This flu season, Influenza A (H3N2) has been the dominant circulating strain, with transmission occurring unusually early (November and December). By December 2014, influenza rates were higher than they had been in the previous three years. However, recent research by Public Health England (PHE) suggested that there was a mismatch between the H3N2 strain selected for this year’s vaccine and the H3N2 that is circulating in the UK this winter. [1] This was based on an assessment of the vaccine effectiveness (VE) which was estimated to be only 3.4% (95%CI -44.8 to 35.5) against laboratory confirmed influenza (all types) and -2.3% (95%CI of -56.1 to 33.0) for Influenza A (H3N2). This is in comparison to the estimated average VE of influenza vaccines of 59%. [2] Furthermore, the VE for the same vaccine in Canada this season is also effectively zero, being estimated as -8% (95% CI:-50 to 23) but in the United States it appears to have a moderate effect, being estimated at 22% (95% CI 5 to 35). [3]

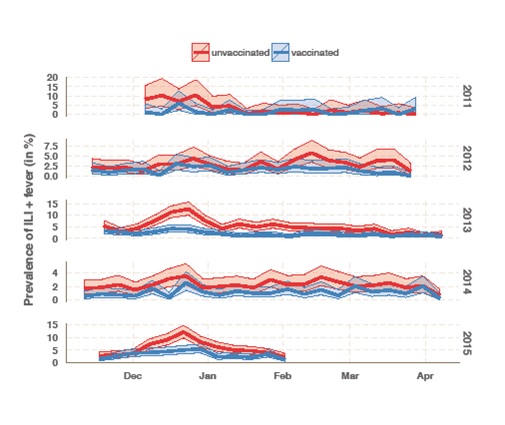

Flusurvey is an online participatory surveillance system allowing participants to report influenza like symptoms on a weekly basis, in an effort to establish the real-time rate of influenza-like illness (ILI) in the UK at any one time. By comparing cohorts of vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals (matched for other variables, such as age, sex, risk group, and living with children), Flusurvey is able to analyse VE against self-reported ILI in close to real-time (see figure). The method can be supplemented by a regression analyses in which the same covariates as PHE’s data (age, sex, risk group, living with children, month of onset) are used to estimate VE. Yet the vaccine effectiveness amongst the Flusurvey participants has been at odds with PHE’s results. The chart below represents vaccine effectiveness during this five year time period.

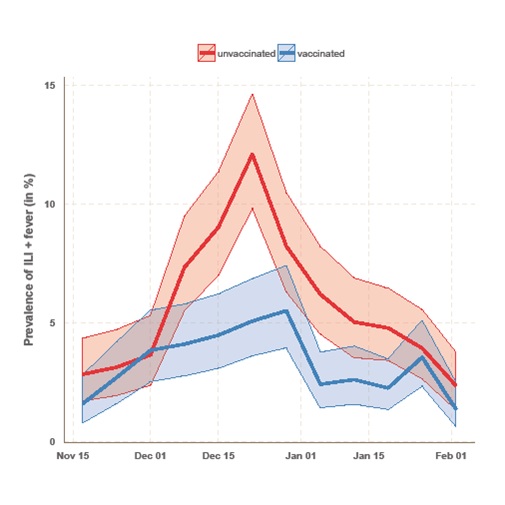

PHE laboratory testing confirmed that the strain circulating in December (during the peak of this year’s flu season) was Influenza A (H3N2). [4] By the end of December, PHE respiratory virus unit has tested isolated and antigenically characterised 22 Influenza A (H3N2) viruses, 19 of which were similar to the A/Texas/50/2012/H3N2 Northern Hemisphere 2014/5 vaccine strain, and only 3 of these viruses tested showed signs of a drifted virus. Although this is a very small sample size, so caution should be applied in extrapolating this to the population level, it would imply that in fact, there was a match between the strain circulating and the vaccine this season. Unlike the analysis run at PHE, our data show that there was a disparity in prevalence of ILI and fever between those who had been vaccinated and those who had not. This suggests that the vaccine was, in fact, offering some protection against influenza-like symptoms this season. Having said that, the number of samples which have been tested at PHE has increased since December, as has the number which show signs of reduced reactivity to the antigenic tests with A/Texas/50/2012/H3N2 antiserum to 52/220 Influenza A (H3N2). [5] This may suggest that the vaccine effectiveness may have reduced over the course of the season.

It must be noted that the data collected by Flusurvey are of influenza like illnesses (ILI) rather than laboratory confirmed cases of influenza A or, more specifically, H3N2. However, the peak of our reported symptoms does match the peak flu rates seen by PHE this season (weeks 51&52), and the incidence of ILI in the two groups (flu-vaccinated and unvaccinated) only diverges during the peak flu-season (December). Taken together this is strongly suggestive that many of the ILI cases reported by participants in December were indeed influenza, and that the vaccine had some effect. Clearly, much of this mystery could be solved if Flusurvey participants also gave samples that could be tested virologically. And indeed, this is exactly what we are now doing. For the first time Flusurvey is running a pilot of self-swabbing to determine whether the symptoms reported online by participants are being caused by an influenza virus, or by something else. The results of this will be shared shortly. However, it remains puzzling that we are seeing a discrepancy in vaccine effectiveness compared to PHE and we shall look forward to investigating this further.

Clare Wenham is a research fellow in public health engagement at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Her research focuses on novel methods of disease surveillance and she is currently working for UK Flusurvey.

Clare Wenham is a research fellow in public health engagement at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Her research focuses on novel methods of disease surveillance and she is currently working for UK Flusurvey.

Professor John Edmunds is the Dean of the Faculty of Epidemiology and Population Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. His research focuses on the transmission and control of infectious diseases. He helped set up the UK Flusurvey during the 2009 swine flu pandemic and has been involved with it ever since.

Professor John Edmunds is the Dean of the Faculty of Epidemiology and Population Health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. His research focuses on the transmission and control of infectious diseases. He helped set up the UK Flusurvey during the 2009 swine flu pandemic and has been involved with it ever since.

Competing interests: CW: None declared. JE: My partner works for GSK.

Funding: The authors received funding for their research from i-sense.

References:

1) Pebody et al, (2015), Low Effectiveness of Seasonal Influenza Vaccine in Preventing Laboratory Confirmed Influenza in primary car in the UK:2014-15 Mid-Season results, Eurosurveillance, Vol 20, Issue 5, 05 Feb 2015.

2) Osterholm et al (2012) Efficacy and Effectiness of influenza Vaccines: A systematic review and meta analysis, The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Vol 12, Issue 1, January 2012, pp 36-44.

3) Pebody et al, (2015), Low Effectiveness of Seasonal Influenza Vaccine in Preventing Laboratory Confirmed Influenza in primary car in the UK:2014-15 Mid-Season results, Eurosurveillance, Vol 20, Issue 5, 05 Feb 2015.

4)https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/390846/Weekly_report_current_week_52.pdf

5)https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/414601/Weekly_report_current_week_12_19March2015.pdf