Last week I discussed the nonlinear nature of systematic reviews and suggested that many aspects of medical science are also nonlinear. I believe this to be true of translational medicine.

Last week I discussed the nonlinear nature of systematic reviews and suggested that many aspects of medical science are also nonlinear. I believe this to be true of translational medicine.

The word “translation” derives from the Latin “translatio”, which in turn is derived from the supine form, translatum, of the irregular verb transferre, whose primary meaning is to carry or cause to be carried from one place to another. “Translatio” therefore meant the action of physically moving something or someone from one place to another, transplantation or change of position, the transfer of possessions or rights from one person to another, and, figuratively, the movement of ideas from one context to another or of words from one language to another. Although translation is often thought of as occurring in one direction only, these meanings imply two way processes, or bridges that can be crossed in both directions. This commutativity has been discussed many times in relation to translational research in different ways, typically by reference to a “two way street”.

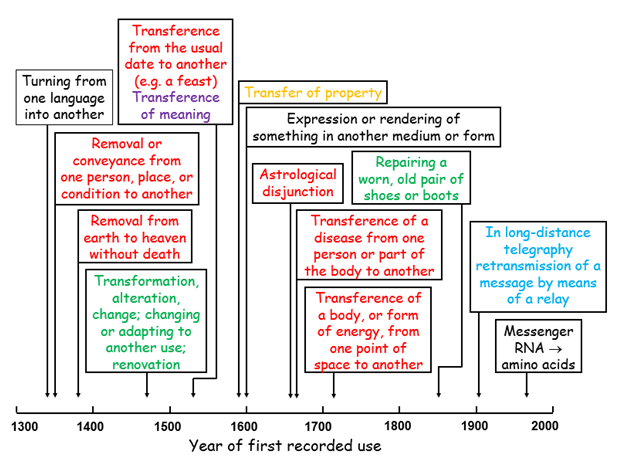

The definitions of “translation” given in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) are shown below. The most familiar, “Turning from one language into another”, is the earliest recorded (14th century). The latest definition refers to the production of amino acids under instruction from messenger RNA. The meaning that we nowadays also attach to it in a scientific context (e.g. in the term “translational research”) is not listed. That may be partly because there is no satisfactory definition.

Definitions of “translation” listed in the Oxford English Dictionary, generally defined as “the action of translating (or its result)”; the different colours reflect the different subsections in the dictionary entry into which the definitions are gathered

The idea of translational research as a formal process has its roots in the idea of “diffusion of innovations”, as defined by Everett Rogers in his 1962 book of that title: “the process in which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system” (although diffusion is only one aspect of translation). The Stevenson–Wydler Technology Innovation Act of 1980, the first major US technology transfer law, required federal laboratories to participate in and budget for technological advances, and was followed by the Federal Technology Transfer Act of 1986, which established the Federal Laboratory Consortium and enabled federal laboratories to enter into Cooperative Research and Development Agreements (CRADAs) and to negotiate licences for patented inventions.

A paper in 1980 referred to “the translation of research to nursing practice”, and another in the same year to “translation of the advances in the field of diabetes research with least delay into improved care for the diabetic in the setting of model patient care demonstration units within the centers and through outreach programs through the regional community”. A 1986 paper referred to “the role of the clinical environment in the translation of research into practice”. These rare examples heralded increasing awareness of the importance of translational research.

In 1988 Greer described how diffusion applied to the ways in which new medical technologies were introduced into clinical practice, differentiating “formed” (i.e. complete) and “dynamic” (i.e. still developing) technologies, and explaining the disjunction between clinical practice and the evidence that should underpin it. Then, in 1989, the Diabetes Division of the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), changed its name to the Division of Diabetes Translation, the stated aims of which were to “reduce the preventable burden of diabetes through public health leadership, partnership, research, programs, and policies that translate science into practice”, by “improving the rapidity and extent of transfer of validated research findings into the practice of medicine” in as short a time as possible. Subsequently, various US universities established divisions and centres of clinical and translational science.

By 1994, when the National Cancer Institute in the US initiated SPORE (the Specialized Program of Research Excellence), to encourage translational research in the management of certain cancers, authors were starting to use the term “translational research” in the titles of their papers. Others started to use the terms “translational medicine” in 1996 and “translational science” in 2003, when the first journal with “Translational” in its title was published. By 1996 some were moved to suggest that translational research had “come of age”, while nevertheless describing it as a “buzzword”, while others called it a “catch phrase . . . exciting . . . but laden with booby traps”.

Next week I shall discuss early definitions and models of translational research.

Jeffrey Aronson is a clinical pharmacologist, working in the Centre for Evidence Based Medicine in Oxford’s Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. He is also president emeritus of the British Pharmacological Society.

Competing interests: None declared.