Health, as we all know but are inclined to forget, is driven not by healthcare but by social determinants. But how do you produce social determinants that promote rather than undermine health? Political action is one way, but another is to strengthen communities. Jennifer Miller, chief executive of the Global Climate and Health Alliance, described what she has learnt about the difficult art of community strengthening at a C3 Collaborating for Health breakfast earlier this week.

Health, as we all know but are inclined to forget, is driven not by healthcare but by social determinants. But how do you produce social determinants that promote rather than undermine health? Political action is one way, but another is to strengthen communities. Jennifer Miller, chief executive of the Global Climate and Health Alliance, described what she has learnt about the difficult art of community strengthening at a C3 Collaborating for Health breakfast earlier this week.

Miller began her career like most in public health by working with communities to try and reduce asthma, obesity, and non-communicable disease (NCDs). In tune with the times she saw obesity as an issue of “personal responsibility,” but she soon recognised that people are obese largely as a result of their physical and social environment. Similarly it makes little sense to try and counter asthma without considering indoor and outdoor air pollution.

The next step for Miller was to recognise the interconnectedness of health and climate change. The report NCDs and Climate Change: Shared Opportunities for Action made clear that the causes of climate change and the pandemic of NCDs are essentially the same—overuse of transportation, intensive farming and overconsumption of unhealthy foods, and excessive energy consumption. Climate change is, as the Lancet has argued, the greatest threat to public health, but responding to it provides a huge opportunity to improve public health.

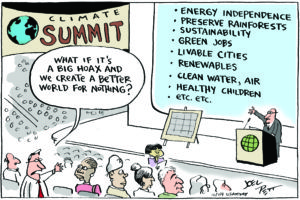

Miller showed a cartoon with a speaker at a conference on climate change showing a slide advocating energy independence, preserving rainforests, sustainability, green jobs, livable cities, renewables, clean air and water, and healthy cities and somebody in the audience asking “What if it’s a big hoax and we create a better world for nothing?” (The joke is particularly poignant six days into the presidency of Donald Trump.)

Miller showed a cartoon with a speaker at a conference on climate change showing a slide advocating energy independence, preserving rainforests, sustainability, green jobs, livable cities, renewables, clean air and water, and healthy cities and somebody in the audience asking “What if it’s a big hoax and we create a better world for nothing?” (The joke is particularly poignant six days into the presidency of Donald Trump.)

NCDs and Climate Change: Shared Opportunities for Action made three key points: social determinants underpin both NCDs and vulnerability to climate change in poor communities; “holistic, place based” strategies can improve health and reduce vulnerability to climate change; and such approaches are essential to improve health, equity, and the environment.

A quarter of the US population lives in “high poverty areas,” where more than a fifth of the population meets the federal definition of poverty (and you have to be very poor to meet the definition). One in four African Americans, one in six Hispanics, and one in eight Native Americans live in areas where 30% of the population is poor. These areas lack jobs, good schools, high quality housing, a clean environment, banks and financial services, clinics, access to healthy food, security, and social cohesion.

Research has shown that such an environment—independent of individual and family characteristics—is associated with high rates of infectious disease, poor birth outcomes, unhealthy children, cardiovascular disease, obesity, depression, and unhealthy behaviours. In other words, people living in these communities have a double hit—from their own poverty and from their environment.

People who live in these areas are also much more vulnerable to climate change. “Vulnerability” is a function of being more likely to be exposed to the harm, being more sensitive to its impact, and less able to adapt. Think of the effects of Hurricane Katrina on New Orleans: the poorest areas suffered the most damage and have been the slowest to recover.

But how to strengthen communities? There is no simple formula, and it’s hard to achieve and sustain. But one given is that the priorities must be driven by what matters to people in these communities—and it’s unlikely to be NCDs or obesity. They have other, more immediate concerns. Health—at least in the narrow way we tend to think about it—will be improved usually as a side effect of broader improvement in the community.

Miller described three communities that have succeeded in making great improvements, and each succeeded in a different way.

East Lake, Atlanta, Georgia

Improvement in East Lake in Atlanta, Georgia, was driven initially by a local business leader. East Lake was known locally as “Little Vietnam,” not because Vietnamese lived there but because it was like a war zone. Many of the local children ended up in prison. The business leader created a foundation, which had funding from various sources, including the State; and he spent two years convincing a local woman who was widely respected in the community to be a leader.

The first step was to build high quality, mixed income housing where rich and poor had the same units. Next they developed green spaces where children could play and a “walkable” environment. A member of the audience emphasised that architects, designers, and urban planners play a vital role in improving communities.

An odd feature of the programme was the development of a world class golf course from what was a rundown course. It provided income to the community, and a public golf course allowed local people to play.

A more conventional development was to provide cradle to grave education with preschool education and after school programmes. Education is one of the best counters to vulnerability.

This development began long ago, and the results are that violent crime has fallen by 95%, numbers on welfare has fallen from 59% to 5%, 98% of children are meeting or exceeding State standards for reading, writing, and maths, and more children are going to college. “We tore down hell and built heaven,” said the local leader.

Refresh, New Orleans, Louisiana

Refresh in New Orleans was badly damaged by Hurricane Katrina, and the community decided that they wanted to rebuild but not what went before. They sought outside help and concentrated on the availability of healthy foods. The company Whole Foods started a shop there—but one that was different from the shops they had in high income areas, not least in providing healthy food that was more affordable. Tulane University helped by contributing medical students who trained people in healthy cooking after themselves being trained at the Goldring Center for Culinary Medicine. The premise of the centre is that doctors might know something about nutrition [although not much, I can’t resist adding] but little or nothing about foods and cooking. The community also created a community garden and urban farm and has promoted small businesses and local clubs.

One consequence of improving an area, turning it from hell to heaven, is “gentrification”: property prices rise, and poor locals are driven out. Some gentrification is a good thing in that it leads to a mixed community and brings in more resources, but getting the balance right is hard.

Little Village, Chicago, Illinois

Improvements in Little Village, Chicago, which is mainly Mexican, were driven from the grass roots and by opposition to the pollution from two of the “oldest and dirtiest” coal power stations in the US. A local activist was convinced that the power stations were making local people sick but made little progress with activating the community until a study by Harvard University showed that the power stations were killing 40 people a year and causing 2800 more hospital admissions for asthma. These findings galvanised the community and led to the power stations being shut in 2012.

At the same time the community created some 500 new local businesses and built a vibrant, resilient community centred around Mexican culture.

Dickens, Los Angeles, California

As I listened to these accounts of rundown communities regenerating themselves, I couldn’t help thinking of the “regeneration” of Dickens, an African American ghetto described in The Sellout, the novel that won last year’s Man Booker Prize. It’s a marvellous satire that describes the community, which at one point disappeared from the map, being regenerated by reintroducing slavery (well, one slave) and segregation. It’s a novel to rank alongside Gulliver’s Travels and Catch 22, and I’ve written about it on my own blog.

Conclusions and questions

Miller concluded with a list of the essentials a community needs to improve health and to mitigate and promote resilience to climate change: high quality housing, good schools, individual and community economic development, access to healthy food, a clean environment, access to healthcare, green spaces, “walkability,” public transport, security, civic engagement, and social cohesion.

An obvious question is whether this can be done on a large enough scale. There are thousands of deprived communities in the US: how many are being revitalised? Miller didn’t know the answer, but she said that some $250 billion is being invested in communities in the US. She doubts that that’s enough.

And what will the election of President Trump mean for these communities? Aren’t they the “forgotten people” he wants to help? But he thinks that climate change is a hoax, and the day before the meeting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention cancelled a meeting on climate change. Miller thought that his election would be “entirely challenging”

Richard Smith was the editor of The BMJ until 2004.

Competing interest: RS was on the board of C3. He was not paid.

Cartoon: Copyright Joel Pett. Reprinted with permission.