Flexor and Extensor (tendon) hand sports injuries are a common reason for presentation to the emergency department. They often involve trauma, and can impact an athletes ability to grip, perform activities of daily living and also function post injury. The early identification of these injuries with a focused clinical examination, and appropriate imaging help to restore function early, preserve alignment and prevent long term disability. We discuss the key tendon injuries to look out for in the field of play, and pathways for both non-surgical and surgical management.

Hand injuries in sport

Hand injuries are a common occurrence in impact sports and often under-appreciated on the field of play. Whilst there is tendency to “relocate” or “strap up” and play on with a hand injury – early diagnosis, immediate care and treatment can help to preserve function in athletes.

|

Is this an acute or chronic injury? |

|

|

Key questions |

How will it help me ? |

|

Is the wound open ? |

Early antibiotic treatment, closure +/- exploration |

|

Is there a possible fracture ? |

Arrange X-ray imaging |

|

Is this a flexor or extensor tendon injury ? |

This can help to assess timelines for healing |

Table 1. Key considerations

Taking a clear acute injury history from the player can help you to diagnose and plan treatment early on after presentation. It will also help to guide your referral.

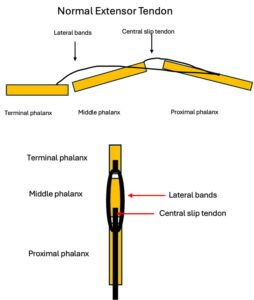

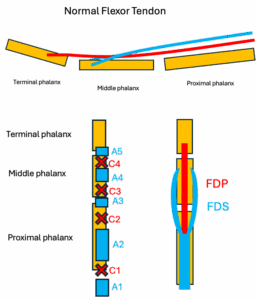

Figure 1. Anatomy of extensor and flexor tendons, alongside some common injuries

Figure 2. Extensor tendon anatomy

Figure 3. Common extensor tendon injuries

Figure 4. Flexor tendon anatomy

Figure 5. Ultrasound scan of digit.

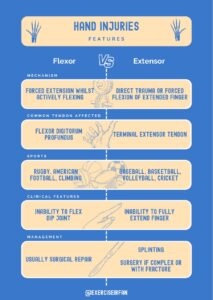

| Feature | Flexor Tendon Injuries | Extensor Tendon Injuries |

| Mechanism | Forced extension while actively flexing | Direct trauma or forced flexion of extended finger (e.g., “mallet finger”) |

| Common Tendon Affected | Flexor digitorum profundus | Terminal extensor tendon |

| Sports | Rugby, American football, climbing | Baseball, basketball, volleyball, cricket |

| Clinical Features | Inability to flex DIP joint | Inability to fully extend finger |

| Management | Usually surgical repair (poor healing without it) | Often splinting; surgery if complex or with fracture |

| Recovery/Prognosis | Longer rehab, higher risk of stiffness/adhesions | Shorter recovery, generally better prognosis |

Table 2. Breaking down extensor and flexor hand injuries.

Mechanism of injury

Hand tendon injuries are common in both sporting patients and those undertaking recreational activities (DIY) or manual professions that put their hands at risk. Although ball sports (football, rugby, basketball, cricket, baseball) are the most reported sports for these injuries, they are also seen in contact and combat sports such as martial arts and boxing.

In ball sports the fingers are typically exposed to sudden impacts or unsupported forced movements (1) whereas, direct blows or forced grip injury mechanisms are more predominant in contact sports. Manual professionals or those working with sharp tools, may be at risk of lacerations that can cause tendon ruptures and significantly impair grip, fine motor control and dexterity.

Recognising the mechanisms of injuries early and potential structures involved is key to preventing chronic disability (2) and involves an MDT approach.

|

Injury |

Mechanism / Force |

Typical Deformity Seen |

Healing Timeline |

|

Finger |

Forced flexion of extended DIP (e.g. ball striking at the fingertip) |

Drooping fingertip (loss of DIP extension) |

Splint DIP in extension for 6–8 weeks Surgery if sub-luxed or large fragment |

|

Dislocation |

Axial load, hyperextension or twisting |

Finger angulated, obvious deformity, severe pain |

Closed reduction follow up buddy taping or splinting, Surgery if unstable *XRAY ( pre- and post-reduction) |

|

Jersey finger |

Forced extension while actively flexing (e.g. grabbing jersey) |

Inability to flex DIP (finger remains extended) |

Surgery ideally <10 days followed by 12+ weeks rehab |

|

Boutonniere |

Forceful blow to dorsal PIP joint while finger is flexed |

PIP flexion + DIP hyperextension |

Splint PIP in extension for 6 weeks. Surgery if chronic or displaced |

|

Trigger finger |

Repetitive gripping, stenosing tenosynovitis at A1 Pulley |

Painful locking/catching on flexion |

Weeks–months (conservative), Consider Steroid injection A1 pulley release if refractory |

|

Extensor hood / sagittal band rupture |

Forced flexion against resistance, or direct blow (e.g. boxer’s knuckle) |

Extensor tendon subluxation/instability at MCP |

6–8 weeks splinting, Surgery if unstable |

|

Flexor tendon injury |

Laceration, forced extension, crush |

Inability to flex affected joint(s) |

Surgical repair → 12 weeks+ rehab |

|

Volar plate injury |

Hyperextension at PIPJ |

Swelling, PIP instability, hyperextension |

4–6 weeks splinting, progressive rehab |

Table 3. Common injury patterns seen in the Emergency Department

The Patient’s journey from injury to treatment usually involves care at the pitch side (where medical assistance is available) or presentation at the Emergency Department. It is important that immediate treatment is provided to stabilise the injury, start treatment (in suspected open fractures), and assess for neurovascular compromise.

| Mallet Finger

DIP “droop” (cannot actively extend). Swelling or tenderness to the DIP in Acute cases (often absent in chronic cases) but a persistent extensor lag will be evident. Imaging X-ray: A 3-view radiographic series (anteroposterior, oblique, and true lateral) is recommended. US: extensor tendon discontinuity (consider where available) |

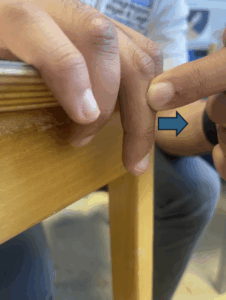

Mallet Finger test:

The patient will be asked to extend their finger whilst their finger is at the edge of a table. If the patient is unable to fully extend their finger independently, it indicates a mallet finger injury.

|

| Jersey Finger

Pain and tenderness of the volar aspect of the injured finger Ask patient to make a fist → affected DIP won’t flex. “Sweater/Jersey sign.” Imaging X-ray: Plain radiographs to rule out fractures US: To assess for tendon retraction in both acute and chronic cases without fracture MRI is rarely performed but can be used to determine the increased tendon-bone distance more accurately. |

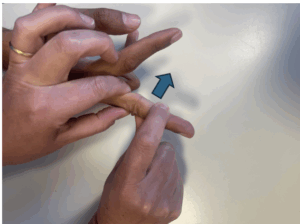

Jersey Finger Test:

The clinician holds the patient’s proximal interphalangeal joint (middle joint) in full extension and asks the patient to bend (flex) the Distal Interphalangeal joint (DIP) Intact FDP: If the patient is able to flex the DIP, the FDP is intact Ruptured FDP: If the patient is unable to flex the DIP, the FDP if likely ruptured

|

| Boutonniere

Pain and swelling of the PIP Elson’s test: flex PIP over table, resist extension → weak at PIP, DIP hyperextends. Inability to actively straighten the middle joint of the finger. Imaging X-ray: exclude fracture. US/MRI: central slip disruption, extensor hood injury. |

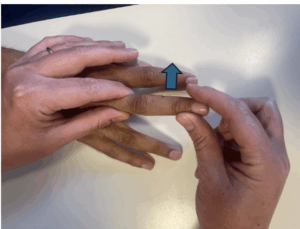

Elson test:

The patient will rest their finger at the edge of the table, with the affected proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) resting in 90 degrees flexion. The clinician presses on the middle phalanx. The patient is asked to extend their PIP against the clinician finger. Positive test: The patient has a weak PIP and the DIP becomes rigid and or even hyper extension. This indicates the an injury to the central slip due to the extension force travelling to the lateral bands and extending the DIP Negative test: The patient can extend the PIP against resistance and the DIP joint remains floppy and flexible suggesting the central slip is intact.

|

| Trigger finger

Palpable nodule at A1 pulley. “Locking/catching” on flexion-extension cycle. Imaging US : dynamic ultrasound can be used to look for tendon thickening and dynamic bunching underneath pulley |

Trigger finger test:

The clinician will ask the patient to move their finger to feel for any locking or catching. The clinician will feel the base of their finger or thumb to check for a palpable lump. The clinician may also try to passively extend or flex the finger to see how the tendon moves.

|

| Extensor hood rupture (sagittal band rupture)

Extensor tendon subluxation when flexing/ extending MCP. Pain/tenderness sagittal band. Imaging US/MRI: discontinuity or subluxation of extensor tendon over MCP. |

Elson test:

The patient will rest their at the edge of the table, with the affected proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP) resting in 90 degrees flexion. The clinician presses on the middle phalanx. The patient is asked to extend their PIP against the clinician finger. Positive test: The patient has a weak PIP and the DIP becomes rigid and or even hyper extension. This indicates the an injury to the central slip due to the extension force travelling to the lateral bands and extending the DIP Negative test: The patient can extend the PIP against resistance and the DIP joint remains floppy and flexible suggesting the central slip is intact.

|

| Flexor tendon Laceration

Ask for isolated PIP/DIP flexion → loss suggests FDS/FDP injury. Assess neurovascular status. Imaging US – loss of tendon continuity XR – to rule out fracture |

Flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) test:

The clinician holds the other three fingers in full extension to prevent the flexor digitorum profundus from working. The patient is asked to flex their finger at the PIP joint. Positive test: If the PIP does not bend or bends poorly it suggests an injury to the FDS. Negative test: If the PIP joint flexes and the DIP remains lax or straight, it suggests the FDS is intact.

Jersey Finger Test (FDP): The clinician holds the patients proximal Interphalangeal joint (middle joint) in full extension and asks the patient to bend (flex) the Distal Interphalangeal joint (DIP) Intact FDP: If the patient is able to flex the DIP, the FDP is intact Ruptured FDP: If the patient is unable to flex the DIP, the FDP if likely ruptured

|

| Volar plate injury

Tender at volar PIP, instability with hyperextension stress test. X-ray: avulsion fragment, joint subluxation. MRI if uncertain ligament/volar plate injury. |

Volar plate stress test:

The clinician will apply directed force to test for instability. Increased laxity or a gross dislocation during the force suggests a tear or avulsion to the volar plate.

|

Table 4. Common tendon injuries, their clinical findings and relevant imaging.

Remember:

Is there an open wound or visible tendon?

- If yes – refer to Hand Surgeon

- If no – Continue

Is there loss of extension or flexion?

- Extension loss – extensor Pathway

- Flexion loss – Flexion Pathway

Figure 6. Key questions for hand injuries

Figure 7. Flowchart of flexor or extensor tendon injuries

Figure 8. Management of common flexor and extensor hand injuries

When to Image

- Consider X-Ray if subluxation, bony avulsion or traumatic mechanism suspected

- Use Ultrasound for dynamic tendon integrity (if available)

—————————————————————————————————-

Red Flags – Urgent Hand Surgeon Referral

- Open tendon injuries

- Neurovascular compromise (loss of sensation, absent pulse, white finger)

- Suspected complete tendon rupture

- Joint dislocation/ subluxation with tendon injury

- Delayed presentation (more than 7-10 days for FDP avulsion+ poorer prognosis)

Clinical Assessment and Imaging

When hand injuries present to the Emergency Department – a concise history that includes the mechanism of injury, handedness, and sporting/occupational demands is advised. If there is a suspected fracture then plain film x-ray imaging in at least two views to rule out bone involvement (fractures, dislocations and subluxations) is essential

Checklist for hand injuries presenting to the Emergency department.

– History including mechanism of injury, handedness, hobbies

– Washout of wound (if present)

– Clinical examination

– Plain film x-rays (rule out concurrent bony injury)

– Discussion with hand surgery team

*(Plastics surgery or Orthopaedic surgery depending on local expertise) for further investigation and surgical planning within 24 hours. (BSSH, 2024).

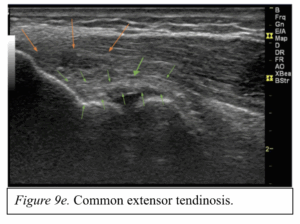

A focussed hand specific clinic assessment (table 4) can help to rule in or out complete ruptures but is less sensitive for (partial tears). Where a closed tendon rupture is suspected and the clinical exam is uncertain, imaging can help to confirm a diagnosis. MRI is the gold standard imaging for closed tendon injuries and has good sensitivity, but US is generally preferred as it allows the benefit of dynamic assessment of tendons, locating retracted tendon ends and more chronic conditions, such as tendinopathy or tendinosis (Figure 1-2).

Open injuries do not often need imaging and are usually explored surgically. Ideally, tendon injuries should be repaired within 4 days of the injury (BSSH, 2024) and if an US scan is not available during this time frame, then it is better to continue with surgical exploration +/- repair.

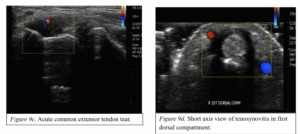

Figure 9. Ultrasound images of various tendinous pathologies.

Definitive Management

Treatment options differ slightly depending on the mechanism of injury. General rule of thumb is that traumatic tendon injuries, tendon injuries with fractures and tendon injuries that have failed conservative management require surgical repair. Tendon rupture requires surgical intervention called a primary repair. More complex cases with missing tendon or post-operative complications may need a tendon transfer or a two-stage repair.

Table 5. Definitive management of common extensor and flexor injuries

| Compartment | Injury | Injured Structure | Management |

| Extensor | Mallet finger | Extensor tendon insertion at distal phalanx |

|

| Boutonniere | Central slip of extensor tendon at middle phalanx |

|

|

| Extensor hood/sagittal band rupture | Sagittal bands stabilising extensor tendon at MCP |

|

|

| Extensor tendon injury | EDC/EDM/EDI tendons |

|

|

| Flexor | Jersey finger | FDP insertion at distal phalanx |

|

| Trigger finger | Flexor tendon sheath at A1 pulley |

|

|

| Flexor tendon injury | FDS/FDP tendons (commonly Zone III – “no man’s land”) |

|

|

| Other | Volar plate injury | Volar plate +/- collateral ligaments |

|

| Dislocation | Potentially injure: Capsule, collateral ligaments, volar plate |

|

Peripheral Nerve Blocks

Equipment

Equipment: 10mL syringe, 10mL lidocaine 1% vial, skin preparation wipes, drawing up needle, small needle (e.g 25G)

General Tips

– Needles are always inserted perpendicular to the skin surface

– None of these nerves are particularly deep at the locations where blocks are performed so no need to go too deep!

– Positioning for the blocks is always laying hand flat on either the volar or dorsal side (except from the radial nerve block)

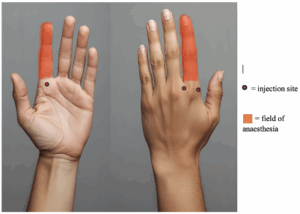

Ring block:

– Bear in mind that there are many ways to do a digital nerve block!

Technique:

- Insert needle just proximal to the crease at the base of the digit until you hit bone

- Retract slightly (2mm)

- Inject 2-3mL of lidocaine

- Retract slightly until the needle is just under the skin and inject another 2mL

- Turn the patient’s hand over

- Insert needle around 1cm and inject 1-2mL whilst withdrawing on either side of the extensor tendon

Figure 10. Image demonstrating the injection site and anaesthetic field for ring blocks.

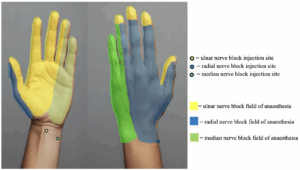

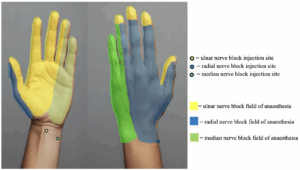

Ulnar nerve block:

Technique:

- Palpate the flexor carpi ulnaris (ulnar-most tendon of the anterior wrist) at its insertion on pisiform, just proximal to the distal wrist crease

- Move 3-4cm proximally, this is your landmark

- Clean the skin

- Insert the needle parallel to the table just inferior to the tendon, making sure to not insert in the tendon

- ASPIRATE (the ulnar artery is in the same space)

- Inject anaesthetic (2-3mL is usually enough)

Median nerve block:

- Ask the patient to touch their little finger and thumb whilst flexing the wrist, accentuating the palmaris longus tendon (ulnar side) and flexor carpi radialis tendon (radial side). The median nerve is directly in between them.

- Clean the skin

- Insert the needle 5mm-1cm deep

- Aspirate then slowly infiltrate. If it is difficult, you may be in the nerve or in a tendon – withdraw slightly and try again

- Inject anaesthetic (2-3mL is usually enough)

Radial nerve block:

- Palpate the radial styloid process. Your injection will be 1cm proximal and the aim is to go around the styloid process in the subcutaneous plane

- Clean the skin

- Insert the needle

- Aspirate

- Inject anaesthetic, advancing around the radial head as you go (5mL is usually enough)

Figure 11. Image demonstrating the injection site and anaesthetic field for ring blocks.

Conclusion

- Early recognition of the injury mechanism can help to guide clinicians on whether this is a flexor or extensor tendon injury and timelines for healing

- Identification of tendon rupture injuries and open injuries needs immediate referral to hand surgeons as per local protocol

- Imaging can help to define the extent of partial thickness injuries and when there is diagnostic uncertainty and the appropriate expertise. (MRI or US)

Authors:

Mr Jared McSweeney

MBChB with European Studies MRes MRCS PGCert

Core Surgical Trainee, Manchester Foundation Trust

Aadil Master

BSc MSc CSP

Specialist MSK Physiotherapist, Wrightington, Wigan and Leigh NHS Foundation Trust

Tara Williams

Medical Student, Aston University

Dr Ryan Linn

Resident Doctor, University Hospitals North Midlands X: @ryan_linn_

Dr Irfan Ahmed, Consultant in Musculoskeletal, Sport & Exercise Medicine, www.mskplaybook.com

Dr Irfan Ahmed

MBBS, MA (Cantab), MSc, FFSEM, PG cert MSK Ultrasound

Consultant in Musculoskeletal, Sport & Exercise Medicine (SEM)

www.mskplaybook.com Twitter: @ExerciseIrfan

Colin Rigney

PT, DPT, OCS, RMSK

amsku.com

References

- Gyer, G., Michael, J. and Inklebarger, J., 2018. Occupational hand injuries: a current review of the prevalence and proposed prevention strategies for physical therapists and similar healthcare professionals. Journal of integrative medicine, 16(2), pp.84-89.

- Medscape (2023) Boutonnière Deformity. Available at: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1238095-overview(Accessed: 28 August 2025).

- Boynuyogun, E., Ozdemir, D.M., Firat, T., Uzun, H. and Aksu, A.E., 2021. Combined nerve, vessel, and tendon injuries of the volar wrist: Multidisciplinary treatment and functional outcomes. Hand Surgery and Rehabilitation, 40(6), pp.729-736

- Liu, Y.J., Ding, X.H., Ji, X., Jiao, H.S., Ren, S.Q. and Zhang, H.X., 2021. Y-shaped tendon graft—a technique in the reconstruction of posttraumatic chronic boutonniere deformity. The Journal of Hand Surgery, 46(8), pp.712-e1

- Griffin, M., Hindocha, S., Jordan, D., Saleh, M. and Khan, W., 2012. Management of extensor tendon injuries. The Open Orthopaedics Journal, 6, p.36

- British Society for Surgery of the Hand (BSSH), 2025. Volar Plate Injury. Available at:https://www.bssh.ac.uk/patients/conditions/1021/volar_plate_injury [Accessed 28 August 2025]

- Beutel, B.G. and Waseem, M., 2025. Mallet finger injuries. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing

- Abrego, M.O. and Shamrock, A.G., 2019. Jersey finger.

- Beutel, B.G., Gutowski, K.S. and Marappa-Ganeshan, R., 2024. Hand Extensor Tendon Lacerations. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.