“Get something out on social?” urged a colleague in response to UK Chancellor George Osborne’s sugar tax announcement in his Budget speech last week. “I think you can claim that as a ‘win’ for The BMJ” added another after we reminded him of the many articles we have published on the sugar tax.

“Get something out on social?” urged a colleague in response to UK Chancellor George Osborne’s sugar tax announcement in his Budget speech last week. “I think you can claim that as a ‘win’ for The BMJ” added another after we reminded him of the many articles we have published on the sugar tax.

We quickly got tweeting, and updated our website homepage with links to some of the articles we have published about sugar taxes over the years. This includes a call from our editor in January 2016 to listen to the evidence in response to a study we published about Mexico’s tax on sugar sweetened drinks.

So was it The BMJ wot won it, (to steal a famous headline from UK tabloid The Sun  after it claimed credit for the Conservative Party surprise win in the 1992 election)? Did politicians read our content, and did it influence their decision? We routinely ask readers in our annual reader survey if the journal has helped them make better decisions. Maybe we should ask politicians too.

after it claimed credit for the Conservative Party surprise win in the 1992 election)? Did politicians read our content, and did it influence their decision? We routinely ask readers in our annual reader survey if the journal has helped them make better decisions. Maybe we should ask politicians too.

Osborne’s new tax on drinks containing sugar is expected to raise £520m (€658m; $744m) a year when it comes into force in 2018. The revenue will be used in part to double the amount primary schools spend on sport, to £320m a year.

Junior doctor Rachel Remnant reacted with cynicism to the news in a response posted over the weekend: “I am cynical that the added expense itself of sugar-sweetened soft drinks will have the same effect, she wrote. “My primary concern with these new proposals is not the efficacy however but the restriction of freedom of choice…There are few areas in public health where I believe we are entitled to use the stick rather than the carrot. In this case, we are merely discriminating according to wealth and the ability to pay this tax.”

A sugar tax in the US

The journal has covered the debate extensively over the years. As far back as 2010 our US columnist Doug Kamerow was describing the food industry’s response to a proposed tax on sugar sweetened beverages (SSBa) in America.

“In cities and states where SSB taxes have been proposed, industry financed ‘grassroots’ organisations sprang up out of nowhere with names like ‘New Yorkers against Unfair Taxes’ and ‘NoDCBevTax.com,’ ” Kamerow wrote.

Mexico’s experience

In January 2016 the aforementioned study investigated the effect on purchases of beverages from stores in Mexico one year after implementation of an excise tax on sugar sweetened beverages. The excise tax of 1 peso per litre on sugar sweetened beverages was introduced on 1 January 2014.

The researchers found the tax was associated with an overall 12% reduction in sales and a 4% increase in purchases of untaxed beverages, but emphasised that because it is observational study, no definitive conclusions can be drawn about cause and effect.

They also point to some study weaknesses, such as incomplete data on dairy beverages and their focus on Mexican cities.

Nevertheless, they conclude that this short term change “is moderate but important” and they say continued monitoring is needed “to understand purchases longer term, potential substitutions, and health implications.”

Franco Sassi, head of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) said in a linked editorial that the study did not explore whether a 1 peso per litre tax is large enough to achieve meaningful health benefits. To assess this, population models are needed.

Sassi added: “Taxes do have a place in a broader strategy in countries that are facing disproportionate harms from unhealthy diets, but having to make people pay for their potentially unhealthy consumption choices is not a success for public health.”

Could a sugar tax help combat obesity?

In July 2015 the journal published a head to head article asking if a sugar tax could help combat obesity?

In Finland, a sugar tax working group concluded: “A combination of excise duty for key sources of sugar with tax adjusted based on sugar content would optimally promote health – and product reformulation.”

Sirpa Sarlio-Lähteenkorva, adviser at the ministry of social affairs and health in Finland, argued that taxes on specific food categories that are common constituents of poor diets “are practicable because they are simple to administer, adding; “Increasing evidence suggests that taxes on soft drinks, sugar, and snacks can change diets and improve health, especially in lower socioeconomic groups.”

But Jack Winkler, emeritus professor of nutrition policy at London Metropolitan University, argued at the time that such taxes are politically unacceptable and economically ineffective. Conservative politicians had promised not to introduce any new food taxes, he said. They have now.

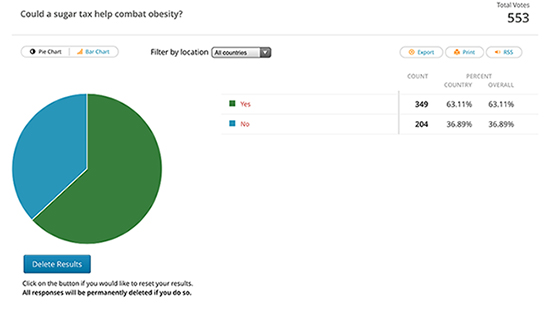

We asked readers what they thought via an online poll. Of the 553 votes, 63% (349 votes), said yes. We also ran a poll asking if a sugar tax should be imposed on food and drink sold in hospitals. Of the 1139 votes cast, 67% (767) said yes.

A cautionary note

Sometimes, of course, politicians do use data from The BMJ, most recently when editor in chief raised concerns that England’s health secretary Jeremy Hunt had misused data in an article relating to the deaths of patients admitted to hospitals at weekends.

But that’s another story.

More sugar tax articles from The BMJ

- Headline writers find sweet spot with sugar tax

- Taxing unhealthy food and drinks to improve health

- The case of the sugar sweetened beverage tax

- Overall and income specific effect on prevalence of overweight and obesity of 20% sugar sweetened drink tax in UK: econometric and comparative risk assessment modelling study

- Taxing sugar

David Payne is digital editor and readers’ editor, The BMJ