On learning about the source of the colour of Anna Dumitriu’s quilt, some people feel distinctly uncomfortable, and a few have even said, “But that’s irresponsible! That’s dangerous!”

On learning about the source of the colour of Anna Dumitriu’s quilt, some people feel distinctly uncomfortable, and a few have even said, “But that’s irresponsible! That’s dangerous!”

The blue doesn’t come from indigo or from a new type of powder—and the way it’s used is definitely not irresponsible or dangerous. Although the colour comes from MRSA bacteria (“superbugs”), the colouring process was carried out in a laboratory, under optimal safety conditions.

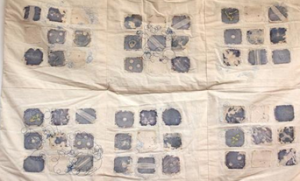

MRSA Quilt (photo from annadumitriu.tumblr.com/NormalFloraExhibition). Before leaving the lab, the fabric was treated at high temperatures to kill the bacteria. The bacteria are dyed blue because they are grown on chromogenic agar, which contains the dye and which soaks into the cloth. As the agar feeds the bacteria, they take up the dye, become blue, and colour the cloth.

MRSA Quilt (photo from annadumitriu.tumblr.com/NormalFloraExhibition). Before leaving the lab, the fabric was treated at high temperatures to kill the bacteria. The bacteria are dyed blue because they are grown on chromogenic agar, which contains the dye and which soaks into the cloth. As the agar feeds the bacteria, they take up the dye, become blue, and colour the cloth.

Dyeing in progress at a public workshop; the plates were taken back to the lab and grown with bacteria (photo from annadumitriu.tumblr.com).

Dyeing in progress at a public workshop; the plates were taken back to the lab and grown with bacteria (photo from annadumitriu.tumblr.com).

The embroidery thread used in the quilt is coloured with safflower and turmeric—and (in some cases) impregnated with the antibiotic vancomycin, which is considered to be a “last ditch” antibiotic for treating MRSA infection.

Anna Dumitriu’s unusual dyestuffs are an outcome of an ongoing artist in residence project—initially funded by the Leverhulme Trust Artist in Residence Award in 2011, and by the Wellcome Trust and Arts Council England—at the Modernising Medical Microbiology Project at the University of Oxford, in partnership with Public Health England. She works by shadowing scientists on the project, learning hands on techniques, and investigating their work.

Anna’s exhibition in London earlier this year included other objects dyed with natural dyes: dyestuffs that were also used as medicines, or which perhaps became dyestuffs as a by-product of being used as medicines. Madder root for pink/brown, safflower giving yellow or pink, and walnut husks for brown shades . . . these dyes were also used as ancient treatments for tuberculosis.

Textile dyes are specifically involved in the history of drug treatment. In the 1930s, the dye company Bayer worked on the idea that coal tar dyes might be used to treat harmful substances in the body. The bacteriologist Gerhard Domagk came up with a bright orange substance that they called Prontosil, which, before antibiotics were widely developed, was hailed as a wonder drug and widely used in World War Two to prevent infection.

The Romantic Disease Dress (photo from theromanticdisease.tumblr.com/dress).

The Romantic Disease Dress (photo from theromanticdisease.tumblr.com/dress).

Anna has used Prontosil to stain embroidery on the back shoulders of an antique maternity dress, which was impregnated with the extracted DNA of killed tuberculosis bacteria. She dyed the dress with walnut husks, and dyed the embroidery threads and ribbons with madder root and safflower.

Where there’s dust there’s danger (photo from annadumitriu.tumblr.com/RomanticDisease).

Where there’s dust there’s danger (photo from annadumitriu.tumblr.com/RomanticDisease).

Also part of the project on tuberculosis (the world’s largest infectious killer) are little felted lungs. “Where there’s dust there’s danger,” advised the Society for the Prevention of Consumption in 1902 (incorrectly, as it turned out). Basing the lungs on this long held misconception, Anna made them with felting wool and household dust, then impregnated them—as she had the antique dress—with DNA that had been extracted from killed TB organisms. The DNA is dead so it’s not harmful; there is no risk of infection from the little lungs, just a “memory” of being contaminated.

Genius Germ (photo from theromanticdisease.tumblr.com/GeniusGerm).

Genius Germ (photo from theromanticdisease.tumblr.com/GeniusGerm).

A recent project, made especially for a show at the Picasso Museum in Barcelona, is inspired by Picasso’s painting of about 1899, which shows a group of people around the bed of a very sick patient. An antique doll’s bed from the same period has been altered and given a quilt, created using squares of natural dyed fabric and threads treated with antibiotics and antibacterials, and grown with environmental bacteria (the quilt has been sterilised by autoclaving). The antique crochet pillow has been dyed with walnut husks, and the bedstead patterned to indicate the patient’s degenerating lung tissue.

The use of germs, the dusty lungs, the MRSA quilt: all give rise to horror struck reactions. Part of Anna’s purpose in making these art works through her scientific art residencies is to use these objects as a kind of storytelling and to involve viewers in health issues—a way to spread not germs but knowledge.

Anna Dumitriu’s exhibition “[micro]biologies I: the bacterial sublime” is on at Art Laboratory Berlin until 30 November 2014.

After two decades at The BMJ as a technical editor, Margaret Cooter went on to art school, obtaining an MA from Camberwell (University of the Arts London) in 2012.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: none.