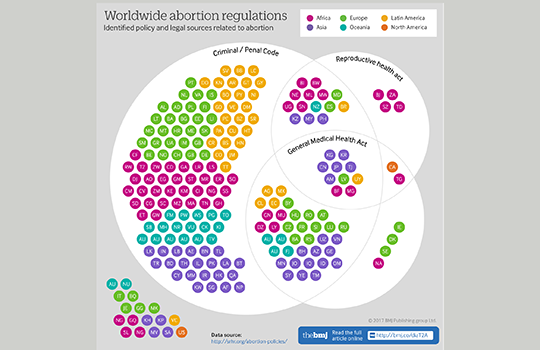

The breadth of abortion law captured in the database is one of its key innovations. Global abortion maps and other collections tend to focus on the legal grounds for abortion, classifying countries on this basis. The database provides a more comprehensive picture, capturing a range of “policy domains” (legal grounds, gestational limits, authorization and service delivery requirements), as well as, the complexities and subtleties of regulation in multiple and sometimes conflicting standards or sub-national variation. Moreover, while abortion was historically addressed in penal codes, these have been increasingly replaced or supplemented by health legislation, constitutional court decisions, and other forms of soft regulation such as clinical guidelines and medical ethics codes. The database captures these many sources of regulation, and thereby dispels the myth of a single “abortion law.”

Through this comprehensive picture, the database endeavors to make accessible clear and accurate information on abortion law and policy, and thereby suggests that knowledge is perhaps the more critical determinant of safe abortion. Women’s limited or inaccurate knowledge of abortion law influences how they seek services, including in countries with liberal laws. [1][2][3] Service providers’ legal knowledge also influences how and whether they provide care, with studies showing a correlation between accurate knowledge and progressive attitudes. [4][5][6] The same holds true for policy-makers, who often do not know what the law allows or what obligations it entails for them. [7][8]

Beyond the European Court, other international courts and commissions, as well as, constitutional and supreme courts have recognized legal obligations on government to create regulatory frameworks for lawful abortion, including clear criteria and procedural protections. [9][10] To support governments in meeting these obligations, the database links country profiles with human rights standards on abortion law and policy. Moreover by providing accurate and accessible information on these standards, the database supports community actors to hold governments accountable for gaps between these entitlements and abortion practice on the ground. Last by facilitating comparison across countries and geographical regions, the database raises the standard for government justification. It is harder to defend a restrictive law or policy in the face of available legal alternatives, much less against evidence-based WHO technical and policy guidance, which the database conveniently provides to supplement country-level data.

Yet formal law and policy is not always the path to justice. One of the most striking lessons of the database is the silence of law, the domains it leaves undecided. There is a danger to more law, more standards, and more procedures in the name of clarity and security. Many criticize the new Irish law because its narrowly formulated ground and procedures to strictly confine its interpretation entrench a fundamentally unjust law. The history of abortion decriminalization is marked, rather, by physicians who have worked the gaps and ambiguities of law in the name evidence-based medicine and in the protection of women’s health and human rights.

Joanna Erdman is the MacBain Chair in Health and Policy Law at the Schulich School of Law, Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada.

Declaration of interests: None

References:

[1] NI. Abeyasinghe et al., “Awareness and Views of the Law on Termination of Pregnancy and Reasons for Resorting to an Abortion among a Group of Women Attending a Clinic in Colombo, Sri Lanka” (2009) 16 J Forensic & Leg Medicine 134-137.

[2] HM. Marlow et al., “Women’s Perceptions about Abortion in their Communities: Perspectives from Western Kenya” (2014) 22:43 Reproductive Health Matters 149-158. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(14)43758-3

[3] CH. Rocca et al., “Unsafe Abortion After Legislation in Nepal: A Cross-sectional Study of Women Presenting to Hospitals” (2013) 120:9 BJOG 1075-1084. doi:10.111/1471-0528.12242

[4] C. de Costa, H. Douglas & K. Black, “Making it Legal: Abortion Providers’ Knowledge and use of Abortion Law in New South Wales and Queensland” (2013) 52 Australian and New Zealand J of Obstetrics and Gynecology 184-189.

[5] CM. Payne et al., “Why Women are Dying from Unsafe Abortion: Narratives of Ghanaian Abortion Providers” (2013) 17:2 Afr J Reproductive Health 118-128.

[6] Silvina Ramos, Mariana Romero & Agustina Ramón Michel, “Health care providers’ opinions on abortion: a study for the implementation of the legal abortion public policy in the Province of Santa Fe, Argentina” (2014) 11:72 Reproductive Health 1-10.

[7] AM. Moore, R. Kibombo & D. Cats-Baril, “Ugandan Opinion-leaders’ Knowledge and Perceptions of Unsafe Abortion” (2014) 29 Health Policy & Planning 893-901. doi:10.1093/heapol/czt070

[8] FE. Okonofua et al., “Perceptions of Policymakers in Nigeria Toward Unsafe Abortion and Maternal Mortality” (2009) 35:4 Intl Perspectives on Sexual & Reproductive Health 194-202.

[9] RJ Cook, JN Erdman & DM Dickens, “Achieving transparency in implementing abortion laws” (2007) 99:2 Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 157-61.

[10] JN Erdman, “The Procedural Turn: Abortion at the European Court of Human Rights,” in R.J. Cook, J.N. Erdman and B.M. Dickens eds., Abortion Law in Transnational Perspective: Cases and Controversies, 121-142 (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014).